I’ve uploaded a sample (password: infect3d).

Background

Thanks to the amazing support of the “Friends of Objective-See” (such as Jamf and 1Password) and my amazing patrons, I recently was able to step down from my 9-5 job to focus exclusively on all things Objective-See, including:

- 🛠 Objective-See’s free, open-source tools

- 📚 The free, “The Art of Mac Malware” book series

- 👥 The community focused “Objective by the Sea” Mac security conference

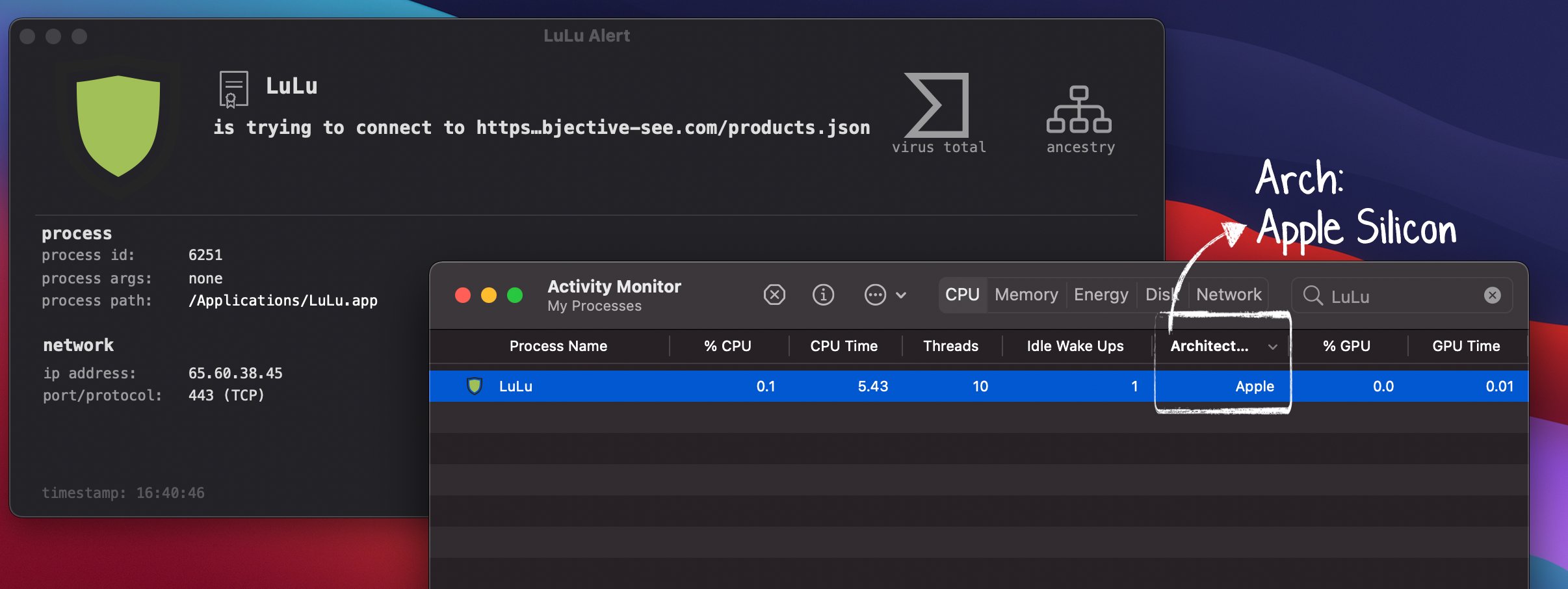

One of my main focuses has been working to (re)build all of Objective-See’s tools to run natively on Apple’s new M1 systems. For example LuLu now runs natively on Apple Silicon:

M1 (aka “Apple Silicon”) is Apple’s new (system on a) chip. As an arm-based SoC, the CPU supports an arm64 (AArch64) instruction set architecture (ISA).

Thus, in order for a binary to natively run on an M1 system (2021 MacBook Air, MacBook Pro, etc.) it must be compiled as an Mach-O 64-bit arm64 binary …which means developers must (re)compile their applications.

“But wait!” you might say, “I know can still run many older applications on my shiny new M1 system!?”. And you are correct! Apple (wisely) realized that “backwards compatibility” was essential to ensure wide-spread customer adoption of their new M1 Mac systems …and thus released Rosetta(2).

"Rosetta is a translation process that allows users to run apps that contain x86_64 instructions on Apple silicon. "

To the user, Rosetta is mostly transparent. If an executable contains only Intel instructions, macOS automatically launches Rosetta and begins the translation process. When translation finishes, the system launches the translated executable in place of the original. However, the translation process takes time, so users might perceive that translated apps launch or run more slowly at times.

The system prefers to execute an app's arm64 instructions on Apple silicon." -Apple

As noted in the quotation above, Rosetta will transparently translate x86_64 (Intel) instructions into native arm64 instruction so older applications can run (almost) seamlessly on M1 systems.

However two points to note:

- Non-

arm64code will not run natively on M1 systems (the CPU only “speaks”arm64) …it has to be translated first! - As

arm64code does not have to be translated, applications (re)compiled for M1 will run natively, and thus faster. And won’t be subject to any issues or nuances of Rosetta.

Based on the fact that native (arm64) applications run faster (as they avoid the need for runtime translation), and that Rosetta (though amazing), has a few bugs (that may prevent certain older apps from running), developers are wise to (re)compile their applications for M1!

1Process: oahd-helper [36752]

2Path: /Library/Apple/*/oahd-helper

3Identifier: oahd-helper

4Version: 203.13.2

5Code Type: ARM-64 (Native)

6Parent Process: oahd [506]

7Responsible: oahd [506]

8User ID: 441

9

10Date/Time: 2021-02-12 10:34:15.107 -1000

11OS Version: macOS 11.1 (20C69)

12

13Crashed Thread: 0 Dispatch queue: com.apple.main-thread...hence why I'm working on (re)compiling all of Objective-See's tools to natively run on M1!

