CleanMyMac X

CleanMyMac X

|

Airo AV

Airo AV

|

The writeup was originally was posted on his personal site.

I’ve added the sample (‘OSX.TinyShell’) to our malware collection (password: infect3d)

…please don’t infect yourself!

Background

Back in 2018 I (Jaron) presented a talk titled “Macdoored” at a handful of small conferences. This talk was about various in-the-wild APT attacks I’d seen targeting Macs. In the talk I took a minute to mention the backdoor that the attackers were using - which was a modified version of Tiny SHell. This backdoor, Tiny SHell, is open source) and operates like a shady version of SSH. It’s been a while since I’ve encountered a new sample, but I fully believe attackers are still out there using it.

If you watched the “Macdoored” talk then you’ve seen what attackers are doing “post-mortem” with this tool. However, no technical details have been discussed about the malware itself. This could be because in reality it’s changed minimally from its open source form, but these modifications do allow us to detect its uniqueness in a handful of ways. Since this malware has been modified by malicious actors, calling it Tiny SHell doesn’t seem accurate. So I will refer to this specific modified version as “TinyTim” (as I started trying to write this blog post around the holidays and dragged the release out until now).

The sample used in this blog post can be found here on VirusTotal (SHA256: 8029e7b12742d67fe13fcd53953e6b03ca4fa09b1d5755f8f8289eac08366efc).

On the VirusTotal page, you’ll notice that many of the AV scanners mark this as OSX.Keydnap. I myself would like to know how this link was made, as I do not see the (any?) commonalities.

Finally, before we get started here, I’d like to give a huge shout-out to Patrick Wardle at Objective-See for his guidance on Hopper disassembler.

Initial Impressions

First observations show that this malware is signed by a developer. It’s unknown if this was a legitimate stolen signing certificate or if it was created and owned by the attacker. This is interesting because malware is generally only signed for the purpose of defeating Gatekeeper. As I mentioned in my “Macdoored” talk, this malware was dropped on the victim systems over SSH using compromised credentials. Perhaps the attacker used a signed binary on purpose in the interest of blending in (as the majority of binaries on macOS are signed). Using macOS’s codesign utility, we can dump the malware’s codesigning information:

$ codesign -dvvv "Tiny SHell/TinyTim" Executable=Tiny SHell/TinyTim Identifier=Tss Format=Mach-O thin (x86_64) CodeDirectory v=20200 size=611 flags=0x0(none) hashes=15+2 location=embedded Hash type=sha256 size=32 CandidateCDHash sha256=4ff9613d89ae2363983588f9b3f458a45741785b CandidateCDHashFull sha256=4ff9613d89ae2363983588f9b3f458a45741785b41ff30ea47566ae51120a0ad Hash choices=sha256 CMSDigest=4ff9613d89ae2363983588f9b3f458a45741785b41ff30ea47566ae51120a0ad CMSDigestType=2 CDHash=4ff9613d89ae2363983588f9b3f458a45741785b Signature size=4659 Authority=(unavailable) Info.plist=not bound TeamIdentifier=9LDYQNSK3R Sealed Resources=none Internal requirements count=1 size=188

