OSX/MacRansom

› analyzing the latest ransomware to target macs

6/12/2017

love these blog posts? support my tools & writing on patreon! Mahalo :)

Want to play along? I've shared both the malware's binary executable ('macRansom'), which can be downloaded here (password: infect3d).

Please don't infect yourself!

Please don't infect yourself!

Background

Happy Monday! Today we've got some new macOS ransomware to blog about :)

Discovered by Fortinet researchers, the malware was originally discussed a posting titled "MacRansom: Offered as Ransomware as a Service" (by Rommel Joven (@rommeljoven17), and Wayne Chin Yick Low (@x9090). Go read their great report first...then come back here!

Now, as I'm supposed to be working on the white paper for my VirusBulletin 2017 talk let's cut to the chase and jump right in, as time is of the essence.

Analysis

OSX/MacRansom is rather lame piece of ransomware. It's not particularly advanced from a technical point of view. However, what makes it interesting is that it targets macOS and that it's offered 'as a service.' Honestly I'm not 100% sure what the latter means - but Fortinet mentions a TOR-based web portal and contacting the author (via email) in order to customize the malware. I guess that's the service the malware author provides?

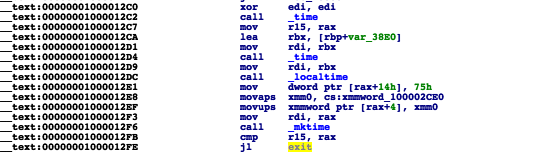

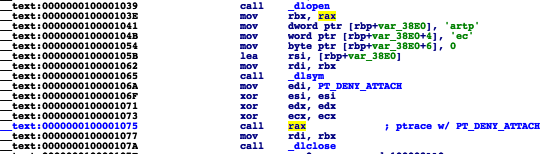

Anyways, on to the technical details! When the malware runs (as noted in the Fortinet writeup) the malware performs various anti-debugging and anti-VM checks. All are basic and trivial to pass:

-

The anti-debugging check occurs at address 0000000100001075. This is a done via call to ptrace with the 'PT_DENY_ATTACH' flag.

This anti-debugging logic is well-known (we discussed it our last blog), and it's even documented in Apple's man page for ptrace:man ptrace

PTRACE(2)

NAME

ptrace -- process tracing and debugging

...

PT_DENY_ATTACH

This request is the other operation used by the traced process; it allows a process that

is not currently being traced to deny future traces by its parent. All other arguments

are ignored. If the process is currently being traced, it will exit with the exit status

of ENOTSUP; otherwise, it sets a flag that denies future traces. An attempt by the parent

to trace a process which has set this flag will result in a segmentation violation in

the parent.

In short, PT_DENY_ATTACH (0x1F), once executed prevents a user-mode debugger from attaching to the process. However, since lldb is already attached to the process (thanks to the --waitfor argument),we can neatly sidestep this. How? Set a breakpoint on pthread then simply execute a 'thread return' command.

This tells the debugger to stop executing the code within the function and execute a return command to 'exit' to the caller. Neat!

* thread #1, queue = 'com.apple.main-thread', stop reason = breakpoint 1.1

frame #0: 0x00007fffad499d80 libsystem_kernel.dylib`__ptrace

(lldb) thread return

With the anti-debugging logic out of the way, we can debug to our heart's content!

-

The first anti-VM check occurs at 0x00000001000010BB.

After decoding a string (string decoding routine at: 0x0000000100001F30), the code invokes system to execute it, and exits if it returns a non-zero value. Specifically it executes 'sysctl hw.model|grep Mac > /dev/null':

(lldb) x/s $rdi

0x100200060: "sysctl hw.model|grep Mac > /dev/null"

(lldb) n

Process 7148 stopped

* thread #1, queue = 'com.apple.main-thread', stop reason = instruction step over

frame #0: 0x00000001000010bb macRansom`___lldb_unnamed_symbol1$$macRansom

-> 0x1000010bb <+203>: callq 0x1000028fe ; symbol stub for: system

0x1000010c0 <+208>: testl %eax, %eax

0x1000010c2 <+210>: jne 0x100001b05 ; <+2837>

0x1000010c8 <+216>: movaps 0x19f1(%rip), %xmm0

In a virtual machine (VM) will return a non-zero value, as the value for hw.model will be something like 'VMware7,1':