Identifying Native M1 Code

As I was working on rebuilding my tools to achieve native M1 compatibility, I pondered the possibility that malware writers were also spending their time in a similar manner. At the end of the day, malware is simply software (albeit malicious), so I figured it would make sense that (eventually) we’d see malware built to execute natively on Apple new M1 systems.

Before going off hunting for native M1 malware, we need have to answer the question, “How can we determine if a program was compiled natively for M1?” Well, in short, it will contain arm64 code! OK, and how do we ascertain this?

One simple way is via the macOS’s built-in file tool (or lipo -archs). Using this tool, we can examine a binary to see if it contains compiled arm64 code.

Let’s look at Objective-See’s LuLu:

% file /Applications/LuLu.app/Contents/MacOS/LuLu LuLu.app/Contents/MacOS/LuLu: Mach-O universal binary with 2 architectures: [x86_64:Mach-O 64-bit executable x86_64] [arm64:Mach-O 64-bit executable arm64] LuLu.app/Contents/MacOS/LuLu (for architecture arm64): Mach-O 64-bit executable arm64 LuLu.app/Contents/MacOS/LuLu (for architecture x86_64): Mach-O 64-bit executable x86_64

As LuLu has been rebuilt to natively run on M1 systems, we can see it contains arm64 code ("Mach-O 64-bit executable arm64").

A binary that contains code to run on multiple architectures (e.g. Intel and Apple Silicon), is called a "Universal" or (more traditionally) a "fat" binary.

At run time, macOS will automatically select the correct (native) architecture.

On the other hand, programs that have not been (re)built for M1 systems, will not have the any arm64 code within them. For example, let’s look at BlockBlock (which I’ve yet to recompile):

% file BlockBlock.app/Contents/MacOS/BlockBlock BlockBlock.app/Contents/MacOS/BlockBlock: Mach-O 64-bit executable x86_64

As BlockBlock currently on contains Intel (x86_64) code, it will not run natively on M1 systems …and instead will have to be translated at runtime via Rosetta(2) in order to execute.

Ok, so now we know what how to identify if program has been natively build to M1 systems. Time to go hunting!

Malicious Code …now Arm’d?

Since I’m an independent macOS security researcher, I don’t have access private or proprietary malware collections or feeds. Luckily VirusTotal is generous enough to offer (free) researcher accounts. Mahalo! 🙏🏽

VirusTotal also supports a wide range of search modifiers, that will be essential in our hunt for malicious (native M1) code.

Consulting their documentation, we find several relevant search modifiers, including:

-

macho(type)

The file is aMach-O(Apple) executable. -

arm(tag)

The file containsARMcode/instructions. -

64bits(tag)

The file contains64-bitcode -

multi-arch(tag)

The file contains support for multiple architectures (i.e. its a universal/fat binary). -

signed(tag)

The file is signed.

From these we can craft a query that should give us a list of candidate files.

For example, it seems reasonable to assume that if malware authors are natively compiling code for M1 systems this code will be found within a universal/fat binary such their malicious creations will retain compatibility with older (Intel-based). As such, we leverage the “multi-arch” tag. Similarly since M1 systems will be running Big Sur which requires code to be signed, we assume the malware will be signed (and thus leverage the “signed” tag).

Of course just combining these tags will yield tens of thousands of results, as there are a ton of legitimate multi-architecture Mach-O binaries! So, let’s add another search query to look for binaries that are flagged by at least two anti-virus engines. (Yes, this will limit us to known malware, but the assumption is that as we’re looking at universal binaries, the detection will likely be due to the Intel code).