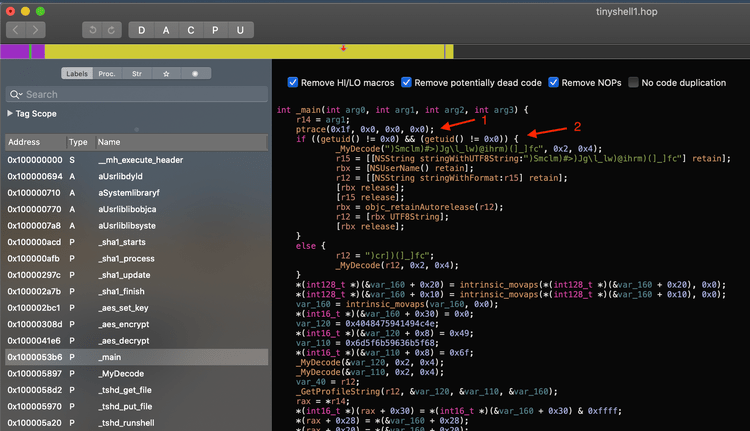

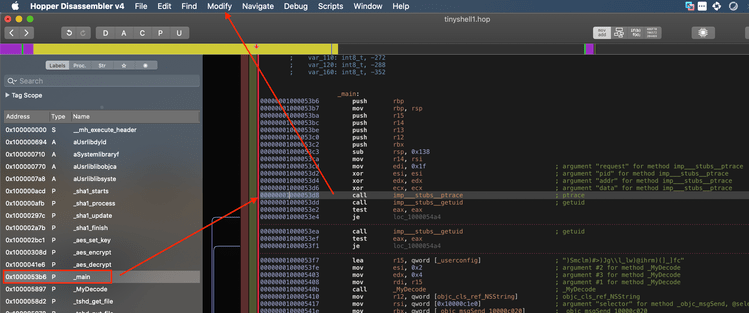

As noted, that variant we’re looking at today is (directly) based on the (open-source) Tiny SHell backdoor. One of the main changes made from the Tiny SHell source, is the addition of a function called MyDecode. This function is used by the attacker to encode some of the “sensitive” strings inside of the binary. We will have to open it in a disassembler such as Hopper if we want to get a better idea of what’s going on here.

Inside the main function, the very first check shows that TinyTim has some basic anti-debugging added to it. Right at the start we see ptrace used with the ptrace_deny_attach argument which will immediately close the program if it’s executed while attached to a debugger. We will have to keep this in mind.

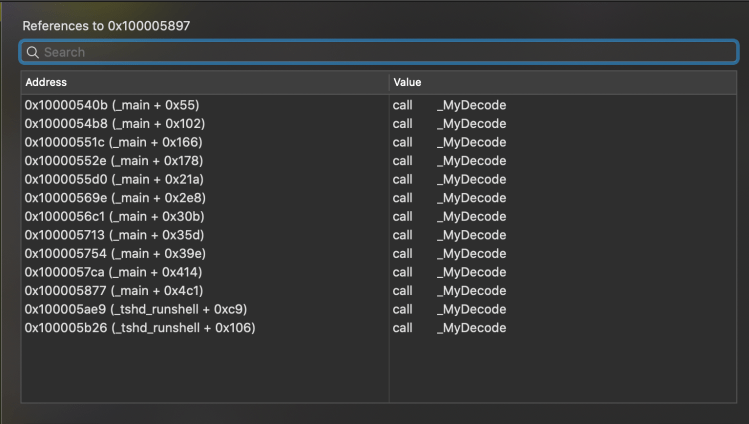

After checking for the presence of a debugger, it then invokes getuid which returns the user id of the user who executed the program. In this case, the malware is checking for a UID of 0 which belongs to the root user. In both cases, the MyDecode function ends up getting run on what looks like a garbled string. If we select _MyDecode in the labels on the left and press x we get a nice shot of all the places where this function is referenced:

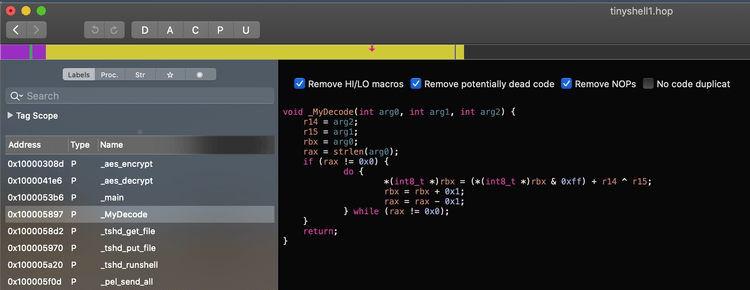

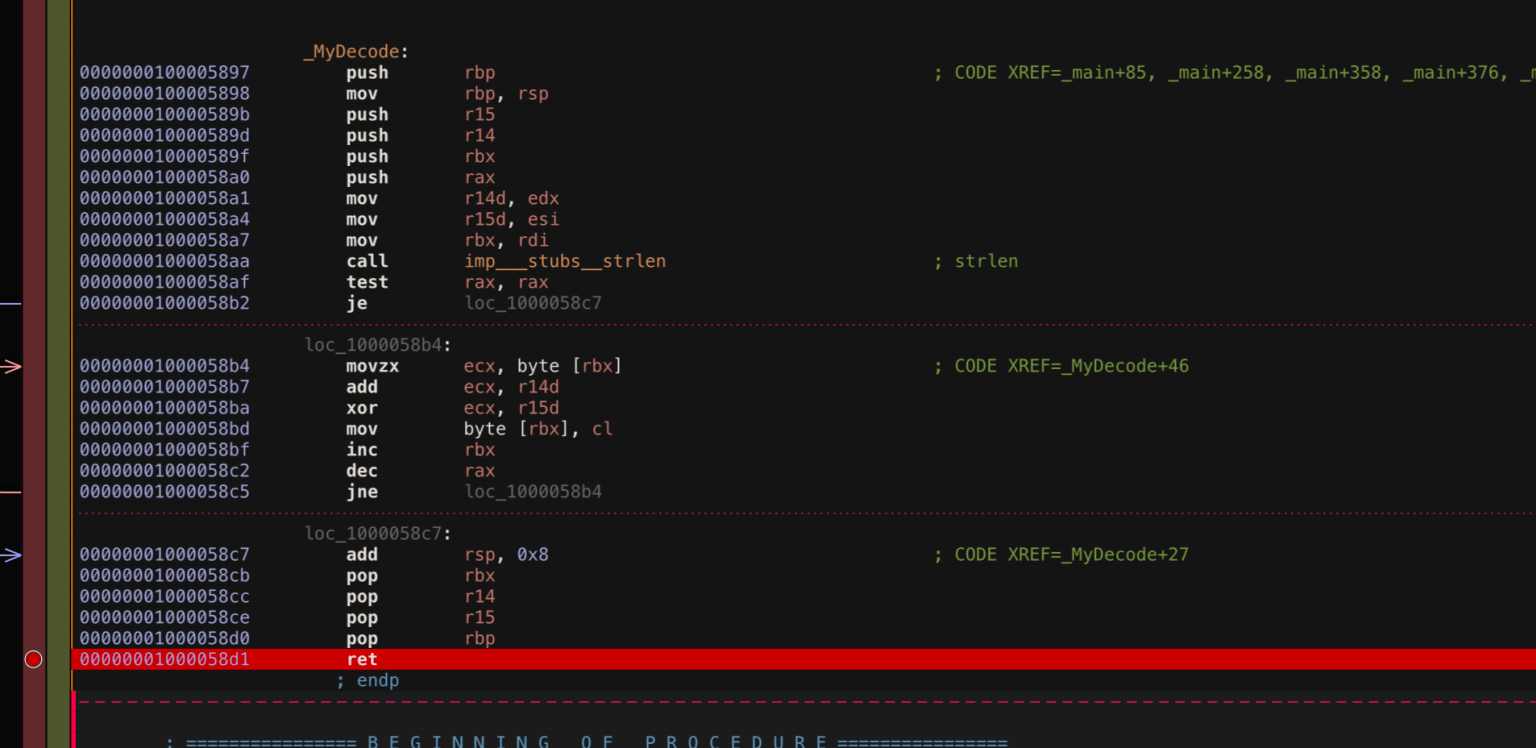

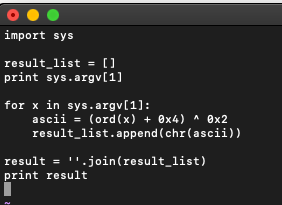

Eleven calls from main and two from tshd_runshell. Clearly this malware relies on this function frequently. If we switch the Hopper view to pseudocode we see that this function is actually quite basic:

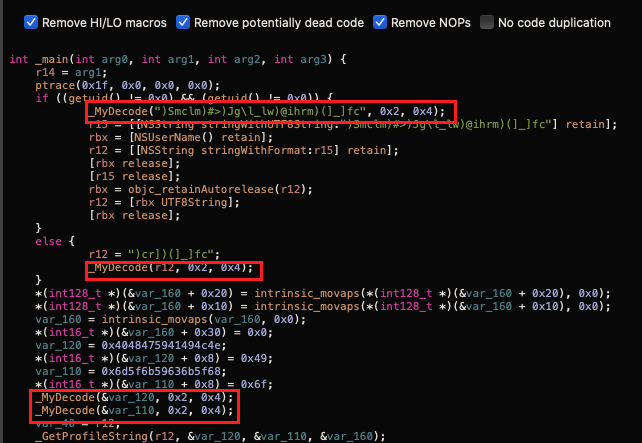

The key item to focus in on here is r14 ^ r15. This is the simple XOR’ing of two bytes which is common with malware. We see that the values of r14 and r15 are that of the second and third arguments passed to the function. The first argument being passed in here is the string that the attacker wants to unmask. If we go back to the main code we can take a look at what values the attacker passes in when he calls MyDecode:

In the first handful of calls, we see that MyDecode decodes each string using the XOR scheme 0x4 ^ 0x2. We have a few options to convert these strings back to readable text. We can either debug the program, or write a simple script to decode the strings for us. Alternatively, we can do both! Let’s start by debugging.

Prepping For Debugging

Before we begin, we have to prep this executable by taking the following steps so that it will run…

-

Give

TinyTimexecutable permissions viachmod +x -

Remove the revoked signature with:

codesign --remove-signature -

Remove the quarantine bit with

xattr -d com.apple.quarantine(assuming this malware was downloaded) -

Remove the

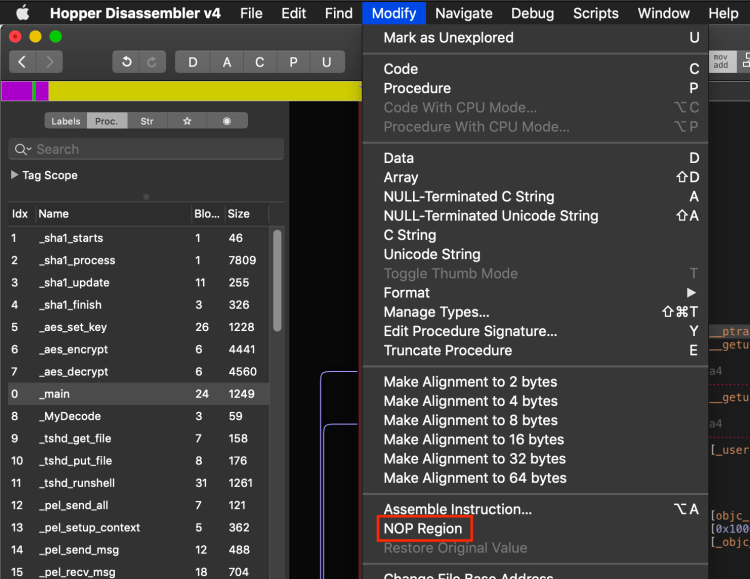

ptracecall discussed previously which is an anti-debugging technique that will close this program if the presence of a debugger is detected. We can do this by placing a breakpoint on theptracecall and then stepping over it or we can simplyNOPit so we don’t have to worry about an extra breakpoint every time we run it.