On native hardware:$ sysctl hw.model

hw.model: MacBookAir7,2

On virtualized hardware (i.e. in a VM):$ sysctl hw.model

hw.model: VMware7,1

To bypass this (in a debugger), step over the call to system, then just set RAX to zero:(lldb) reg write $rax 0

(lldb) reg read

General Purpose Registers:

rax = 0x0000000000000000

rbx = 0xfffffffffffffffe

rcx = 0x0000010000000100

This will trick the malware so it continues to execute, as opposed to exiting. -

The next anti-VM check occurs at 0x0000000100001126. Again, the malware decodes a string, executes it via system and exits if the return value is no-zero. This check executes: 'echo $((`sysctl -n hw.logicalcpu`/`sysctl -n hw.physicalcpu`))|grep 2 > /dev/null' to check the number of CPUs. On a VM, it appears this value is not two, so the malware will just exit to 'avoid' analysis.

On native hardware:

$ sysctl -n hw.logicalcpu

4

$ sysctl -n hw.physicalcpu

2

On virtualized hardware (i.e. in a VM):$ sysctl -n hw.logicalcpu

2

$ sysctl -n hw.physicalcpu

2

Again, if the system that the malware is executing on does not have two CPUs (which a default VM likely will not) the malware will exit. To bypass (in a debugger), again step over the call to system, then just set RAX to zero.

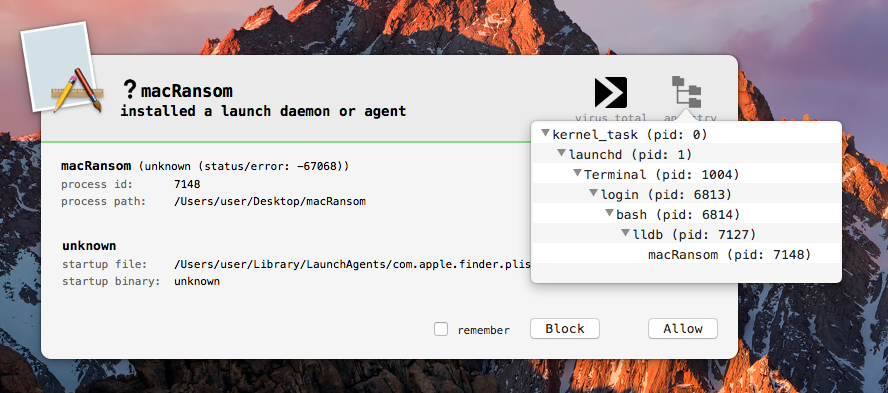

Assumining all the anti-analysis checks pass, or have been thwarted, the malware then persists itself as a launch agent. It does this by:

- Copying itself to ~/Library/.FS_Store

-

Decoding an embedded plist and writing it out to ~/Library/LaunchAgents/com.apple.finder.plist:

cat ~/Library/LaunchAgents/com.apple.finder.plist

<plist version="1.0">

<dict>

<key>Label</key>

<string>com.apple.finder</string>

<key>StartInterval</key>

<integer>120</integer>

<key>RunAtLoad</key>

<true/>

<key>ProgramArguments</key>

<array>

<string>bash</string>

<string>-c</string>

<string>! pgrep -x .FS_Store && ~/Library/.FS_Store</string>

</array>

</dict>

</plist>

Lucky for Objective-See users, BlockBlock will alert you about this persistent attempt:

As the malware first attempts to persist before encrypting any files, clicking 'Block' on the BlockBlock alert will stop the malware before it's done any damage :)

For the sake of analysis, if we allow the malware to persist itself, it will launch the copy of itself that it has just persisted (~/Library/.FS_Store) via:

launchctl load ~/Library/LaunchAgents/com.apple.finder.plist:

Process 7148 stopped

* thread #1, queue = 'com.apple.main-thread', stop reason = instruction step over

frame #0: 0x0000000100001ec6 macRansom`___lldb_unnamed_symbol1$$macRansom + 3798

-> 0x100001ec6 <+3798>: callq 0x1000028fe ; symbol stub for: system

0x100001ecb <+3803>: movb $0x25, -0x4733(%rbp)

0x100001ed2 <+3810>: movb $0x73, -0x4732(%rbp)

0x100001ed9 <+3817>: movb $0x0, -0x4731(%rbp)

(lldb) x/s $rdi

0x7fff5fbfb960: "launchctl load /Users/user/Library/LaunchAgents/com.apple.finder.plist"

* thread #1, queue = 'com.apple.main-thread', stop reason = instruction step over

frame #0: 0x0000000100001ec6 macRansom`___lldb_unnamed_symbol1$$macRansom + 3798

-> 0x100001ec6 <+3798>: callq 0x1000028fe ; symbol stub for: system

0x100001ecb <+3803>: movb $0x25, -0x4733(%rbp)

0x100001ed2 <+3810>: movb $0x73, -0x4732(%rbp)

0x100001ed9 <+3817>: movb $0x0, -0x4731(%rbp)

(lldb) x/s $rdi

0x7fff5fbfb960: "launchctl load /Users/user/Library/LaunchAgents/com.apple.finder.plist"

The orignal instance of the malware then exits, as the persistent copy is now off an running.

To continue analysis by debugging the persistent copy of the malware, execute the following in a secondary debugger window, before the original instance of the malware has launched the persistent copy (~/Library/.FS_Store):

$ sudo lldb

(lldb) process attach --name .FS_Store --waitfor

This will cause the debugger to automatically attach to the persistent copy of the malware once its launched:

$ sudo lldb

(lldb) process attach --name .FS_Store --waitfor

Process 7280 stopped

* thread #1, stop reason = signal SIGSTOP

frame #0: 0x000000011140e000 dyld`_dyld_start

-> 0x11140e000 <+0>: popq %rdi

0x11140e001 <+1>: pushq $0x0

0x11140e003 <+3>: movq %rsp, %rbp

0x11140e006 <+6>: andq $-0x10, %rsp

Executable module set to "/Users/user/Library/.FS_Store".

Architecture set to: x86_64h-apple-macosx.

Process 7280 stopped

* thread #1, stop reason = signal SIGSTOP

frame #0: 0x000000011140e000 dyld`_dyld_start

-> 0x11140e000 <+0>: popq %rdi

0x11140e001 <+1>: pushq $0x0

0x11140e003 <+3>: movq %rsp, %rbp

0x11140e006 <+6>: andq $-0x10, %rsp

Executable module set to "/Users/user/Library/.FS_Store".

Architecture set to: x86_64h-apple-macosx.

As the persistent copy of the malware is, well, a copy, it executes the same anti-debugging and anti-VM logic. Then since it running in persistent state, it checks to see if it's hit a 'trigger' date. That is, it checks if the current time is past a hard-coded value. According to the Fortinet report, this is set by the malware author (part of the 'ransomware as a service'). If the current time is before this date, the malware will not encrypt (ransom) any files, and instead will exit:

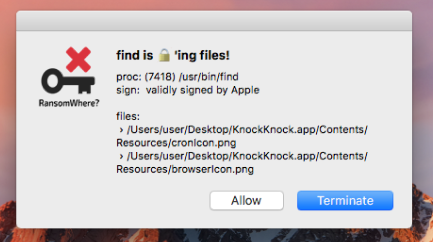

However, if the trigger date has been hit, ransoming commences! Specifically at address 0x000000010b4eb5f5, the malware executes the following, via system to begin encrypting the user's files:

(lldb)

Process 7280 stopped

* thread #1, queue = 'com.apple.main-thread', stop reason = instruction step over

frame #0: 0x000000010b4eb5f5 .FS_Store`___lldb_unnamed_symbol1$$.FS_Store + 1541

-> 0x10b4eb5f5 <+1541>: callq 0x10b4ec8fe ; symbol stub for: system

0x10b4eb5fa <+1546>: movaps 0x151f(%rip), %xmm0

0x10b4eb601 <+1553>: movaps %xmm0, -0x850(%rbp)