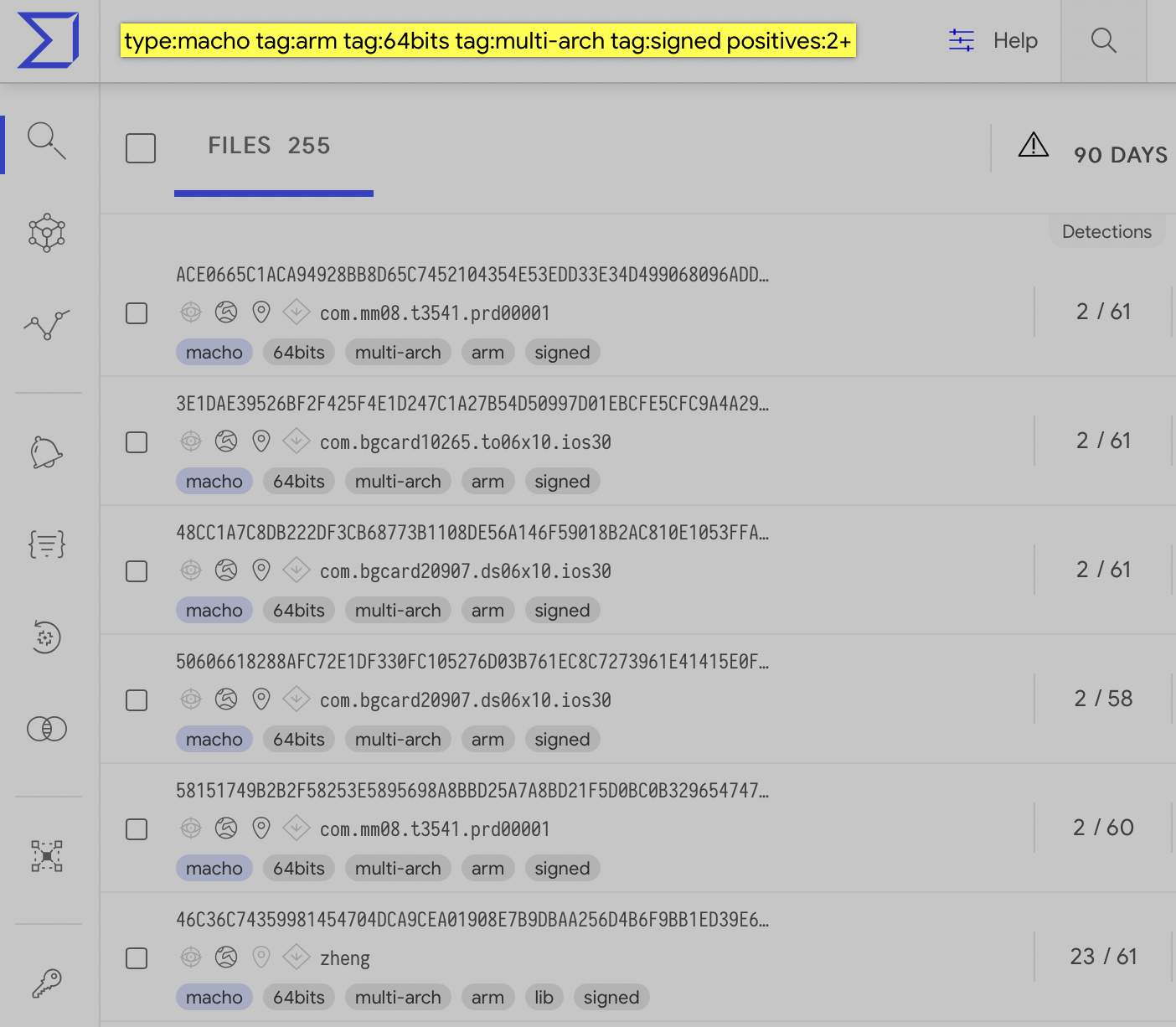

As such, our final search query is: type:macho tag:arm tag:64bits tag:multi-arch tag:signed positives:2+

…which results in 255 matches:

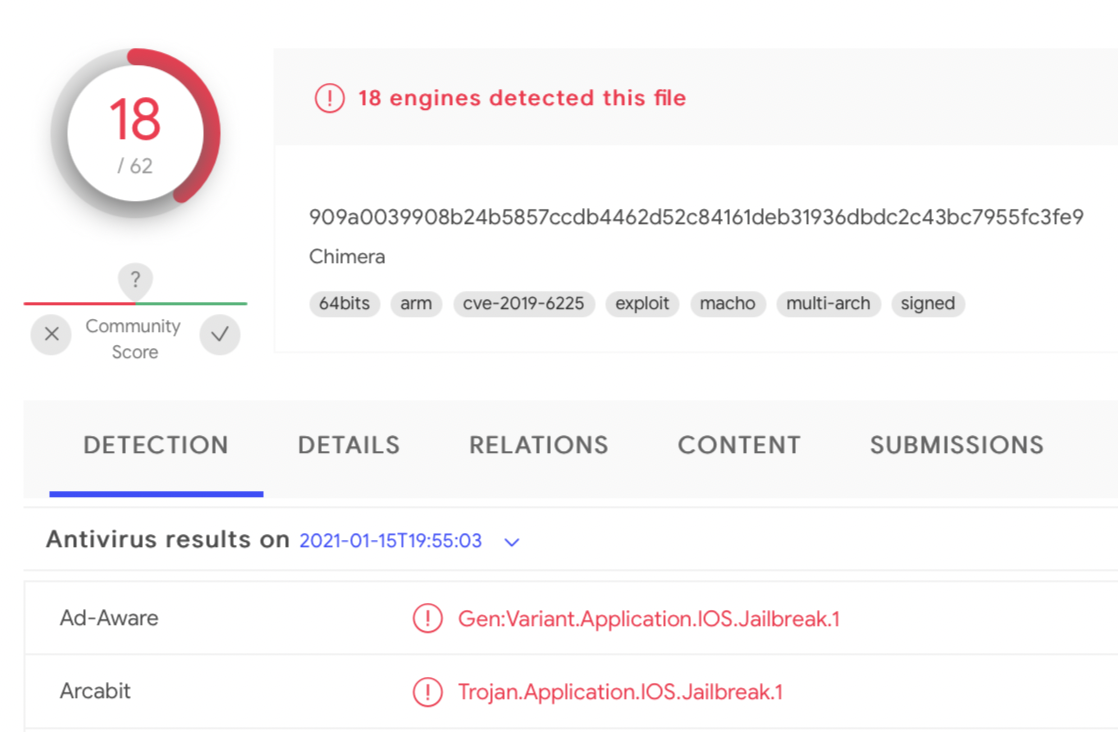

Digging thru these, many are purely iOS binaries (that true, are universal binaries, but in the sense that they are compiled to run on multiple iOS architectures e.g. armv7, armv64 …not macOS). A quick triage indicates these iOS files are largely flagged due to their relation to jailbreaks, and/or are known iOS malware:

If you have suggestion how to create a search query that ignores iOS files, I’d love to learn how!

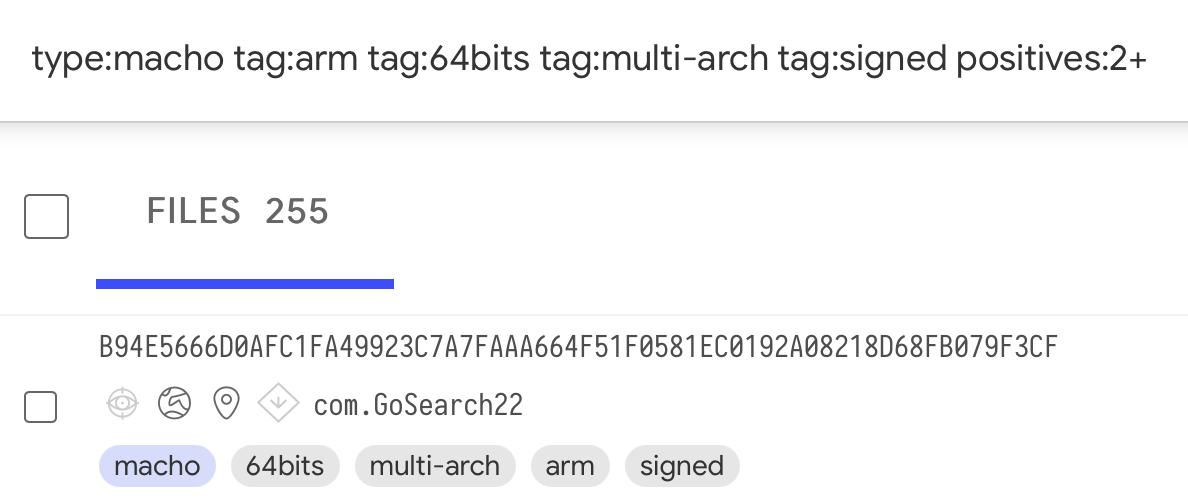

Skipping over the iOS binaries, we soon find a promising candidate, a file named GoSearch22 (SHA-256: b94e5666d0afc1fa49923c7a7faaa664f51f0581ec0192a08218d68fb079f3cf):

…is this malicious code compiled to run natively on Apple’s new M1 systems?