Debugging

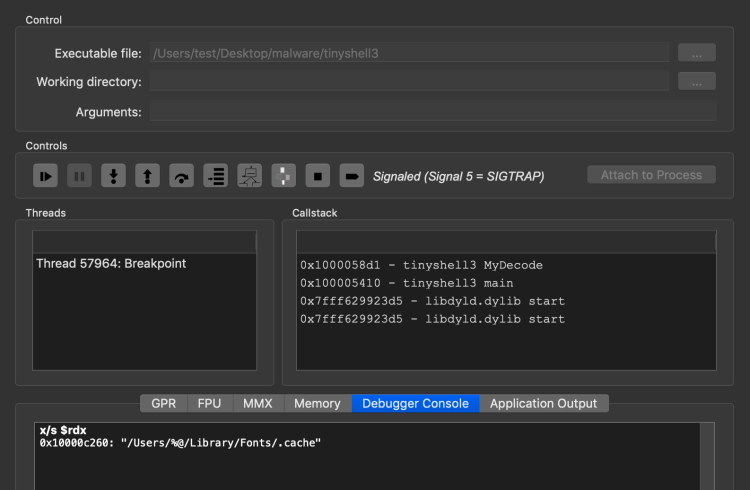

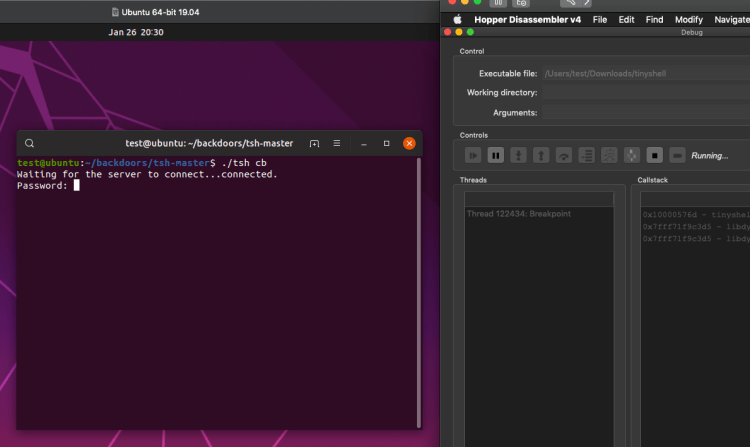

Now that we’ve gotten all the setup out of the way we can open TinyTim in our debugger and start playing with the MyDecode function. Let’s put a breakpoint on the return at the end of the function and kick off the debugger:

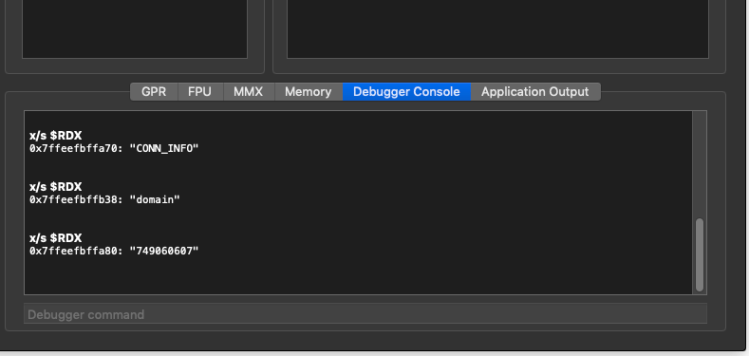

When the breakpoint is hit within the debugger it means the MyDecode function just finished running. If we print the RDX register using the x/s $rdx command we can see the string that was decoded:

In this case, we see that the decoded string is "/Users/%@/Library/Fonts/.cache". Keep in mind we are running this as a basic user and from what we saw in main, a different path would be used if it was run as root (see the if/else statement in the first screenshot). We can continue to "skip to next breakpoint" and print each string. The result is not surprising:

0x10000c260: “/Users/%@/Library/Fonts/.cache”

0x7ffeefbffa40: “PROG_INFO”

0x7ffeefbffa50: “name_masq”

0x7ffeefbffa60: “CONN_INFO”

0x7ffeefbffb28: “domain”

0x7ffeefbffa70: “”

0x7ffeefbffa70: “next_time”

Most security analysts will recognize the above strings as backdoor configuration options. Presumably, these options will have been read from the "/Users/%@/Library/Fonts/.cache" file. However, none of these configurations were successfully read as we have not created a config file at the specified location. Also notice that one of the decoded strings was empty. That’s somewhat strange, but we will revisit that later. Let’s hack together some quick python code that can unmask these strings as well because that never hurts. No rocket science here, we’ll just step over each character in a supplied string and run the XOR scheme on it to get the decoded character.

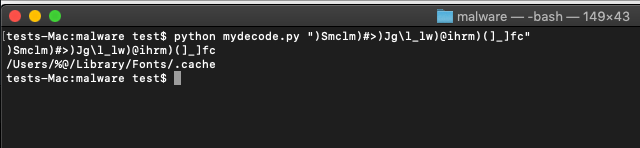

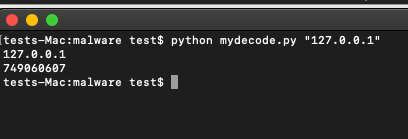

And now we can easily decode without the use of the debugger:

Awesome! We’re now able to take various strings stored in the executable and view them in plain text. Moving on, we can try to create a config file to see what happens, but we don’t know the format of said config file. Let’s see if we can figure that out.

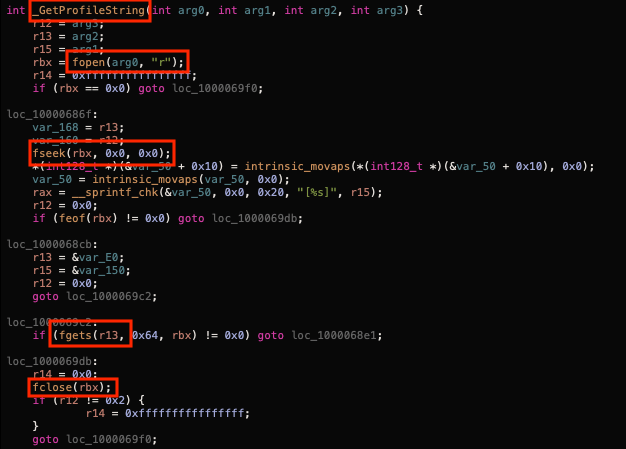

The key to discovering the config format actually lies within the getProfileString function. This function makes the only references to the fopen, fgets, fseek, and fclose functions. These are functions commonly used for opening, closing, and moving about the different contents of a file.

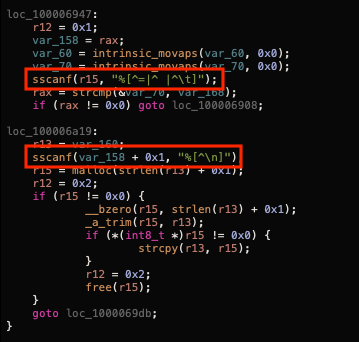

As we can see fopen opens the file specified as arg0 which in our case is the config file for the malware. It then begins parsing it. At the bottom of the file we see sscanf is being used with some specific formatting:

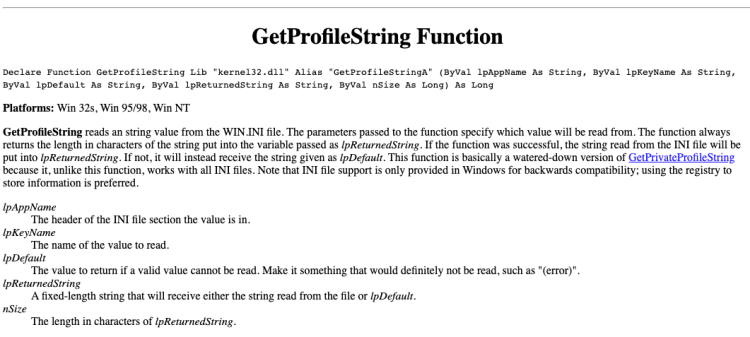

You can either Google the sscanf function to try to figure out what’s going on here (if you’re not familiar with it) OR you can do what we should have already done and just Google the GetProfileString function which reveals exactly what we’re looking for…

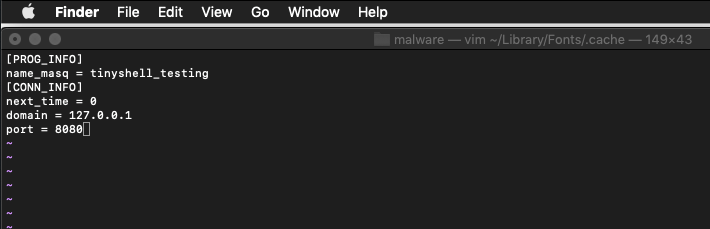

So here we have a function that is some type of port from Windows allowing users to read an ini formatted config file. This makes sense if you think about the values we saw earlier resulting from the MyDecode function. This means the items in all caps were lpAppName values and the lowercase items were the lpKeyName values. This of course feels a little unnatural on Mac since this is part of the Windows ini format, but in reality it’s nothing more than a text file and is that really a format? This means our config file should look something like the following:

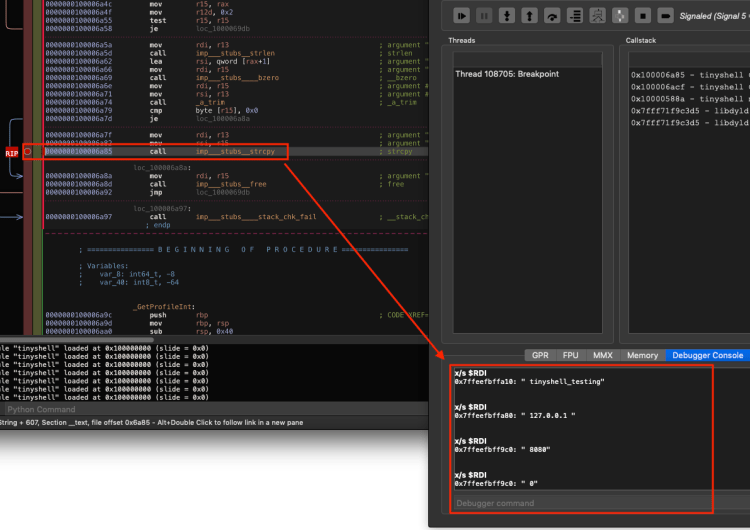

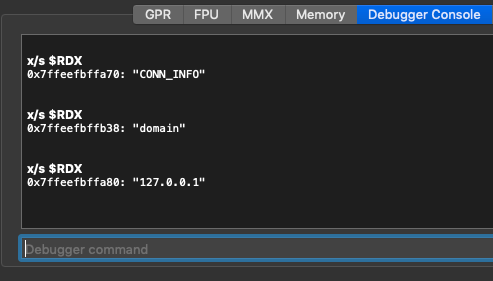

The values used here are of course made up for my own testing, but this formatting should do the trick. An easy way to confirm is to place a breakpoint on the strcpy function near the bottom of getProfileString because presumably this function is used to save the strings pulled out of the config file. Once the breakpoint is hit we can print the RDI register using x/s $RDI (RDI should almost always hold arg0 when functions are called) to display the first argument being passed to the strcpy function before continuing to the next breakpoint and repeating.

With the proper config file now formatted we are getting closer to having operational malware. However, there are still a few hang ups. Let’s revisit the breakpoint we put on the myDecode function and print out each decoded value again. If you recall, the sixth string we tried to print came out as an empty string. Let’s see if anything has changed there.

Interesting! The decoded string now turns up as 749060607. Notice that this string is decoded right after the domain string is decoded. Just by looking we can tell that it’s the same length of the localhost IP address that we supplied – 127.0.0.1.

If we use the myDecode.py script we wrote and run it on 127.0.0.1 is it possible that we get 749060607?

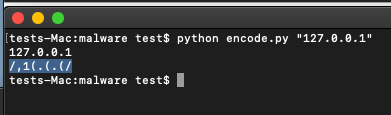

Sure enough! That seems to be the case. So as it turns out, the IP address that we use in our config file has to be encoded using the XOR scheme. This is wise on the attacker’s end. It ensures that even if the config file is found the Command and Control IP or domain isn’t discoverable in plain text. It also ensures the C2 they use can’t be picked up by a simple YARA rule if they’re using a known malicious IP address (which this particular actor did! Again, see the Macdoored video for more details). So if we want to see a successful connection from this malware we have to ensure that the IP (or domain) stored in the config file is first encoded accordingly. Since XOR is reversible and we already know the scheme being used, this ends up being quite simple. We can do it by flipping a single operator in our python myDecode script:

1ascii = (ord(x) + 0x4) ^ 0x2…to:

1ascii = (ord(x) – 0x4) ^ 0x2Which gives us 127.0.0.1 in the needed masked format which can be decoded properly after we update our config file:

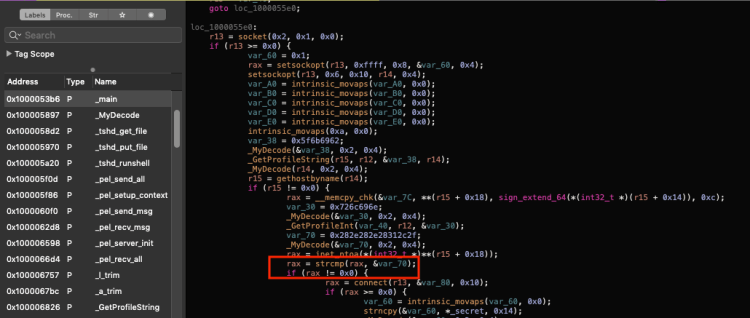

Now you’d think we would be about ready to get a connection back to our C2 server. However, TinyTim has one more anti-debugging trick up its sleeve. If we take a look at the main function again in pseudocode we’ll notice that the connect function getting called is dependent upon a non-matching string compare.

Let’s add a breakpoint on this strcmp function and see what’s being compared here by printing registers RDI and RSI (the first and second arguments passed into strcmp):

Of course. Before a connection is made to the specified C2 a check is done to ensure that this is not an attempt to connect to the same computer that is running the malware. Another smart move by the malware author. There are many ways to get around this. For simplicity I will start the Tiny SHell server inside a VM, take the local IP address of that VM, remask the IP with the XOR scheme, and add it to the config file. Problem solved. Running TinyTim will now create a connection back to my Tiny SHell server on my VM. This unveils the final hiccup.

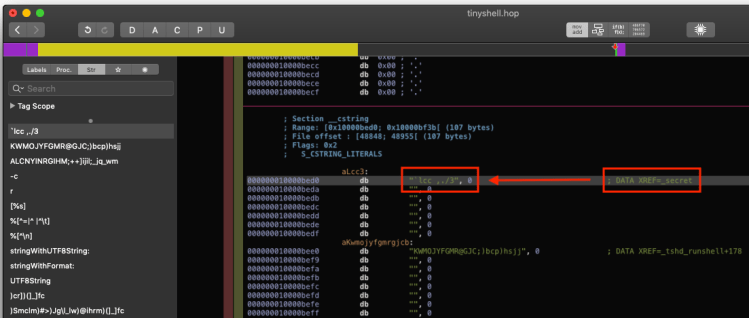

TinyTim wants a password. This is expected since in its open-source form Tiny SHell requires a user to enter their password. However, since we didn’t see a password option specified in the config file we know that it has to be stored within the executable somewhere. The open source Tiny SHell refers to the password as secret. In Hopper, we can do a simple search for secret:

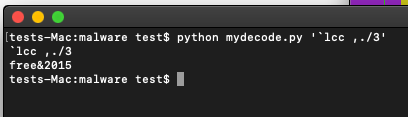

Here we see an XREF pointing to an interesting string `lcc ,./3. We can try using this as a password but the odds are probably good that this, like every other string in the executable, is actually encoded. So we will decode it first with our python script:

The password seems to be free&2015

And at last we’re in business. The goal this entire time has been to get the malware to connect to our C2 server to see if it’s further modified in any way. As it turns out, from here on out this malware behaves just like open source Tiny SHell. So the major additions were the encoded strings, the addition of a config file for quick changes, and a handful of anti-debugging techniques. Rather than continuing to use our decompiler, it makes more sense to just look at the Tiny SHell client source code.

Conclusion

In 2013 Securelist published a blog post regarding a campaign targeting Uyghur Mac users. The blog post provided solid technical detail revealing that the Mac ported sample seemed a bit less sophisticated than the one discussed above. Of course that was seven years ago and Mac security was even less of a concern than it is now. Although this malware is rare I wouldn’t be surprised if it was still being used in targeted intrusions as I’ve run into it multiple times throughout my career. The shared code is very solid ground as far as backdoors go and is easy to integrate into other projects while keeping the executable size small. If you’ve encountered this malware or have additional samples and you’re comfortable (and legally capable of) sharing, please feel free to reach out.