0x10b4eb608 <+1560>: movb $0x0, -0x840(%rbp)

(lldb) x/s $rdi

0x7fff547123e0: "find /Volumes ~ ! -path "/Users/user/Library/.FS_Store" -type f -size +8c -user `whoami` -perm -u=r -exec "/Users/user/Library/.FS_Store" {} +"

Process 7280 stopped

* thread #1, queue = 'com.apple.main-thread', stop reason = instruction step over

frame #0: 0x000000010b4eb5f5 .FS_Store`___lldb_unnamed_symbol1$$.FS_Store + 1541

-> 0x10b4eb5f5 <+1541>: callq 0x10b4ec8fe ; symbol stub for: system

0x10b4eb5fa <+1546>: movaps 0x151f(%rip), %xmm0

0x10b4eb601 <+1553>: movaps %xmm0, -0x850(%rbp)

0x10b4eb608 <+1560>: movb $0x0, -0x840(%rbp)

(lldb) x/s $rdi

0x7fff547123e0: "find /Volumes ~ ! -path "/Users/user/Library/.FS_Store" -type f -size +8c -user `whoami` -perm -u=r -exec "/Users/user/Library/.FS_Store" {} +"

What does this command do?

find /Volumes ~ ! -path "/Users/user/Library/.FS_Store" -type f -size +8c -user `whoami` -perm -u=r -exec "/Users/user/Library/.FS_Store" {} +

First, returns a list of user files that are readable and bigger than 8 bytes. Then these files will be passed (to a new instance) of the malware, in order to be encrypted! We can observe this encryption via a utility such as fs_usage:

access (_W__) /Users/user/Desktop/pleaseDontEncryptMe.txt

open F=50 (RW____) /Users/user/Desktop/pleaseDontEncryptMe.txt

WrData[AT1] D=0x018906a8 /Users/user/Desktop/pleaseDontEncryptMe.txt

open F=50 (RW____) /Users/user/Desktop/pleaseDontEncryptMe.txt

WrData[AT1] D=0x018906a8 /Users/user/Desktop/pleaseDontEncryptMe.txt

The actual encryption routine of the malware begins at 0x0000000100002160. This function is invoked indirectly via a call to 'pthread_create()':

As noted by Fortinet, the encryption is not some RSA-based scheme, but rather uses a symmetric cryptographic algorithm. Unfortunately (for users) though there is a static key (0x39A622DDB50B49E9), Joven and Chin Yick Low state that for each file the key is "permuted with a random generated number." Moreover, this random permutation is not saved nor conveyed to the attacker. Thus it appears that once encrypted, the files are pretty much gone for good (save for a perhaps a brute force decryption attack).

Good news, RansomWhere? can generically detect at block this attack:

Astute readers might wonder why the alert displays 'find' as the process responsible for the encryption (vs. the malware's .FS_Store). The reason is, 'find' invokes fork()' then 'execvp()' to execute the command that is specified via '-exec' option. RansomWhere? uses the OpenBSM auditing capabilities of macOS to track process creations - and while such auditing generates process events for fork(), exec() and execve(), it does not (AFAIK) support execvp(). As such, while the fork() process event it detected (and the path set to /usr/bin/find), the subsequent execvp() call is not audited. Thus the path stays as /usr/bin/find :/

One work around would be for RansomWhere? to re-query the OS later, say whenever it detects the creation of an encrypted file. At this point, the process (i.e 'find') will have execvp()'d and thus the 'correct' path should be returned. Or Apple could just fix the auditing subsystem :P ... I mean, this is kinda an auditing bypass?! I'll file a radar, ...then pray.

Conclusions

Luckily for users macOS malware is still rather rare. However, from a technical point of view there's no reason for this. Macs are 'easy' to infect and writing a piece of code that encrypts user files is trivial.

Though unlikely, to check if you're infected, look for the following:

- a process named '.FS_Store' (that's running out of (~/Library)

- a plist file: '~/Library/LaunchAgents/com.apple.finder.plist

love these blog posts? support my tools & writing on patreon! Mahalo :)