Triaging GoSearch22

First, let’s confirm this indeed is a macOS (vs. iOS) binary …that can run natively on M1 systems:

$ file GoSearch GoSearch: Mach-O universal binary with 2 architectures: [x86_64:Mach-O 64-bit executable x86_64] [arm64:Mach-O 64-bit executable arm64] GoSearch (for architecture x86_64): Mach-O 64-bit executable x86_64 GoSearch (for architecture arm64): Mach-O 64-bit executable arm64

So far, looks good! It’s universal (fat) Mach-O binary, that supports both Intel (x86_64) and Apple Silicon (arm64). However to be sure, let’s track down the full application bundle, and check its Info.plist file.

Thanks to VirusTotal’s ‘Relations’ logic, we can track down the binary’s parent …a full application bundle, unsurprisingly named GoSearch22.app.

First, let’s double check the standalone binary we uncovered matches the binary in the application bundle:

% shasum -a256 GoSearch22.app/Contents/MacOS/GoSearch22 b94e5666d0afc1fa49923c7a7faaa664f51f0581ec0192a08218d68fb079f3cf % shasum -a256 GoSearch/GoSearch b94e5666d0afc1fa49923c7a7faaa664f51f0581ec0192a08218d68fb079f3cf

…as expected they match. This is good news, as having a full application bundle (vs. just the application’s binary) provides a wealth of additional information.

For example in the application’s Info.plist file, we can confirm that indeed this is an application, compatible with macOS (not iOS):

% cat GoSearch/GoSearch22.app/Contents/Info.plist

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<!DOCTYPE plist PUBLIC "-//Apple//DTD PLIST 1.0//EN" "http://www.apple.com/DTDs/PropertyList-1.0.dtd">

<plist version="1.0">

<dict>

<key>CFBundleExecutable</key>

<string>GoSearch22</string>

<key>CFBundleIdentifier</key>

<string>com.GoSearch22</string>

<key>CFBundleInfoDictionaryVersion</key>

<string>6.0</string>

<key>CFBundleName</key>

<string>GoSearch22</string>

<key>CFBundlePackageType</key>

<string>APPL</string>

<key>CFBundleShortVersionString</key>

<string>1.0</string>

<key>CFBundleSupportedPlatforms</key>

<array>

<string>MacOSX</string>

</array>

<key>CFBundleVersion</key>

<string>146</string>

<key>LSMinimumSystemVersion</key>

<string>10.12</string>

<key>LSMultipleInstancesProhibited</key>

<true/>

<key>LSUIElement</key>

<true/>

<key>NSAppTransportSecurity</key>

<dict>

<key>NSAllowsArbitraryLoads</key>

<true/>

</dict>

<key>NSPrincipalClass</key>

<string>NSApplication</string>

</dict>

</plist>

…specifically note that the CFBundleSupportedPlatforms key is set to an array containing (only) MacOSX.

Hooray, so we’ve succeeding in finding a macOS program containing native M1 (arm64) code …that is detected as malicious! This confirms malware/adware authors are indeed working to ensure their malicious creations are natively compatible with Apple’s latest hardware. 🥲

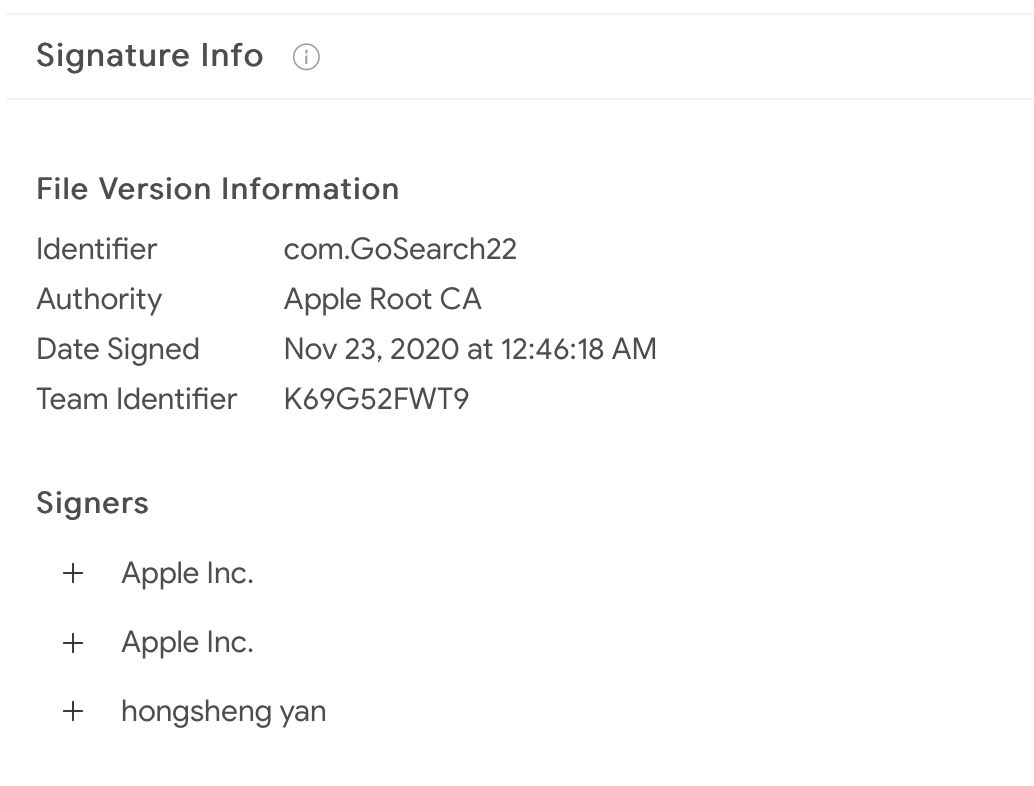

It is also important to note that GoSearch22 was indeed signed with an Apple developer ID (hongsheng yan), on November 23rd, 2020:

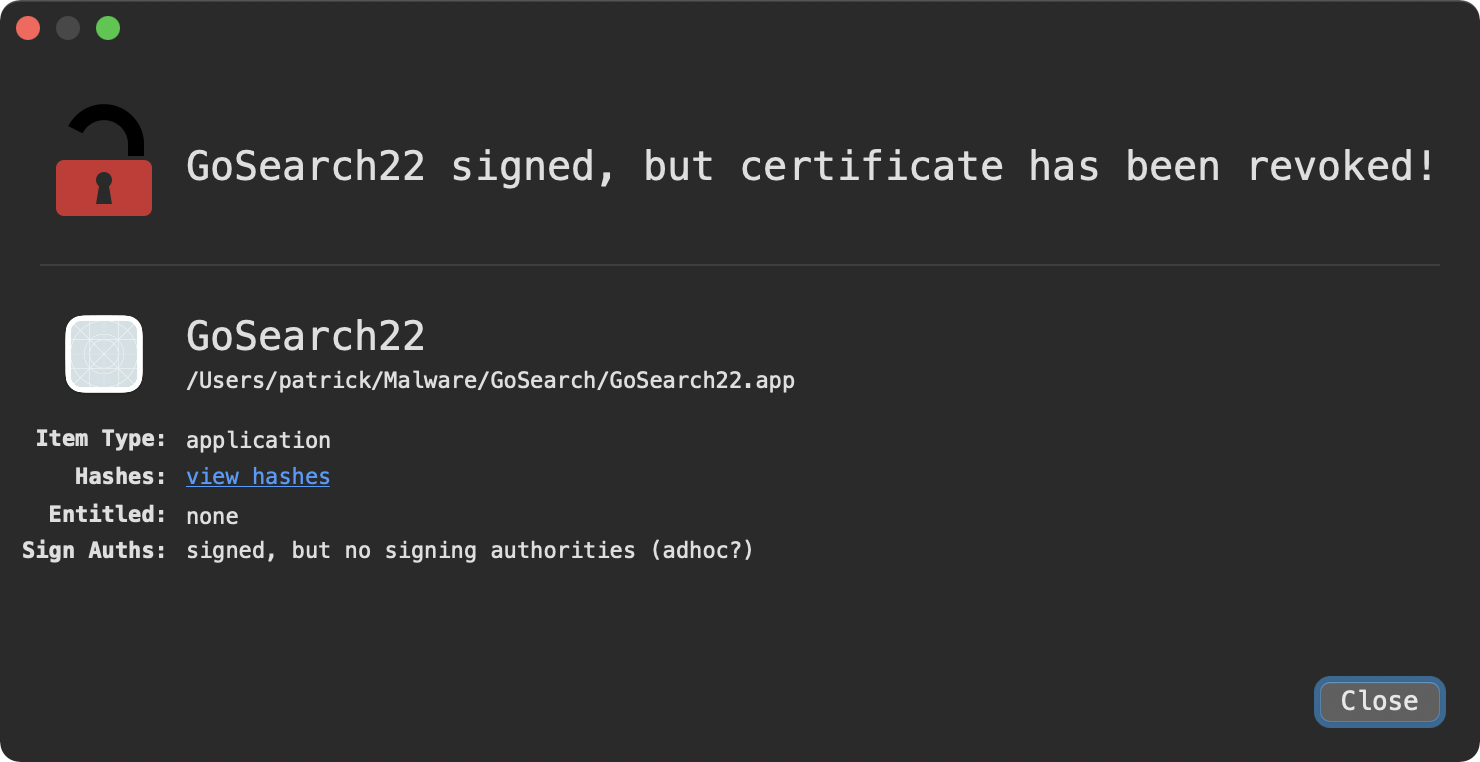

…what is not known is if Apple notarized that code. We cannot answer this question, because at this time Apple has (now) revoked the certificate:

What we do know is as this binary was detected in the wild (and submitted by a user via an Objective-See tool) …so whether it was notarized or not, macOS users were infected.

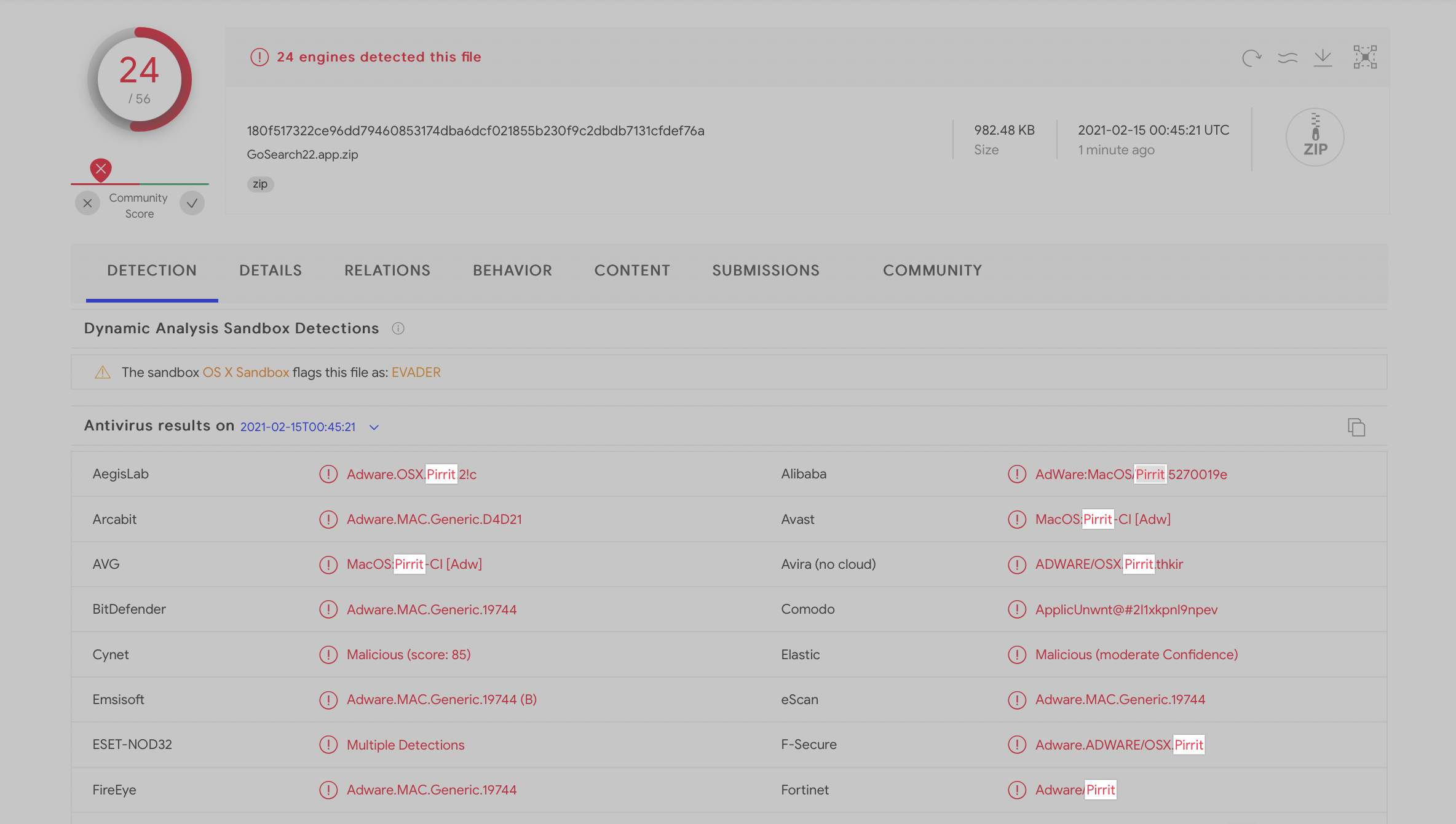

Looking at the (current) detection results (via the anti-virus engines on VirusTotal), it appears the GoSearch22.app is an instance of the prevalent, yet rather insidious, ‘Pirrit’ adware:

In a (guest) blog post in 2016, Amit Serper dove into Pirrit:

...although it should be noted that since then, it has evolved significantly.

This version/variant of Pirrit appears to:

- persist a launch agent

- install itself as a malicious Safari extension.

As this adware is rather well known, we won’t dig into it too much (today) …though we will note it implements various anti-analysis logic. For example, anti-debugging logic:

10000000100054118 movz x0, #0x1a

2000000010005411c movz x1, #0x1f

30000000100054120 movz x2, #0x0

40000000100054124 movz x3, #0x0

50000000100054128 movz x16, #0x0

6000000010005412c svc #0x80In the above arm64 disassembly, the malicious code is invoking ptrace (0x1a) via a supervisor call (SVC #0x80), with the PT_DENY_ATTACH (0x1f) flag. This attempts to prevent debugging, or if being debugged, will cause the program to terminate.

The malicious code also attempts to detect if its running in virtual machine by looking for various virtual machine “artifacts”:

# ProcessMonitor.app/Contents/MacOS/ProcessMonitor -pretty

{

"event": "ES_EVENT_TYPE_NOTIFY_EXEC",

"process": {

"name": "bash",

"path": "/bin/bash",

"arguments": ["/bin/sh", "-c", "readonly VM_LIST=\"VirtualBox\|Oracle\|VMware\|Parallels\|qemu\";is_hwmodel_vm(){ ! sysctl -n hw.model|grep \"Mac\">/dev/null;};is_ram_vm(){(($(($(sysctl -n hw.memsize)/ 1073741824))<4));};is_ped_vm(){ local -r ped=$(ioreg -rd1 -c IOPlatformExpertDevice);echo \"${ped}\"|grep -e \"board-id\" -e \"product-name\" -e \"model\"|grep -qi \"${VM_LIST}\"||echo \"${ped}\"|grep \"manufacturer\"|grep -v \"Apple\">/dev/null;};is_vendor_name_vm(){ ioreg -l|grep -e \"Manufacturer\" -e \"Vendor Name\"|grep -qi \"${VM_LIST}\";};is_hw_data_vm(){ system_profiler SPHardwareDataType 2>&1 /dev/null|grep -e \"Model Identifier\"|grep -qi \"${VM_LIST}\";};is_vm(){ is_hwmodel_vm||is_ram_vm||is_ped_vm||is_vendor_name_vm||is_hw_data_vm;};main(){ is_vm&&echo 1||echo 0;};main \"${@}\""],

...

}

}

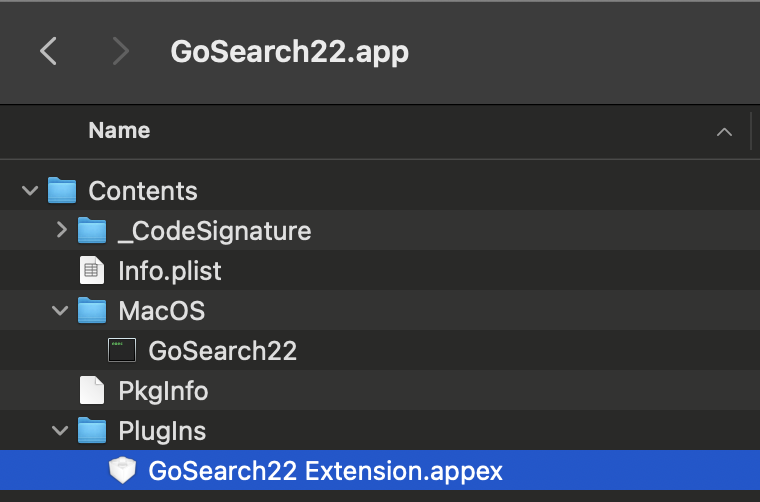

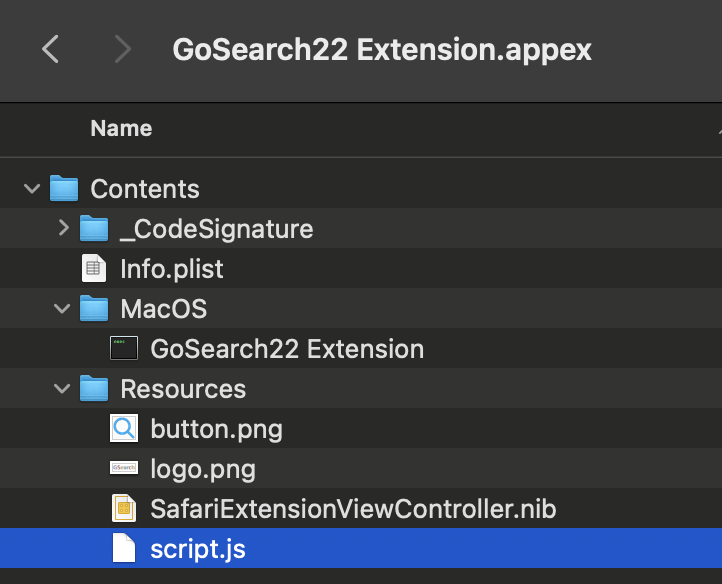

Before wrapping up this section on triaging the malicious application, let’s briefly focus on the browser extension component. First, note that application bundle contains a plugin, GoSearch22 Extension.appex:

Below is the (abridged) the Info.plist file of the plugin (GoSearch22 Extension.appex/Contents/Info.plist):

% cat "GoSearch22 Extension.appex/Contents/Info.plist"

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<!DOCTYPE plist PUBLIC "-//Apple//DTD PLIST 1.0//EN" ... >

<plist version="1.0">

<dict>

<key>CFBundleDisplayName</key>

<string>GoSearch22 Extension</string>

<key>CFBundleExecutable</key>

<string>GoSearch22 Extension</string>

<key>CFBundleIdentifier</key>

<string>com.GoSearch22.Extension</string>

...

<key>NSExtension</key>

<dict>

<key>NSExtensionPointIdentifier</key>

<string>com.apple.Safari.extension</string>

<key>NSExtensionPrincipalClass</key>

<string>SafariExtensionHandler</string>

<key>SFSafariContentScript</key>

<array>

<dict>

<key>Script</key>

<string>script.js</string>

</dict>

</array>

...

<key>SFSafariWebsiteAccess</key>

<dict>

<key>Allowed Domains</key>

<array>

<string>*</string>

</array>

<key>Level</key>

<string>All</string>

</dict>

</dict>

</dict>

</plist>

From the plugin’s Info.plist file, it’s clear it’s a Safari browser extension. And looking at the value specified by the SFSafariContentScript key, we can see its logic is contained in the script.js file:

The script is unsurprisingly heavily obfuscated:

% cat "GoSearch22 Extension.appex/Contents/Resources/script.js"

var a0a=['wr0bRjtVP8KbeFo=','LMOPwqMwNg==','wpfDqMOtw4Rtw6s=','wrpFw5rDhMOG',

'XFtr','YcOmw41Mw6U=','wqAWwrHCryXDngUnw5fCrg==','CCo/biE=','w77DhiTDsV4=',

'wpdLw4jCv8Ok','w60Ow5fDrRA=','MsOIwqYPPn7DmnzDvMO8','a8OQw5low45iw4s=',

'wrhyw5jCusK1JSdfw5dy','wr1Jw6XCpMKS','w70QGMKowrk=','w44hw4/DkjU=',

'Zgd8wrnDgw==','AMKGHHbCvw==','wqoNw4xkwoU=','w4oSFmhE','AsKoY8Or','WsOTwo/D

...

f7;}else{if(a0b('0x169','Lv[Q')===a0b('0x106','uAqz')){f6['bDFeq'](f7,0x0);}

else{var fM=document[a0b('0x210','j]sZ')];fM&&f6[a0b('0x76','2PcE')](f6[a0b(

'0x21','TrXZ')],fM[a0b('0xf3','BKpl')][a0b('0x97','uAqz')])&&window[a0b('0xd'

,'tvLM')][a0b('0x1e3','[egw')](location[a0b('0x1bc','TpDR')]);}}}catch(fN){}}

Online sources, note GoSearch22 performs standard adware-type behaviors:

"When users have apps like GoSearch22 installed on a browser and/or the operating system, they are forced to occasionally see coupons, banners, pop-up ads, surveys, and/or ads of other types. Quite often ads by apps like GoSearch22 are designed to promote dubious websites or even download and/or install unwanted apps by executing certain scripts. Moreover, adware-type apps like GoSearch22 tend to be designed to collect browsing data. For instance, details like IP addresses, addresses of visited web pages, entered search queries, geolocations, and other browsing-related information."

GoSearch22 in the Wild

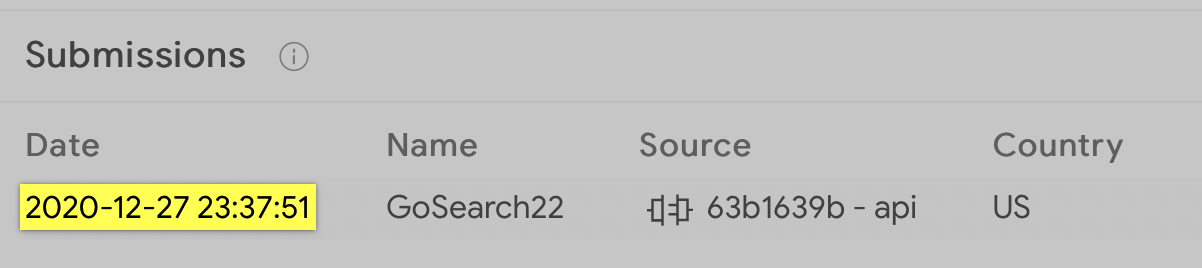

In terms of this specific (M1-native) specimen, we can see it was originally submitted to VirusTotal at the end December 2020:

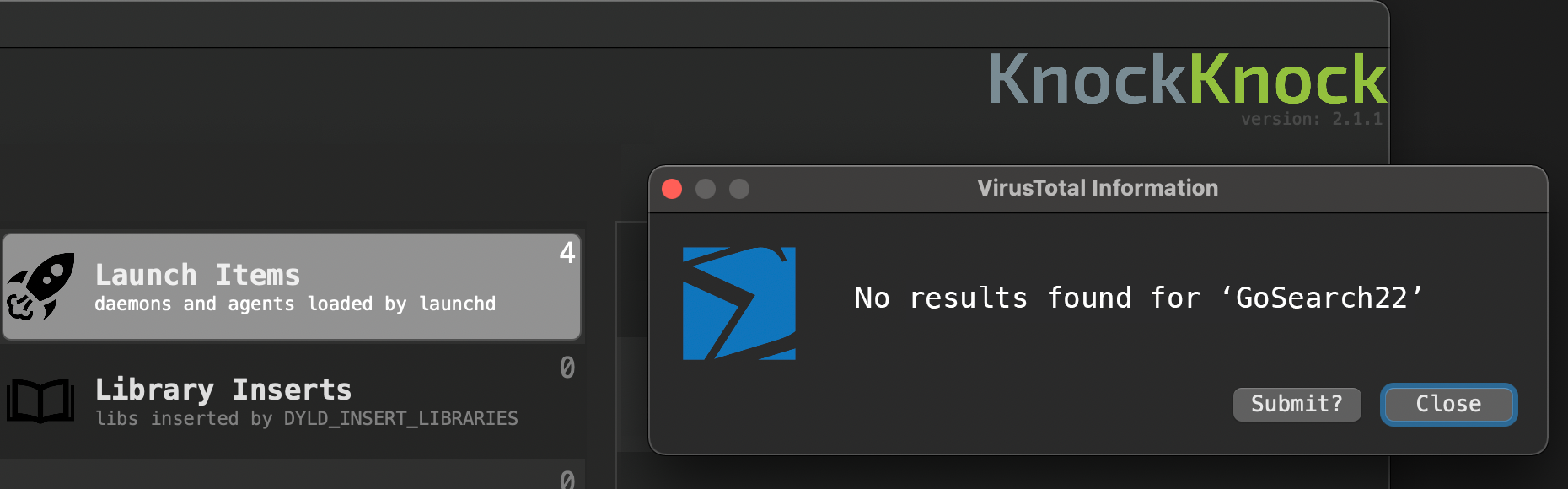

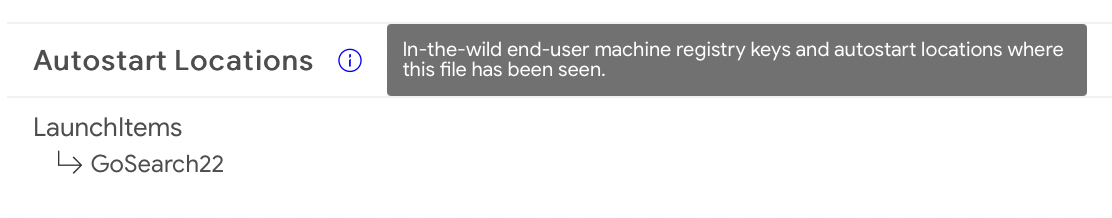

Rather awesomely, if we analyze details of the VirusTotal submission, it turns out this sample was submitted (by a user) directly through one of Objective-See’s tools (likely KnockKnock) …after the tool flagged the malicious code, due to its persistence mechanism:

Why This All Matters

Today we confirmed that malicious adversaries are indeed crafting multi-architecture applications, so that their code will natively run on M1 systems. The malicious GoSearch22 application may be the first example of such natively M1 compatible code.

The creation of such applications is notable for two main reasons.

First, (and unsurprisingly), this illustrates that malicious code continues to evolve in direct response to both hardware and software changes coming out of Cupertino. There are a myriad of benefits to natively distributing native arm64 binaries, so why would malware authors resist?

Secondly, and more worrisomely, (static) analysis tools or anti-virus engines may struggle with arm64 binaries. In a simple experiment, I separated out the x86_64 and arm64 binaries from the universal GoSearch22 binary (using macOS built-in lipo utility):

% lipo GoSearch22 -thin x86_64 -output GoSearch22_ARM64 % lipo GoSearch22 -thin arm64 -output GoSearch22_X86_64 % file ~/Desktop/GoSearch22_* GoSearch22_ARM64: Mach-O 64-bit executable x86_64 GoSearch22_X86_64: Mach-O 64-bit executable arm64

I then uploaded both (the now separated) binaries to VirusTotal and initiated scans of each. In theory both binaries would be detected at the same rate, as they both contain the same logically equivalent malicious code.

Unfortunately detections of the arm64 version dropped roughly 15% (when compared to the standalone x86_64 version).

…several industry leading AV engines (who readily detected the x86_64 version) failed to flag the malicious arm64 binary. 😢

Some AV engines that (correctly) flag both the x86_64 and arm64 binaries, however present differing names for their detections, of what logically is the same file.

For example, Trojan:MacOS/Bitrep.B vs. Trojan:Script/Wacatac.C!ml

Conclusions

Apple’s new M1 systems offer a myriad of benefits, and natively compiled arm64 code runs blazingly fast. Today, we highlighted the fact that malware authors have now joined the ranks of developers …(re)compiling their code to arm64 to gain natively binary compatibility with Apple’s latest hardware.

Specifically, we highlighted a Pirrit variant (GoSearch22.app) that was first discovered and submitted thanks to Objective-See’s free, open-source tools!

And while the x86_64 and arm64 code appears logically identical (as expected), we showed that defensive security tools may struggle to detect the arm64 binary 😥

💕 Support Us: